The Beatles sang that money can't buy you love. But it sure can prompt a lot of lawsuits -- especially if you are a Beatle. That's the finding of a new book, "Baby You're a Rich Man: Suing The Beatles For Fun & Profit." Author Stan Soocher, a University of Colorado Denver associate professor of entertainment industry, spoke with Colorado Matters host Ryan Warner.

Read An Excerpt:

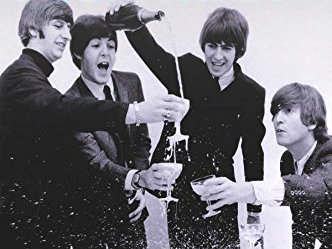

October 9, 1974, was a busy day for John Lennon. Not only was it his thirty-fourth birthday, but he was scheduled to be deposed in the lawsuit his former manager Allen Klein had brought against Lennon,George Harrison, and Ringo Starr alleging they owed Klein management commissions. Yet, Lennon spent much of Wednesday, October 9, at the Record Plant studio on West 44th Street in Manhattan,reviewing recordings he had made for Rock ’n’ Roll, a tribute album to favorite songs from his youth. “It’s something I’ve been wanting to do for years. In between takes on all sessions, Beatle days and since, we always messed around doing those sort of songs,” Lennon said. John had begun the Rock ’n’ Roll project the year before in Los Angeles with producer Phil Spector. Rock ’n’ Roll was delayed, however, after Spector seized and kept the tapes, purportedly to protect his financial investment in the studio costs for the album, then due to a car accident that Phil said had left him seriously injured. Lennon’s calls to Spector went unanswered,but Lennon got the tapes back several months later after his label, Capitol Records, paid Spector $93,000. “It was a weird day for a session,” John Lennon said about October 9. “They had a big spread or something for my birthday, and birthdays are something I try to avoid. I try to work so they won’t harass me about ‘HappyBirthday.’ But there was the spread and people coming and listening.”One unlikely guest stood out among the musicians and friends eating birthday cake and sipping champagne at the Record Plant: Morris Levy,a notorious music industry figure with reputedly extensive Mob ties. But Levy stood out in most crowds. He “had a helluva mug—big head, piercing eyes—and huge hands,” recalled former cbs Records president Walter Yetnikoff, who knew Levy well. “When he stood, he towered . . . like a mountain. His rough-hewn face was covered in a scowl. Rather than talk,he barked. His accent was guttural New York street.” During a dinner with Levy the night before, John Lennon had asked Morris to stop in at the Record Plant to hear Lennon’s versions of “AngelBaby” and “You Can’t Catch Me,” two early rock ’n’ roll songs that Levy’s Big Seven publishing company controlled. Lennon had agreed to record the Levy copyrights to settle a suit Levy filed alleging the Lennon song“Come Together,” from the Beatles’ 1969 Abbey Road album, infringed on the copyright for “You Can’t Catch Me,” written in the 1950s by ChuckBerry. John Lennon often acknowledged his musical influences, and Chuck Berry was near the top of the list. But Levy’s complaint was the first serious infringement claim against one of the Beatles. kpm, the publisher of the Glenn Miller Band’s copyrighted 1940s arrangement of the song “In the Mood,” had protested Beatles producer George Martin’s inclusion of a snippet of it in the Beatles’ 1967 recording “All You Need Is Love,” but that dispute was immediately settled with a payment to kmp that Martin said EMI ordered him to make. Morris Levy’s infringement action over “ComeTogether,” on the other hand, had serious implications for John’s reputation as a songwriter. Levy had arrived at the Record Plant midafternoon on October 9, 1974,with Phil Kahl, his music-publishing associate, and Lou Garlick, president of Ivy Hill Lithographers, which manufactured the album jackets for Levy’s record releases. At the New York recording studio, Lennon played Levy “the tracks that belonged to him and a couple more, because I was not going to say, ‘Well, now, get out, you heard your two songs.’” In fact,Levy liked what he heard so much that he believed he could gain an even greater opportunity for himself from Lennon’s recording sessions beyond John just including some Levy-owned songs on the oldies album. So Levy made sure that, during the fall of 1974, he and John Lennon would become frequent companions. For his part, Lennon said, “I was intrigued by him as a character. That’s one way of putting it.” For many in the music business, Morris Levy was difficult to avoid; he cast a wide shadow over the industry long before his legal episode with John Lennon. Born in August 1927, Levy grew up in a rough section of New York City’s Bronx borough and was sent to reform school after striking his sixth-grade teacher. As a teenager, Levy worked coat-check concessions in New York City nightclubs, where he linked up with an assortment of tough guys and mobsters, some of whom became his music-business partners later on. “I used to book talent, run concert tours in Carnegie Hall for jazz shows,” Levy said. “During the 1950s, I was involved with Alan Freed and rock ’n’ roll packages.” (Alan Freed was the pioneer rock ’n’ roll disc jockey who Levy managed and whose career was torpedoed by a congressional investigation into radio airplay payola.) Levy was also the Mob’s front man for the landmark Birdland jazz club he owned in Manhattan. In addition,he began operating music publishing firms and record labels, including Roulette Records, one of the industry’s largest independents with an artist roster that included Pearl Bailey, Count Basie, Frankie Lymon, and Dinah Washington. David Chase, creator of the hbo series The Sopranos, has said the recurring character Hesh was based at least in part on Morris Levy. Morris Levy first met John Lennon in February 1964, when the Beatles performed live on The Ed Sullivan Show from the Deauville Hotel in Miami Beach. Levy had arranged for the Beatles to use the swimming pool at his south Florida house, he said “because they couldn’t swim in the hotel that they were staying at. They would have been mobbed.” It was during another crucial juncture in John Lennon’s life that Morris Levy saw him again. When Morris attended John’s birthday party in October 1974, John was not only in the middle of the complex legal battle with the Beatles’ ex-manager Allen Klein, but he had also been separated since 1973 from his wife Yoko Ono. John was also awaiting the outcome of negotiations to resolve Paul McCartney’s 1970 suit to dissolve the Beatles’ partnership. And there was the fight against the politically driven efforts of President Richard Nixon’s administration to deport Lennon from the United States. Nixon resigned his presidency in August 1974 over the Watergate scandal, but in July the Board of Immigration Appeals had ordered Lennon to leave the country. “I had a hard year,” John Lennon said about 1974. “I was tired, period.”But Lennon would be soon be adding one more item to his list of woes: yet another lawsuit by Morris Levy. Morris Levy originally sued over “Come Together” in Manhattan federal court on April 3, 1970. Levy’s Big Seven Music filed a copyright infringement action against Beatles uk publisher Northern Songs, its US affiliate Maclen Music Inc. and the Beatles’ New York-based Apple Records Inc. (Lennon wasn’t named individually as a defendant.) Snapper Music, a publishing company Alan Freed formed to secure rights to songs in the movie Rock, Rock, Rock, had registered “You Can’t Catch Me” with the us Copyright Office in 1956. Levy bought Snapper Music from Freed. “Freed got the rights to ‘You Can’t Catch Me’ as a payola spinoff,” said Levy counsel William Krasilovsky. “Then Freed needed money desperately,so he went to his friend Morris Levy, who said, ‘I’ll buy it.’”In his song, Chuck Berry had sung, “Here come a flat-top.” When John Lennon opened “Come Together” with “Here come old flat top,” Morris Levy exclaimed, “It’s wonderful! I’ve caught the Beatles!” Levy asked Krasilovsky, who coauthored This Business of Music, the first widely read book on the subject, to pursue Big Seven’s “Come Together” infringement action. It was while working on the case that Krasilovsky first met rock ’n’roll pioneer Berry and became his lawyer for the next several decades. In Big Seven’s infringement action, Morris Levy sought the profits made from “Come Together,” plus three times the then statutory licensing royalty of two cents per song for each record sold; destruction of the Beatles’ master recording; and an injunction against continued exploitation of“Come Together.” The “Come Together” defendants responded that John Lennon’s “dynamic success with the public and with the overwhelming majority of music critics in this country should give rise to a presumption that underlying Mr. Lennon’s creativity is not a secret ability to ‘borrow’ the material of other composers.” The primary method by which a copyright plaintiff establishes infringement is by showing that a defendant’s work is “substantially similar” to the plaintiff’s. Big Seven hired several musicologists to write its experts’ reports. Harold Barlow, a songwriter, coauthor of the tomes Dictionary of Musical Themes and Dictionary of Vocal Themes, and a fixture on the expert witness circuit, prepared a note-by-note comparison of the first eight measures of Berry’s song with the first four vocal measures of Lennon’s song. Barlow found eighteen notes in common. In “Come Together,” John Lennon had sung: “Here come old flat top / He come groovin’ up slowly.” Barlow lined this up with the section in “You Can’t Catch Me” in which Chuck Berry sang: “Here come a flat-top / He was movin’ up with me.” Barlow concluded,“especially the similarities involving melody and text together, are sufficient in themselves alone . . . to make a worthy claim of infringement in this matter.” Big Seven also retained expert William Dawson, a graduate of the American Conservatory of Music in Chicago who organized the School of Music at the Tuskegee Institute of Alabama. Boasting his report was “a more accurate comparison” than Barlow’s, Dawson spotted twenty-four notes in common in the first four measures of each tune. Dawson opined that “substantially all of the melody of ‘Come Together’ is similar to the basic melodic material of ‘You Can’t Catch Me.’” He also found strong similarities between the rhythms of the two songs and the patterns of the measures. In technical terms, Dawson explained, “under emotional influence,each artist sings at one time or another the third tone of the scale one half-step lower; at other times, one will sing the flatted third as an acciaccatura;i.e., sliding up from the flatted third of the major scale to the natural third of the major scale.” After the 1970 suit was filed, Big Seven wanted to depose John Lennon. But according to William Krasilovsky, to guard their privacy when they were in New York, “John and Yoko avoided daylight. They were living in the dark. I had private detectives looking for him.” Lennon’s manager Allen Klein offered Krasilovsky a deal: “Tell your detectives to stop looking for John. I will deliver him to you on my terms. You and your wife come to my place and stay overnight. We’ll arrange for a private deposition.”“I was picked up by Klein’s car at his residence around midnight,” Krasilovsky continued, “and brought to meet with John and Yoko at the hotel they were staying at. Yoko was very militant about the situation and said that Chuck Berry should be thankful to John for putting him on the map. John Lennon’s attitude was that Berry’s music mentored him. Lennon was a compulsive fan. He had listened to the Chuck Berry record over and over again and said, ‘It must have gotten into my subconscious with that “flattop” phrase.’ We didn’t have a court reporter present. Instead, we agreed on a handshake that Lennon would sign a stipulation of what his testimony would be. We manufactured a deposition for mutual convenience.”In the brief deposition document, dated December 24, 1970, John Lennon claimed sole authorship of “Come Together,” originally intended by him as a statement on counterculture politics. But he acknowledged that“ever since I was in my teens I was acquainted with the works of Chuck Berry, whom I consider one of the original rock and roll poets.”Chuck Berry recorded “You Can’t Catch Me” in May 1955, at his first session for Chess Records in Chicago, along with three other original compositions, including his breakthrough national hit “Maybellene.” In his autobiography, Berry recalled that prior to the session, “I had created many extra verses for other people’s songs [that Berry performed in concert] and I was eager to do an entire creation of my own.” The lyrics in “You Can’t Catch Me” were based on an experience Berry had while driving on the New Jersey Turnpike, when his Buick was “overtaken by some dudes with crew cuts (flat tops) who pulled up alongside us and passed us, waving.” Berry revved up his car, which “smoking like a choo choo train” overtook the other vehicle, but he was pulled over by a state trooper and ticketed for speeding. John Lennon wasn’t sure whether Berry had “used the phrase ‘flat top’ tomean the second automobile, the driver of the second automobile or something else.” But Lennon insisted “Come Together” had “nothing whatsoever to do with an automobile.” Lennon began developing “Come Together” as a campaign song for LSD guru Timothy Leary, who glommed on to the slogan for his proposed run for governorship of California. But Leary didn’t follow through on the gubernatorial bid, so Lennon finished the song later. Lennon claimed he hadn’t heard “You Can’t Catch Me” for “approximately 10 to 11 years prior to the time I wrote my song” and not again until it was played for him at his deposition in the Big Seven case. (The Rolling Stones released a version of “You Can’t Catch Me” in 1965. Though they were close friends of the Beatles, Lennon surprisingly claimed in his December 24, 1970, deposition,“I am not familiar with the recording.”) As for Timothy Leary, Lennon said he “attacked me years later, saying I ripped him off.” In his authorized biography “Many Years From Now,” Paul McCartney admitted to intentionally copying the bass line from Chuck Berry’s recording “I’m Talking About You” for the Beatles’ “I Saw Her Standing There.” McCartney recalled that when John Lennon played his Beatles mate a draft of “Come Together,”it was “a very perky little song, and I pointed out to him that it was very similar to Chuck Berry’s ‘You Can’t Catch Me.’” But in a court affidavit,Lennon emphasized that, unlike Berry’s “You Can’t Catch Me,” the lyrics of “Come Together” were “a surrealistic stream of consciousness collection of words; to the extent they have meaning to anyone but me (and I’ve been[told] that many people don’t understand them at all), the words are meant to describe the personality and characteristics of the ‘old flat top.’”Lennon added, “When I was a youth back in the 1950’s,” a teenager with a flattop haircut “was considered the coolest of the cool. When I used the popular 1950s phrase ‘flat top’ in the first line of ‘Come Together,’ I sought to describe the coolest of the cool in 1969, as he now appeared . . . i.e., a man with hair down to his knees, with unshined shoes, doing what he pleased,one holy roller who got to be free.” Prior common source is a defense to a copyright infringement claim. So, even if Big Seven could show the phrases “Here come” and “flat top”were copyright protectable, Lennon noted that the Dick Tracy comics villain“Flat Top” and the songs “Flattop Polka” by W. Schulz and “Flat Top Pickin’” by country artist Cowboy Copas were published uses prior to either the Berry or Lennon songs. In any case, Lennon added about Abbey Road compositions, “in 1969 Paul McCartney and I wrote a song entitled ‘Sun King’ which begins ‘Here come the Sun King. Here come the Sun King.’” And there was George Harrison’s “Here Comes the Sun.” “Neither Mr. Berry nor anyone else has ever claimed that the phrase ‘Here come’ or ‘Here comes’ in those songs infringed ‘You Can’t Catch Me,’” Lennon pointed out. Though Apple Records had been named a defendant in Big Seven’s suit, Morris Levy’s counsel William Krasilovsky recalled that Paul McCartney and McCartney’s father-in-law, attorney Lee Eastman,“wanted no part of John Lennon’s mistake and stayed on the sidelines. It wasn’t a happy time for the Beatles, and Lee Eastman was nobody’s fool. To the extent that Apple was sued, Lee got a warranty, so that any damages or cost would be borne by Lennon.” The “Come Together” litigation was overseen by New York federal district judge Thomas P. Griesa, described by Rolling Stone columnist Dave Marsh as “a small, middle-aged, but boyish-looking Kennedy type who seems unimposing until you sit next to him.” Big Seven planned to call Chuck Berry as a trial witness. But Morris Levy offered to drop the suit in return for 50 percent of the income from “Come Together.” “I am calling the shots,” Levy bragged. William Krasilovsky’s settlement talks with Apple Records’ defense counsel Rosenman Colin were guided behind the scenes by abkco executive(and later John Lennon business advisor) Harold Seider. Seider had known Krasilovsky from when both worked early in their careers for well known copyright lawyer John Schulman. Seider wasn’t about to let Levy have a 50 percent stake in Lennon’s song. Instead, he instructed Rosenman Colin “to tell the Big Seven attorney to ‘stick it up his ass’; in other words no.” But on October 11, 1973, the night before the trial was to begin, the parties did agree to a settlement. “Judge Griesa had invited his wife to come to court that next morning to hear the case over the Beatles’ song,” Krasilovsky said. “I think he was angry we settled it ‘behind his back.’”Under the settlement terms, Big Seven agreed to withdraw its complaint in exchange for John Lennon’s promise that “his next album” would contain renditions of “You Can’t Catch Me” and two other Big Seven songs,which Lennon could choose. They would be “Angel Baby” by Rosie & the Originals and “Ya Ya” by Lee Dorsey, both Top 10 hits in 1961, though Lennon reserved the right to change his mind about the latter two compositions as long as he substituted two other Big Seven songs in their place. The settlement further provided that Lennon would “use his best efforts”to convince the Beatles “to license to Big Seven three songs from the Apple non-Beatle catalog currently” in print on records by Apple artists,such as Badfinger, Mary Hopkin, and James Taylor, “excluding only those songs composed by John Lennon and Yoko Ono Lennon together and those songs composed by Paul McCartney and Linda McCartney together.”If Lennon failed to get the Beatles’ approval by December 31, 1974,he promised he would record two additional songs from Levy. The Big Seven settlement made sense to Lennon because, in October 1973, he was recording his collection of rock ’n’ roll oldies in Los Angeles with producer Phil Spector and already intended to record “Angel Baby,”one of his all-time favorites. “Then I found out that [Levy] owned it. I thought, ‘Great,’” Lennon said. Lennon’s oldies project was part of an early 1970s trend, one in which artists and listeners turned back to rock ’n’ roll’s early years for reassurance following the turbulent 1960s. The Band,for example, had recorded the oldies album Moondog Matinee for Capitol Records. Before the October 12, 1973, settlement hearing before Judge Griesa was over, Northern Songs defense attorney Peter Parcher wanted it included in the court record that John Lennon agreeing to record the Big Seven songs“in no way creates any inference so far as we are concerned that any infringement was proved or can be inferred from the settlement.” |