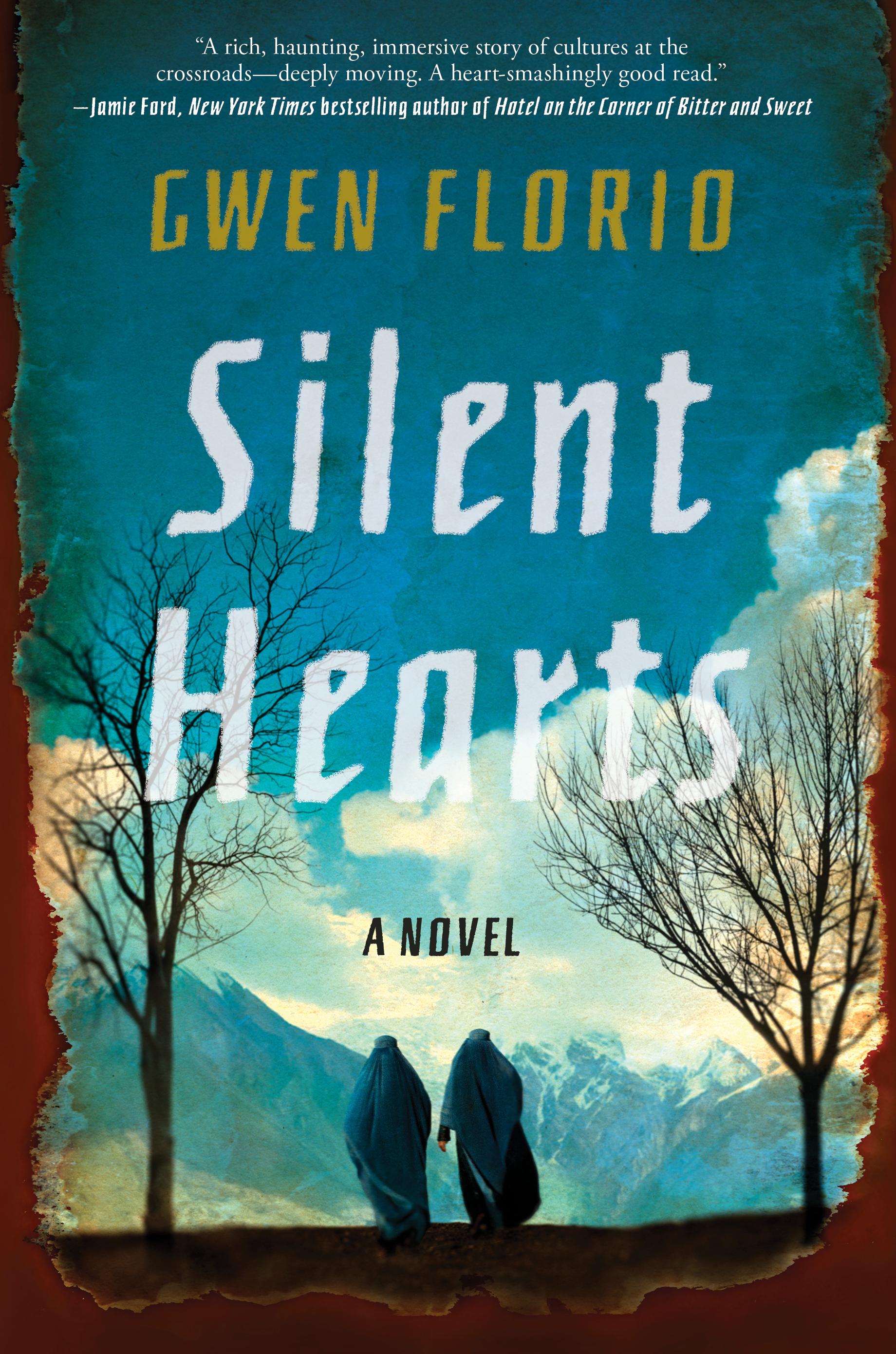

Soon after the 9/11 attacks, reporter Gwen Florio headed to Afghanistan and Pakistan with The Denver Post. Florio's experiences reporting overseas infuse her new novel, "Silent Hearts."

The book follows an American woman and a Pakistani woman working together in Kabul during the war. Florio was especially inspired by the sexism and oppression she saw toward Afghan and Pakistani women there.

The Rocky Mountain Fiction Writers recently named Florio their Writer of the Year. Today she's the city editor of the Missoulian newspaper in Montana.

Excerpt From "Silent Hearts"

Each day she remained unmarried, Farida Basra played At Least. She turned to the game as she waited for her bus on a street lined with high, bougainvillea-adorned stucco walls that shielded the homes of Islamabad’s wealthy from the envious and resentful. A woman squatted knees to chin beside her, scraping at the filthy pavement with her broom of twigs. Her skin was nearly black from long hours in the sun. Farida drew forward her dupatta, the filmy shawl-like scarf that covered her chest and shoulders. She reminded herself to be thankful. I may be poor, but at least I’m not a street sweeper. She stepped back as a family approached on a motorbike. A graybeard husband drove while his young wife clung to him from behind with one arm, cradling an infant with the other. An older child sat in front of the husband, a younger behind the wife. Dust boiled in their wake. I may still be unmarried, but at least I’m not bound to a man old enough to be my father. She nodded to a group of schoolgirls in their blue uniforms and white head scarves, and directed the game toward them. No matter what happens to you, at least your education will protect you—that was the mantra her father had taught her. He was a professor whose own professor father had made the mistake of opposing Partition from India and spent the rest of his life in unwilling atonement, opportunities snatched away, income and status dwindling apace. “But he gave me an education, and I have given you the same,” Latif Basra would tell his daughters. “It is how this family will work its way back to its rightful place. I have done my best. Now it is up to your sons.” At which Farida and her sister, Alia, would study the floor, saving their rebellious responses for whispered nighttime conversations in their bedroom. Farida let the dupatta slide back to her shoulders and held her head higher, mentally commanding the schoolgirls to see in her what she saw in herself—a professional woman, heading home from her job as an interpreter in the commercial Blue Zone, her satchel stuffed with important papers, her brain buzzing with phrases in English, German, French. Men, her own countrymen and even some foreigners, might disparage her skills and regard her work as little more than a front for prostitution. But those were old attitudes, fast being discarded in Pakistan’s cities, if not the countryside. No longer, as she told her parents nightly and to no avail, did a woman need a husband. Not in the year 2001, when so many things were possible for women. The girls rounded a corner, laughter floating behind them like the trailing ends of their head scarves. Farida tamped down envy. Old enough for some independence, still too young for the pressure of marriage, the girls had one another. Alia had departed the household for her own marriage, one that so far had produced only daughters, leaving Farida alone with her parents’ dwindling expectations. She braced herself for another evening involving a strained conversation over indifferent food prepared by a cook who also doubled as a housekeeper. Most of Farida’s inadequate salary went to her parents for household expenses and helped maintain a toehold on the fringes of respectability, even if that proximity had yet to result in a marriage for her. Her father and mother were too polite to remind Farida of how quickly she had taken to the unimagined freedoms she’d found when the family lived in England several years earlier. She was still paying for it. The fact that her work as an interpreter required constant contact with foreigners did not help her case. Despite her beauty, her parents had not been able to arrange a match with an appropriate civil servant, a teacher, or even a shopkeeper. According to her parents, these groups were the only ones who could accept her level of education along with the faint tarnish to her reputation from the time abroad. It clung to her like a cloying perfume, even after all these years. She had faced a dwindling procession of awkward second cousins and middle-aged widowers, men with strands of oily hair combed over shiny pates, men whose bellies strained at the waists of wrinkled shirts, men whose thick fingers were none too clean, men who nonetheless frowned at her with the same suspicion and aversion with which she viewed them. By now, despite her mother’s attempts to persuade her otherwise, Farida knew there was no man she could ever imagine herself loving. Even as her potential suitors drifted away—marrying other girls less beautiful, perhaps, but also less questionable—so did her friends, into arranged marriages of their own, quickly followed by the requisite production of children. Their paths diverged, and she instead hid behind her work. Farida shouldered her way from the bus and pushed open the gate to the pounded-dirt courtyard. What should she expect from her parents tonight? The silence, her parents retreating after dinner into the solace of books and music? Or more badgering? “Farida!” Her father burst out of the front door, arms spread wide. He folded her into an embrace, an intimacy he’d not permitted himself since she was a child. She extricated herself with relief and suspicion, the latter ascendant as she took in his appearance. “Is that a new suit?” He stepped back and turned in a circle, inviting her admiration for the summer-weight worsted, cut expertly to disguise his sagging stomach and spreading bum. “What do you think of your papa now?” “What happened to the old one?” A rusty black embarrassment, gone threadbare in the elbows and knees. He waved a dismissive hand. “Gone.” Sold, no doubt, to a rag merchant. Farida’s mother appeared in the doorway. She raised her arm in greeting. Wide gold bangles, newly bought, rang against one another, their hopeful notes at odds with her stricken expression. “Your father has a surprise.” Which was how Farida discovered that for the bride price of some twenty-two-carat jewelry, a knockoff designer suit, and almost certainly a newly fattened bank account, Latif Basra had betrothed his remaining daughter to the illiterate son of an Afghan strongman. “It will be a disaster.” Alia, summoned by simultaneous phone calls from her mother and her sister, stood over Farida as she sobbed facedown on her childhood bed. Alia was one of the few women in Islamabad with a driver’s license, and she used it whenever she could, which was rarely. It was after dark, dangerous for a woman to be on the road. For her to be here was a measure of her alarm. Hearing her sister’s words, Farida sat up and reached for the bookshelves, pulling out volumes at random and flinging them across the room. “What use will I have for these now?” She raised her voice so that her father, cringing in his study, could hear. She took her gauzy dupatta between her hands and tore at it. “What use have I for this? He’ll hide me away in a burqa.” She thrust at her sister a leather-bound copy of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, its title stamped in gilt. “And this! He gave me a special edition of my favorite book, to bring to my life with a man who cannot read, not even his own language, let alone English. And these hideous bangles.” She stripped them from her wrist and threw them at the wall, yelling at her hidden father, “Take these and sell them. Buy yourself another suit!” Alia kicked the bangles aside and wrestled her younger sister back onto the bed, releasing her only when Farida fell silent. “Stop. It’s done. You must decide how you’re going to deal with this.” Farida sucked in oxygen. Strands of hair clung to her damp face. Alia smoothed them back and spoke with her usual pragmatism. “Something like this was inevitable. You were never going to be permitted spinsterhood. Not with this.” She slid her hand to Farida’s chin and turned her sister toward the large mirror across the room. Even red and swollen as a pomegranate, Farida’s features—the large eyes beneath swooping brows, the imperious arch of cheekbone and nose, the full lips offset by the darling chin—commanded attention. Alia shrugged at her own reflection. “Who knew that my looks would turn out to be my best advantage?” Farida leaned against her sister, averting her gaze from the mirror. Where her own features were sharply cut, Alia’s doughy flesh was mottled and pitted, the result of adolescent acne. The same small chin that so perfectly balanced Farida’s generous mouth was a liability for Alia, nearly disappearing into the plump folds of her neck. Their father had been unable to find a wealthy man for Alia. Instead, he reacted with humiliating gratitude when she suggested to him that most unlikely and unusual of circumstances: a love match. Alia’s husband, Rehman Khan, was no less homely than she, albeit small and scrawny where she was large. “Is he a grown man, or still a boy?” their mother had wondered after meeting him. “Will she be his wife or his mother?” But like Alia, Rehman was a student of philosophy, and Farida, each time she visited them, was struck anew by their smiling, whispered conversations, more like talk between women friends than husband and wife. The two lived quietly, their lives centered on their studies and their three small girls. Farida shuddered. She had once recoiled from the prospect of such subdued domesticity. She long assumed a similar match for herself, albeit lacking, of course, the luxury of love. There would have been nightly dinners with his parents and weekend visits to her own family, those gatherings featuring tiresome eyebrow-arching gossip about the people they would inevitably know in common. Now, facing this new, terrifying reality, she yearned for that old scenario of limitations. Alia retrieved Alice from the floor and handed it to her. Farida clutched it to her chest. “If only I could be like the Cheshire Cat and disappear. If we’d stayed in London, this never would have happened.” Again, Alia splashed her with the icy bath of reality. “If we’d stayed in London, Papa would have gone bankrupt.” Far from being the shortcut to success that Latif Basra had imagined, the family’s move to London—where he’d wangled an instructor’s position at what turned out to be a second-rate college—involved a succession of increasingly dingy flats, even as his debts piled higher. “In a way, I suppose you saved him,” Alia mused. “Although who would choose that way?” “Stop.” Farida didn’t need another reminder that her own behavior had precipitated their hasty return. Those previous suitors, the ones she’d so casually rejected. How could she not have foreseen this inevitable end to her relentless faultfinding? Her parents had done her the favor of seeking out men who, if not wealthy, were at least from their own circle. She’d left her parents no choice but to opt for money. And they, perhaps wisely, had spoken for her this time. To oppose this decision would be to bring shame beyond anything she’d heaped upon them in England. “You always wanted excitement—new things, different cultures.” A filament of anger glowed within Alia’s words. Farida realized now how deeply her implied criticism of Alia’s life had cut her sister. “Now you will have them.” |