Reprinted from Full Tilt Boogie by Hal Walter, by arrangement with Out There Publishing. Copyright © 2014 by Hal Walter On a windy April day we went for a walk. Harrison’s fourth birthday was in a few days. We walked out the driveway and down the road to a gate into the neighbors’ property where I have permission to hike. When we turned around the wind was now in our faces and it seemed even stronger, peppering us with dust and sand. Harrison began to object loudly and to throw a tantrum. I picked him up and carried him on my shoulders for a short distance which calmed him down somewhat. Then my ball cap flew off my head. I had to set Harrison down in order to chase down the cap which was still rolling along the ground. Once I had retrieved it I walked back to Harrison and lifted the shrieking child onto my shoulders once more, only to have the cap blow off my head again and have to repeat the same drill. This time I tightened the fit before placing the cap back on my head. For nearly four decades I had been free, within reason of course, to curse out loud, and so with a screaming child on my shoulders when the cap flew a third time I went through considerable vocal contortions trying to keep “goddammit” from leaving my lips. Unfortunately I only managed to keep it just under my breath. I felt badly for this slip-up but hoped Harrison was more concerned with the wind than my language. Since he was prone to echolalia and did not repeat it right away, I figured it was probably OK.

The birthday presents had arrived and so when April 20th rolled around we got out the video camera and set the gifts out on the floor for Harrison to open. He went about opening the packages with gusto, ripping the paper and smiling at each one. I especially wanted to get a video of him opening the gift from my parents, and so when he started on that package I zoomed in. As the paper peeled away to reveal a big yellow tractor, he beamed with joy, looked up at the camera with a huge smile, and happily exclaimed in his own precious little voice: “Goddammit!”

***

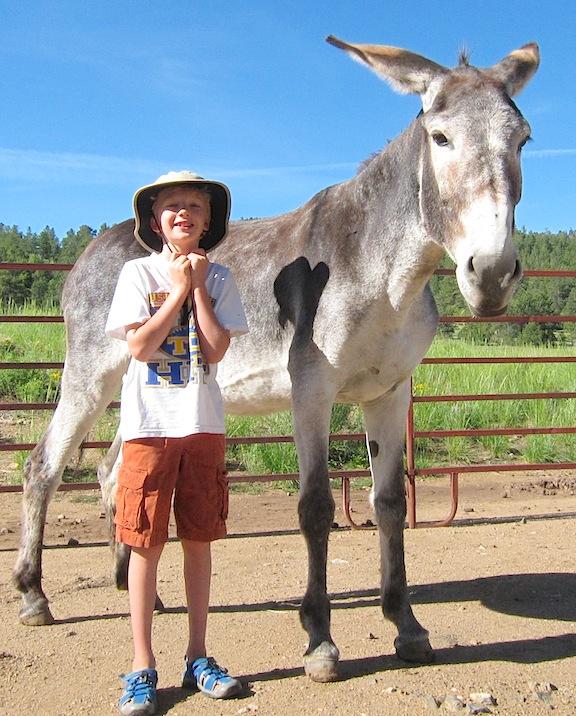

Over the years I have trained and known many burros, like myself some more and some less employable. The first burro I actually owned, Jumpin’ Jack Flash, was wild off the range and when he was finally trained to the point at which the unpredictable wildness was out of him, I missed that spirit more than I appreciated his newfound tractability. Next I had Clyde, born in captivity of wild parents. I ran all my fastest times on the pack-burro courses with Clyde, and won my first race with him. But he never had a World Championship in him despite finishing second a number of times. I trained another wild burro named Hannibal. There was a tame burro named Virgil given to me by a rancher friend. Then along came Spike, who finally won for me a World Championship, and then three more titles. I bought two burros, Billy Sundae and Ace, from breeders in New Mexico, a jack named Redbo from Curtis, and another jack named Laredo, with whom I won two more World Championships.

There were others as well and all of these burros had their own unique personalities. Some were runners out of pure joy and some were not. Some had a work ethic and others didn’t. Some reached down deep in their hearts when the going got tough and others simply gave up. There really is no stereotype with burros just as there is no stereotype with people. As I worked with more and more burros I began to appreciate their individual qualities, and to realize that we’re all here for a purpose. We’re all on our own separate journeys, and in my journey I’ve found parallels between working with burros and parenting an autistic child. For sure no burro gets up in the morning and thinks, “Dang, I think I'll run up a 13,000-foot mountain pass today.” Likewise, no autistic kid gets up in the morning and thinks, “I think I'll conform with societal norms today.” The real key to success with either burros or autistic children is extreme patience and allowing them to find their own way. Each are unique individuals and one cannot exert command over them with good results. Only when they believe something was their own idea do they truly excel.

In this regard the sport itself has become a metaphor for life for me. Success at burro racing is both preparation and then literally dealing with what the world and an unpredictable critter throws at you on race day. Rarely does everything go perfectly. Sometimes things even go quite badly. It’s how you handle what happens and go with the flow that determines success, whether that means winning or merely finishing some days. That’s how life works, too.

|