Almost everyone talks with their hands, a form of communication whose roots can be found in ancient history -- like way, way, way back. At least that's the theory proposed by Metropolitan State University of Denver archeology professor Rich Sandoval. Sandoval says sign language may go back as far as the late 700s, among the Mayan people. He spoke with Colorado Matters about his "hands-on" experience working with the ancient ruins that led to his discovery.

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity

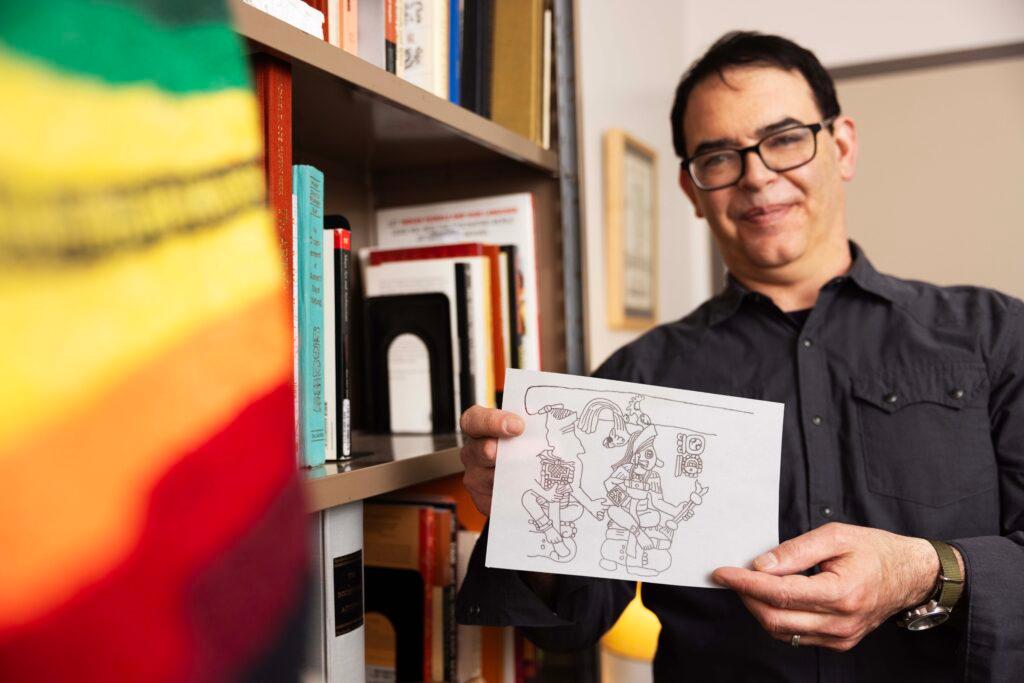

Ryan Warner: In one of these carvings, a figure has their pinky and ring finger folded in while the others remain straight out. So that's conveying something?

Rich Sandoval: Yeah. Importantly, it's not just the hand shape, it's the position of where the hands are and the orientation of the palm. So they were using all of these features to encode, so to speak, their numbers and possibly a lot more.

Warner: Okay, so it could be related to numbers.

Sandoval: It's definitely related to numbers.

Warner: Might they be conveying words?

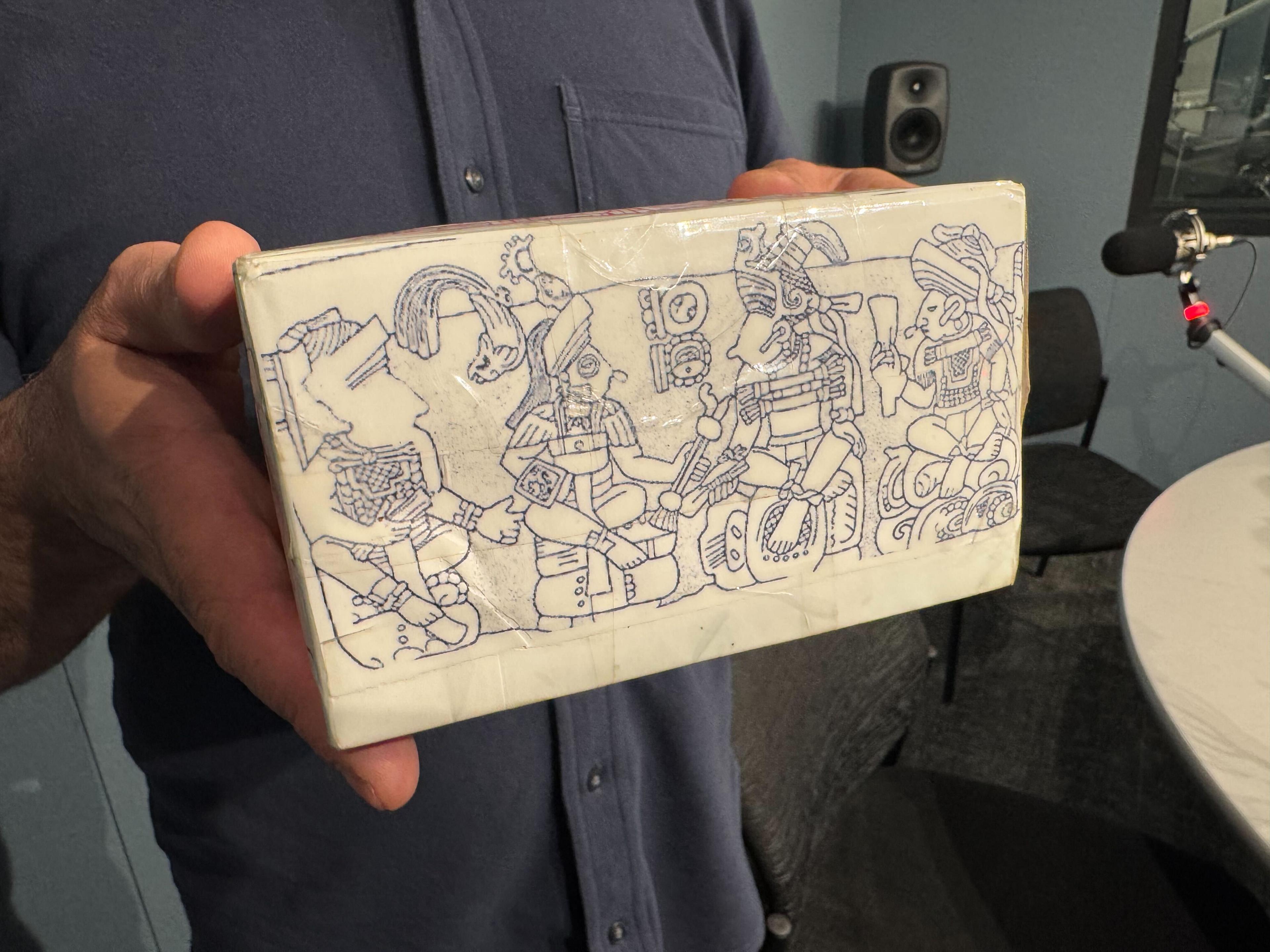

Sandoval: From what I can tell at this preliminary point, there are definitely meanings beyond numbers, but the numbers themselves are extremely important. With this monument and in my research that I focused on Altar Q, there's 16 rulers and each of the rulers is conveying a number within a date.

Warner: Okay, it's a calendar!

Sandoval: Yeah, it's a part of a complex calendar system.

Warner: And tell us about this site.

Sandoval: The site is Copán in modern-day Honduras on the border with Guatemala, and it's one of the classic Maya sites. So if you went on a tour in the classic Maya area, this might be one of the places you visit.

Warner: Now, any number of people have seen these images, and is it that they weren't paying particularly close attention to the hands? I mean, you became quite obsessed with this.

Sandoval: Yeah, I did. And that was given my background, I didn't start off working as a Maya researcher. I didn't go to any of the schools around the world that focus on the ancient Maya or anything like that. But a number of people have looked at the hands, not just on this monument and on a number of different monumental texts and some of the surviving books and murals, there's always these figures, one or more, with these very distinctive hands. And oftentimes, you'll get students or audience members in a talk asking "What's going on with the hands?" And the lecturer or whoever will say, "I'm not quite sure," or, "That is interesting. Let's move on to the next question" kind of thing.

Warner: Okay. Why don't we talk a little bit about what led you to this work, because your portal to this discovery was actually the Arapaho much closer to home. Connect those dots for us.

Sandoval: So I got a little nudge from you in 2010. You did an interview with Andy Kao, an Arapaho speaker on Andy's work at the University of Colorado on Arapaho language. He was building a conversational database, and in the interview going through his work and the Arapaho language and all the things going on, I got very interested. So I reached out to him and through the course of some conversations, I ended up changing my whole focus in graduate school. Well, Andy got me on a project looking at his conversational database, which is video of actual Arapaho speakers speaking, using the language.

Warner: And naturally, your eye maybe went to the gestures?

Sandoval: Yeah. And I never thought of myself as someone who was particularly good at visual analysis, but maybe I was, growing up around a lot of artists and stuff like that, and I was seeing these really amazing hand movements and things. And so I started looking into it and learned that they were incorporating bits of this sign language that's referred to as Plains Indian Sign Language, or just Plains Sign Language. And so this is a historical language. It was heavily documented in the 1800s. So over time, I realized these speakers were incorporating bits of that with their spoken Arapaho, and that became my dissertation focus.

Warner: Is this a way, if you are communicating in gesture as much as words? Is this a way for communities to build bridges when their languages are different?

Sandoval: So the sign language was used on its own, and it's important to note in Deaf communities, but also by non-Deaf people, and especially for the issue that you're talking about here, which was to communicate across spoken language boundaries. And some of these spoken languages were incredibly different from one another, from different language families, very complex things, but they could use this sign language as this common ground language.

Warner: Even if they were geographically close, linguistically, they were very far apart.

Sandoval: Yes, some Indigenous communities for sure.

Warner: Okay, so you start to navigate this really on the plains of what is now the United States and the first peoples here, and naturally then you become interested in what the hands are doing in some of these Mayan symbols, I guess.

Sandoval: Yeah, by some strange series of events, I end up at the Metropolitan State University of Denver and start working with a person by the name of Robin Quizar, who had retired at that point, but she had done work with the living Maya language called Ch'orti', and she took me to Honduras and Guatemala for my first time. So for the first time in my life, I was looking at these ancient monuments and seeing all these hand forms, these interesting... And I was like, "That's sign language. How come I haven't heard of this?” I've read quite a bit on the topic. This seems like it should be a big deal.

Warner: And your eyes were trained to look for this, it occurs to me.

Sandoval: Yeah.

Warner: What do you feel when you're at this site?

Sandoval: I've been there three times now. I, like so many other people, was just in awe at the whole site in general but this site in particular, there's writings of Altar Q going back to the mid-1800s, and some people say Mesoamerican archeology almost starts with this monument. It's such a unique and interesting and obviously important bit of sculptural monument in the middle of this field, and it's right next to the great pyramid in Copán, their biggest pyramid. It's a few feet from it and kind of in this squared plaza that has these directional significations and things like that. I feel what a lot of people feel when they visit an ancient site, I guess, this kind of wonderment. What was it like to be there? What was going on when this place was more active with the people who built it?

Warner: You can't help but start to fill in the blanks and imagine the movement of people and the lives that they lived. Am I imagining that Mayan people would have been making these signs themselves or just carving them into figures?

Sandoval: That's for me, another reason why this is really important, and not just for me. I've been talking with other people interested in this bigger kind of issue of, and this gets back to the Arapaho, right? This really unique situation in Indigenous America where you have a number of communities, not just Deaf, but broadly speaking, people and communities using these sign language traditions and practices to communicate, like we were saying earlier, across borders, but linguistic borders and cultural borders, but also incorporated in a variety of different ways. With the Arapaho that I observed, it was a way to kind of highlight really important information and jokes and other kinds of narratives. In conversation with the Maya, it was a kind of second script that went along with their hieroglyphic script. So that bigger issue of how old and how broad was the signing tradition?

Warner: Yes, and was it embodied? How embodied was it versus pictorial?

Sandoval: Yeah. For me, I don't have enough evidence to really say. These hieroglyphs and these figures with these unique hand forms go back well before the monument that I researched a thousand years before at least. So when they first started carving these things, did it mimic kind of a living sign language at that point and then kind of take a life on its own? Which is kind of what I think, that this form of writing and inscribing with these hand signs was its own type of writing.

Warner: Inspired by the movement.

Sandoval: Yeah. From earlier on, but kind of took on a life of its own, just like, yeah, written English and spoken English have quite a bit of differences in use and everything.

Warner: I gather that based on what you have learned at this one site, the idea would be to see if you can broaden then your scope and start to confirm this over larger areas.

Sandoval: For sure.

Warner: I mean, you have a lifetime ahead of you to do this.

Sandoval: And I'm hoping many, many other people will join in. There are a few other people working on this issue from different perspectives, and I would love to build on dialogue with them. But it's not just the Maya. You find this in other ancient Mesoamerican texts and styles. The Mixtec's books are full of these kind of figures with these unique hand signs, for example. There's a number of different ancient Mesoamerican societies. The Maya, they wrote on everything and they did the most, and they were the most prolific and had the most going on. So we have more evidence from them than anyone else.

Editor's Note: This story has been updated to include a transcript of the conversation.