Go into any high school cafeteria and you’ll see kids often sort themselves by race. But a group of teachers in metro Denver this semester is making a concerted effort to show their students - through history and science - how race is not what we think it is.

South High sociology teacher Hayley Vatch is one of those teachers. For the past six weeks, she’s led her seventh-period class of Asian, black, Latino and white students on a journey examining the historical roots of race and racism as well as the role stereotypes and bias have on people today. The students came to understand that race is, in fact, an invention -- a social construct.

Why study race?

Observing the day-t0-day interactions between students, something troubled Vatch.

“Even though our school is very racially and economically diverse, I still frequently observe evidence of deeply-held stereotypes by students, as well as occasional racist jokes and the widespread use of racial slurs,” she said. “I notice that while many students feel uncomfortable when this happens, they rarely do something to stop it.”

It’s easy for students to feel hopeless about the issues of racism and stereotypes, “so I want them to see how this problem has been created over time, and how they can play a part in undoing the issue of racism.”

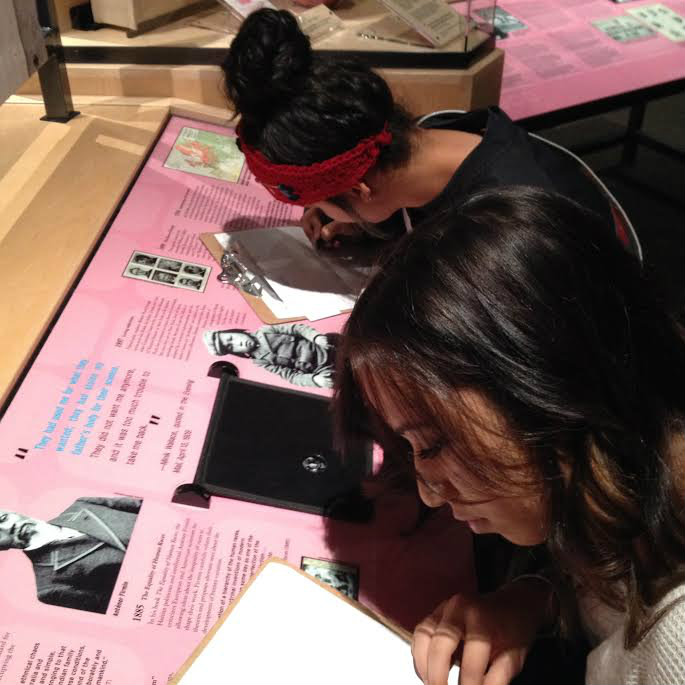

Recently, the class attended an exhibit called “Race: Are We So Different?” at Denver’s History Colorado Center. Through historical archives, multimedia installations and displays, the exhibit shattered many of their notions about race.

Everyday experiences

The exhibit features video installations of people’s experience with race – from the Native American performance artist who “dresses like an Indian” for tourists, to students talking about why races separate in the cafeteria.

The field trip helped some understand some of what they’ve experienced in life. Maribi Estrada was 10 when she slept over her best friend’s house. Her friend was white. Maribi overheard her friend’s grandmother, complaining to her friends’ father. She was upset that Maribi was staying over.

“She was talking about how Mexicans were dirty sewer rats and how they steal and stuff," Maribi said.

The exhibit gave students like Maribi a chance to continue unraveling how the racial hierarchies that fueled that racist insult developed. It gave others a chance to think about the racial divisions that still exist in their lives and at their own school.

“Kids will move away from the black kids at school because they’re afraid of getting beat up but they won’t hang out with the Mexican kids because of their music,” said Eric Caldera. “It doesn’t apply to me, but it’d be a lot better if things weren’t that way.”

How race became institutionalized

One part of the exhibit focuses housing segregation, when, beginning in the 1930s, banks practiced “redlining.” That was a rating system to measure mortgage lending risks in residential areas.

Places where people of color lived were rated lower. Though the federal Fair Housing Act of 1968 outlawed redlining, housing discrimination continues with the practice of “racial” steering into particular neighborhoods.

Many students realize for the first time just how segregated their own neighborhoods are now, 45 years later.

“I wasn’t aware at all, probably because I live in isolation,” said Jack Albeck who lives in Denver’s Washington Park neighborhood. “I have no people of color in my own neighborhood. I didn’t know [housing segregation] was still a problem – you think everything’s getting better, but it’s not actually.”

The students learn that the meaning assigned to different races has powerful consequences – like who has easier access to education, and political and business power.

Stress and racism

One installation lets students check their blood pressure. A study comparing Africans to African-Americans shows the latter have higher rates of high blood pressure -- due to diet, lifestyle and the stress of racism.

But two African-American boys say they don’t feel that kind of stress in their lives.

“I don’t stress about it on a daily basis maybe if something occurs if I feel some racism going on, then I stress about it but I don’t just wake up and go, oh, I’m inferior to white people,” said student James Hardy.

But there’s a feeling that runs through all of my interviews with these students - especially those of color - that the world, the white world, perceives them differently.

But there’s a feeling that runs through all of my interviews with these students - especially those of color - that the world, the white world, perceives them differently.

"There’s a difference that everybody puts on black people, they don’t expect them to act civilized," student Trevonte Tasco said. "They expect the white people to act civilized and more mature."

For some, this sense that they are perceived differently has an impact on their own self-perception.

“I feel like I don’t have the same privileges as the white people do," said Adeline Reyes, a Latina student. "I feel like I can’t be higher than them, like I’m always going to be lower than them.”

Social, not scientific differences

Sorting people by physical differences is a recent invention, only a few hundred years old. Early scientists tried to distinguish races by measuring facial slant, and then skull size, which has nothing to do with intelligence. But the notion of human biological races persists because of early scientific attempts to distinguish races.

Scientifically, no one gene, or any set of genes, can support the idea of race. Two fruit flies are more genetically different than two humans from opposite sides of the globe.

That biological variation is not racial is astonishing and new to many students.

“The thing about genes, how race has nothing to do with genes -- I never would have thought that,” said Hardy.

Race is only skin deep, the students learn, and that’s only different because of the intensity of the sun depending on where our ancestors are from. And that makes them start to think about each other a little differently.

“ 'Cause we’re all kind of the same, said student Reilly Aasal. “You can’t point a finger to someone and say you’re different so you should be treated differently. It's that we are all basically human. There’s no race besides the human race.”

To culminate the month-long examination into race, Vatch has the students write a six-word sentence encapsulating their thoughts on race.

- I’m not illegal, thanks for asking.

- Skin color doesn’t mean a thing.

- Race is the first thing seen.

In essays, students then explain their sentence using materials they’ve read, watched, and discussed in class along with their own experiences. Here's one from student Mariba Estrada.