On the first day back from Thanksgiving break, teacher Hayley Vatch’s first question to her last class of the day is a bit of a doozy: “Raise your hand if you thought Darren Wilson would not be indicted?”

Less than half the racially diverse sociology class raise their hands.

Darren Wilson is the white police officer who shot and killed Michael Brown, an 18-year old African-American. A grand jury in Ferguson, Missouri recently decided not to bring criminal charges against Wilson.

Wednesday and Thursday, students at several Denver high schools walked out of their classrooms to protest the decision. But Vatch’s class at South High School in Denver has spent the entire week talking and writing about the decision -- and about the larger issue of why it’s sparked so much anger.

Rasikh Abdelmonim, the first to speak during the class discussion, said he expected the decision.

“It was upsetting to me, [Wilson] shot a person six times, and didn’t go to prison or get anything at all. He’s just walking the streets like Zimmerman,” he said, referring to George Zimmerman, the Florida man who was acquitted last year in the shooting death of Trayvon Martin, a black teen.

Many of the students have a hard time understanding how the officer who killed Brown in Ferguson faces no consequences for his actions.

“The fact that he didn’t get charged with anything -- it’s just disgusting, to be honest,” said Sarah ElBoukili.

An ongoing discussion

Brown’s death can be emotional and challenging to discuss. But the tough topic of race isn’t new to Vatch’s class. They’ve dug into the topic for weeks now, investigating the roots of race and racism.

The issue is a real one for students in this multi-racial class. Luna Tesfay, who is black, was stung by a recent encounter in which she was compared negatively to white students. Then she saw the pictures of Ferguson protesters lying on the ground.

“What’s the point of living if we’re just going to be judged off of our color?” Tesfay said. “It’s not fair.”

It’s important for students to process what they see and hear and to give them tools to think about race, Vatch said. Ferguson was another chance for her students to look at how race, class, law and justice intersect. She wanted the class to be informed about the facts.

It’s important for students to process what they see and hear and to give them tools to think about race, Vatch said. Ferguson was another chance for her students to look at how race, class, law and justice intersect. She wanted the class to be informed about the facts.

“But more importantly,” she said, “about the larger issues of who's feeling oppressed and why and what are their reasons for that and then what can we do as individuals and also as a country to get rid of these negative feelings.”

Investigating complexities

Many of the students are unaware of federal and state laws. Vatch explains that the law protects police if they believe deadly force is “immediately necessary. She explains that for many people, the conversation has shifted to whether the laws are good laws. Vatch helps the class unravel the complexities of the case, and what they think needs to happen now.

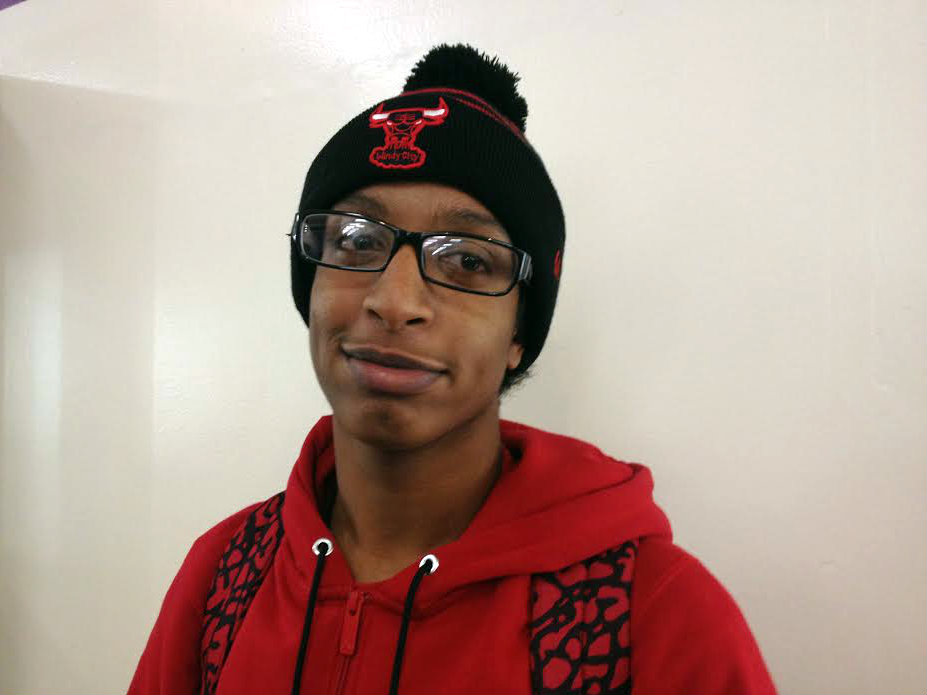

“I think the law needs to change a little bit,” says student Trevonte Tasco. “Like, you shouldn’t always be able to pull out your gun and shoot. You should have a reason, like, if the person has a weapon against you, then you have protect yourself so then you have to use it, but if he doesn’t, there’s no point in even using it.”

The students discuss articles they’ve read on the power of protest vs. rioting and whether “race” or “class” matters most. Then Vatch has the class take turns reading parts of a viral Facebook post written by NFL player Benjamin Watson.

In it, Watson tackles his conflicting feelings about Ferguson after the grand jury decision, like being confused about why it’s so hard to obey a policeman, while also not understanding why some policemen abuse their power.

I'M INTROSPECTIVE, because sometimes I want to take "our" side without looking at the facts in situations like these. Sometimes I feel like it's us against them. Sometimes I'm just as prejudiced as people I point fingers at. And that's not right. How can I look at white skin and make assumptions but not want assumptions made about me? That's not right.

“A lot of times people feel they have to pick a side -- the side of the person they look like sometimes -- but I wanted them to feel that it’s OK to not be quite sure,” said Vatch.

Difficult, important conversations

Student Reilly Aasal said people make assumptions about her step-father all the time. He’s white, “looks like a biker,” and has a lot of tattoos. She said he’s stopped by the police a lot.

Aasal, in a Martin Luther King Jr. T-shirt, considers herself open-minded. She’s enjoyed learning about the roots of racism. But even in a class like her sociology class, where race is the main topic, she said it can be awkward sharing her views openly. She believes Brown escalated the situation.

“I’m white, so they’ll be like, ‘Whoo, racist,’” she said. “[Brown’s death] is nothing about race at all. He was in the wrong, whether he was white, black, Chinese, anything, he was in the wrong. He tried to fight a police officer and grab his weapon.”

But like her classmates, she doesn’t think he should have been killed, and there should have been a trial. Still, talking about tough stuff like race in high-school, Reilly said, is good.

“The awkwardness isn’t a bad thing in the class,” she said. “It’s just there.”

Vatch said at the outset of a course like this, students are afraid they’ll offend somebody. They don’t want to say the wrong thing and, as teenagers, they’re also conscious of what their peers will think of them. But she said most students have found the classes on race helpful.

And she tells them, at the end, if they have more questions or confusion than at the start, that’s good. It means they’re thinking.