Katrina Haselgren sits outside with her 3-year-old son Giovanni having "mommy and me" time. Her older sons are at school.

“What’s that noise?” she asks him gently.

“A grasshopper,” Giovanni says softly.

The neighbor’s big dogs suddenly run to the fence, barking loudly. Giovanni looks startled. Haselgren is calm and reassuring.

“Was that loud?” she asks.

“Mm hmm,” he replies.

“But it’s OK, huh?”

The scene is a far cry from the chaotic and violent home life of Katrina Haselgren’s childhood. Her step-father routinely beat her mother, who paid little attention to Haselgren. She felt no love.

“I would lash out and I would beg for help,” she says. “I needed someone to advocate for me.”

As she and Giovanni play with monster trucks, Haselgren looks at what her son is looking at, repeats the word he intends rather than the word it sounds like he's saying. These are techniques she practices on a daily basis. Haselgren marvels at how fast her young son seems to be learning.

“When he sees that I am into what he’s into, then his vocabulary comes out and he tells me words that I didn’t even know that he knew,” she says. “It’s just when he knows we’re connected to the same thing and we have something in common, then he wants to know my input too.”

“A lot of yelling and a lot of distance”

That close, warm communication wasn’t there with her older sons. They have been exposed to a lot. They’ve seen their mom beaten, become homeless, and Haselgren discovered, she was treating her sons in the only way she knew how – like her parents treated her as a child.

“There would be a lot of misunderstanding and a lot of yelling and a lot of distance between us,” she says. “There was never understanding and role playing with them to show them, ‘this is how you learn.’”

Raising four sons alone without much money, Haselgren struggles. One son has cognitive problems, another has ADHD, and the oldest has autism. But Haselgren is determined to become a better parent. She worked tirelessly with her oldest; he's now on the low-end of the autism spectrum. And as luck has it, Halsengren’s youngest Giovanni attends Clayton Early Learning where Haselgren also volunteers.

It’s a high-quality early learning center mainly for disadvantaged children like Giovanni. Some come from situations of stress or trauma.

“Children come to us and they may feel insecure. They might be afraid. They might be in fight or flight mode. They might be having difficulty connecting with others," says Cathy McCarty, vice president of schools at Clayton Early Learning.

“When you’re in those areas of the brain, what’s happening is your brain architecture is building around those experiences,” she says. “What isn’t happening is when your focused on, ‘I can’t get along with my friend,’ you’re not in a place developmentally where you are ripe for learning new things because you are stuck in theses lower areas of the brain.”

If a child doesn’t feel safe, things like problem solving, the ability to self regulate or develop memory and attention are put on the back burner.

Buffering children from toxic stress

But what if you could find a way to "buffer" children from the toxic stress?

Enter Sarah Watamura, director of the Child Health and Development Lab at the University of Denver. Her project is one of six federally funded studies across the country. Each site is testing a different promising intervention to help parents in the poorest families boost child development.

“So start with a family,” Watamura says. “Understand all the stressors they’re facing, all the strengths that they have and then look to see how that child is developing across those first few years of life and even try to give some strategies that parents can use to try to protect the child from the consequences of those stressful experiences,” says Watamura.

Clayton Early Learning is her team’s testing ground. That’s where Katrina Haselgren learned skills she says that have changed her life. She was part of the group that received multiple interventions, and individual therapy. The six-year study is measuring a number of indicators like the child’s physiology, emotional health, cognitive development, and the relationship health between mother and child.

Watamura explains that intervention "coaches" don’t know whether families are or aren’t stressed. Nor do they assume there is any problem with parenting.

How communicating is like tennis

Here’s how the Harvard-developed intervention works:

Coaches explain to the family that the way a child develops their brain is through a concept called "serve and return." Basically, all day long, your child is serving a ball to you.

"You have to pick up on those cues and make an appropriate return,” says Watamura. “That back and forth, that give and take is what’s helping them connect to all these concepts in their mind, label them with the right language and build literally the architecture of their brain.”

Families are videotaped. In her office, Watamura watches a tape of Katrina Haselgren and Giovanni at age 2, interacting. Coaches review clips of “microsocial” moments with the parents and show them what they’re doing right. They don’t use any corrective feedback. The coaches help parent and child build on strengths.

In the video Giovanni points to his toy -- a cow.

May 20: Research shows stress can be toxic for kids who live in poverty

May 19: Poverty changes a mother's brain and her baby's as well

"Mom is oriented to baby,” Watamura explains. “She’s looking at what he’s looking at so when she makes that vocalization, she can say yes, that’s his foot. So she’s labeling the correct part for him. She’s paying attention to what he’s paying attention to therefore validating all the things that he’s interested in and sharing that moment together.”

And then Giovanni points to his own foot.

In the video, Haselgren helps Giovanni make the connection to his foot.

“[She says] right just like your foot,’ so now he’s able to connect the concept of foot, I have a foot, the cow has a foot’," says Watamura.

What parents can do

There are five key components of the intervention: sharing the child’s focus, supporting and encouraging (adult adds his or her own reaction by acknowledging what the child is seeing, doing or feeling), naming (labeling what the child is doing, seeing, or feeling), back and forth interaction (interaction continues, with the adult waiting for the child’s further initiations), endings and beginnings (when the child signals that a back and forth interaction has naturally come to a conclusion, i.e., the book is finished.)

There are five key components of the intervention: sharing the child’s focus, supporting and encouraging (adult adds his or her own reaction by acknowledging what the child is seeing, doing or feeling), naming (labeling what the child is doing, seeing, or feeling), back and forth interaction (interaction continues, with the adult waiting for the child’s further initiations), endings and beginnings (when the child signals that a back and forth interaction has naturally come to a conclusion, i.e., the book is finished.)

“Young children are really looking for those high, positive interactions where adults are using really modulated speech, that’s how they learn,” she says.

Once parents understand what the baby or young child is expecting from them, Watamura says it comes naturally.

“Most of the parents they work with, they’ve often been told what to do but not why,” she says. “Once they understand that, they really don’t have difficulty with this concept. It’s just they have so many pressing concerns, taking the time for this … we have to increase the importance of this, you know, ‘you’re not going to get this time back and this is literally how you’re child is building her brain.”

It’s just a matter of making that a priority over all the other pressing matters parents face. Some researchers hope eventually, the issue of toxic stress is as front and center in parents’ minds as lead poisoning.

New parenting style put to the ultimate test

Katrina Haselgren says what she’s learned has also changed her relationship with her older sons.

Instead of telling them what they can’t do, like her parents did with her,“now everyone’s learning,” she says. “They’re in the kitchen with me, they’re cooking with me, they’re doing their chores... (I'm ) not only telling them what they can’t do but telling them what they can do but filling up their piggy bank with positive feedback.”

But those routines were thrown out the window recently when the landlord sold their house. Now, the family is homeless.

“Momma, where we going?” asks 3-year-old Giovanni, one recent late afternoon as dark thunderclouds gathered outside. Haselgren hasn’t slept in 24 hours. She’s so stressed. The family is sleeping on a friend’s floor. They have to get up extra early to get the kids off to school across town in Green Valley Ranch.

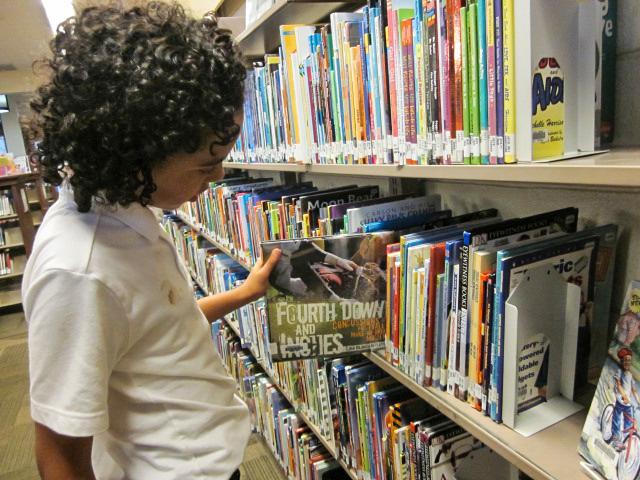

But after school, they stop off at the library so the kids can check out books and a movie. She gently chides 10-year-old Elijah when he doesn't put a movie back on the right shelf.

“Ah! -- put it back where it belongs please,” she says.

She then patiently teaches him how to check the books and movies out. Outside the library, she has a little check-in with the kids.

“I know our situation is a little rocky right now,” Haselgren says. “We recently moved from our home, right? And now we’re all over the place, right? So it’s not really settled. We’re not in our environment. We’re not in our daily routine, and now we’re all over the place – right? How does that make you feel?” she asks.

“The stuff that I like to do at my house,” says 10-year-old Elijah. “I can’t do it no more ‘cuz it’s a small space for us and we got to follow the rules.”

Normally, the family has discussions like these at something they call the "peace table." When there’s a problem or a conflict or a fight at school, Elijah says they go to the peace table to resolve it.

“Like when I get in trouble at school, I come home to tell my mom, she says, ‘let’s go sit at the peace table, we’ll talk about it,’ then when she knows what happened, she’ll talk to the school about it,” he says.

But the family doesn’t have their peace table anymore. They had to leave it behind, along with the rest of their furniture, when they had to leave their last house.

Haselgren tells them, “we still have the peace table in our minds.”

She says she’s dedicating her life to make sure her sons have a fighting chance, the chance she never got. She says the study is the best experience she’s ever had.

“It’s helped me connect with him [Giovanni] on a level I never connected with my other kids before,” she says. “I got the tools to not only connect with Giovanni but with them on the same level… . I am a 29-year-old single mom of four wonderful boys. And if I can do it, anyone can.”