Gerardo Vargas leans against a post in an Aurora Central High School parking lot. He’s watching his youngest son practice soccer on a school field across the street.

Two of his children have already graduated from the high school, the oldest in the district, with honors. But Vargas has heard that test scores at the school are low, and he still remembers what one of his sons told him.

“He told me the teachers don’t worry if you haven’t done your homework,

Vargas said in Spanish. "They don’t do anything but show up, give the class, and leave."

His youngest son is a freshman, one of more than 2,000 to head back to school last week. Vargas said he’s a sensitive boy and a good person. He told him, "you are going into a lion’s den." Vargas is giving the school a year.

“If it works, we’ll leave him,” he said. “But if not, we’ll look for other alternatives.”

That may not be fast enough.

Big change may be coming

Aurora Central has been on a state watchdog list for four years because of low test scores and graduation rates. That means while the school keeps trying to improve this year, the district must plan to make dramatic structural changes to the school starting next year.

“We are in a model that is not meeting the needs of our students,” said Gerado De La Garza, Aurora Central’s new principal. He knows the test scores are dismal. In writing, just a fifth of students are at or above grade level, in reading 35 percent, and in math, a little over 10 percent are on target.

De La Garza’s only been on the job a few weeks so he’s doing a lot of listening and observing. He said if he sees anything getting in the way of students being successful, he’ll make adjustments. He wants to see administrators and teachers in the hallways at passing periods, greeting students.

But the district will spearhead the really big task of remaking the school. That project is expected to take a year.

Fixing a school is complex business. And everybody’s got an idea for what works. You could replace teachers or invest in the ones you have, helping them get better. You could lengthen the school day, make students wear uniforms, or give them more career-related training. Some point to “bureaucratic red tape” as being the culprit that grounds progress to a halt, and that appears to be what district leaders are pointing to.

Right now the idea is to make Aurora Central part of an “innovation zone.” That would give it flexibility to take teachers off a contract (if they agree), let the school set its own schedule, and its own curriculum.

“Is the curriculum the right curriculum for our changing demographic?" De La Garza asked. "If it’s not, then let’s make the necessary adjustments.”

Diverse student body a challenge -- and asset

The school’s changing demographics reveal that low test scores are only part of the school’s story. The student body is a rich tapestry of students from around the globe, from countries as far flung as Mexico, Nepal and the Congo. Many of them have intensive academic, social and English language needs.

A group of boys on bikes lounge outside the school. They’re speaking Karen, one of the languages of Burma. It’s just one of 50 languages spoken at Central. Pare Reh, 15, was in refugee camp in Thailand for eight years -- half his life. Though he came to the U.S. in 2009, Reh still barely knows English.

“I don’t know how to write,” he said. “I don’t know how to speak little too much. Very hard for me.”

His friend translates when Pare said one main thing that needs to change at Central is students need to listen more to the teachers. But sometimes his friends say, it’s so hard to understand, that it’s often easier to ditch class.

Two other boys say if you failed tests in their school in the refugee camp, “every day they hit you with stick,” one said.

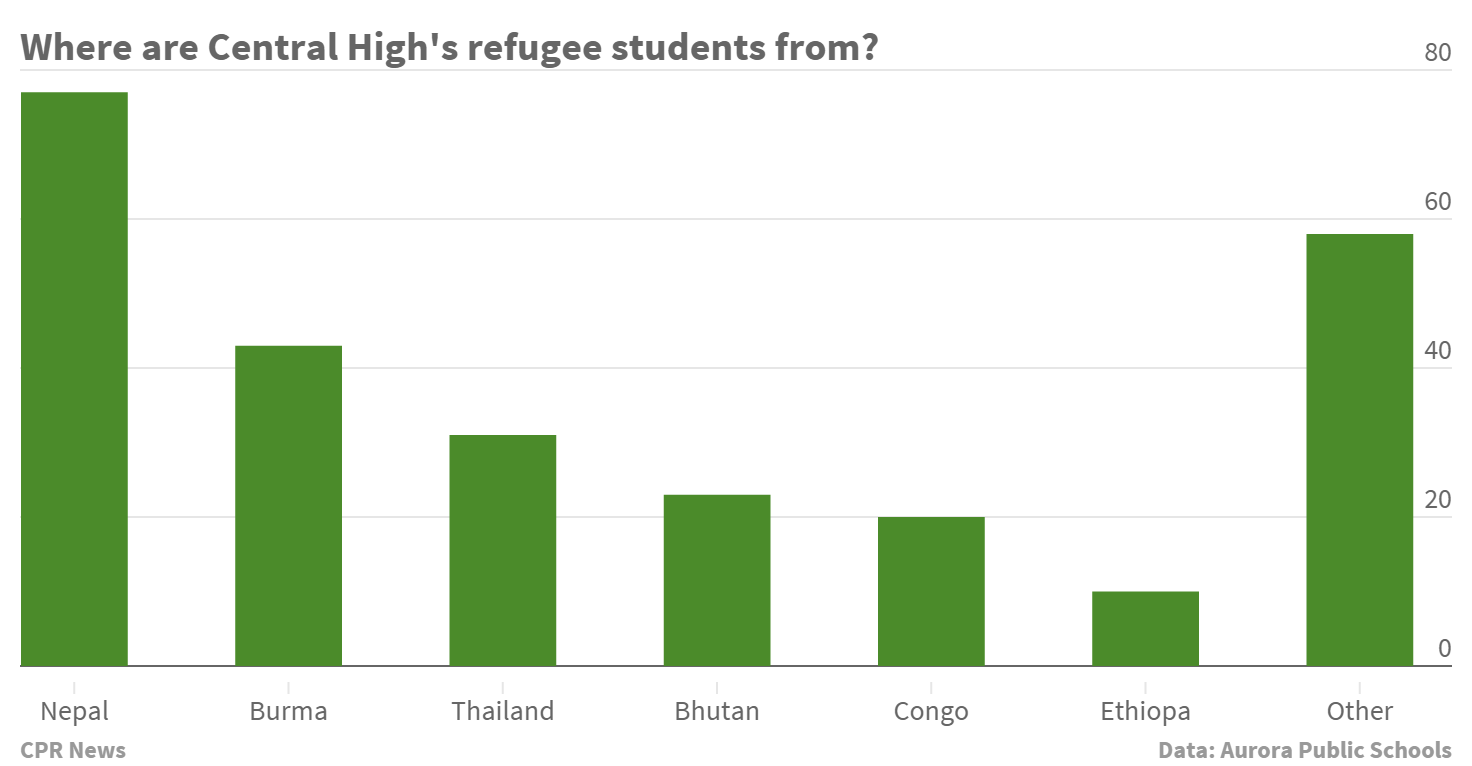

That illustrates just how much of a shock, even culturally, school is for many students here. Aurora Central has challenges many schools don’t have: Forty-three percent of students English language learners, much higher than most of the other Aurora high schools. And there are 262 refugees, the highest of any metro Denver high school.

“Anytime there’s a political hotspot, anytime there’s a war, anytime there’s a coup,” said parent Becky Finnie, soon “you’ll see students from there at Aurora Central.”

Finnie said to evaluate a school by test scores – with that high of a refugee and English language learner population -- isn't fair. It would be like asking a English-speaking American to take a test in Chinese after a week in Asia, she said.

Finnie said the Central’s diversity has been a boon to her sons. They’ve excelled here. One went on to the Colorado School of Mines.

“Aurora Central has some really very good teachers, very dedicated, I think characterizing the school as failing is a mischaracterization,” Finnie said.

Other students bristle at the school being judged by test scores. They say it’s too simplistic and doesn’t reflect the hard realities of many students’ lives. Jesus Dorado, who got an “A” in a college-sponsored math class last year as a sophomore, is one of them.

“I know a lot of friends that just work,” he said. “They don’t even have time for homework and it’s not because they want to work, it’s because they have to help out their parents.”

Where's the path to success?

Some of the students we spoke with believe they’re getting a good education. They know the school has weaknesses – several pointed to security being too lax on drugs. They also seem to know what national research says about turning around a school -- it can take up to seven years. One strategy in innovation schools is to bring in new leaders and teachers. But Dorado said they should give established teachers more time to get to know students.

“I heard that a lot of new teachers are coming in," Dorado said. "But in reality, I don’t think it’s going to fix it in just one year."

Teachers like Monique Taylor are hopeful the innovation might come with more assistance, like for English language learners for instance. But not knowing the plan now is difficult.

“It’s stressful because it’s kind of like an unknown,” she said. “I think we just need to make sure we have input from everyone, all the stakeholders. That means the parents the students, the teachers, administrators, everybody needs to have input into what happens and how this school functions in the future.”

Jesus Dorado’s friend, Michelle Figueroa, thinks “innovation” could make a better school, bringing more opportunities for students. But as for this year:

“I feel like it’s going to be just like it was before Dr. Roberts came in,” she said.

Mark Roberts, the principal last year, was recently moved to another post in the district. Aurora Central has now had three principals in three years. Research shows the constant shuffling of principals at high poverty schools does take its toll. Research also shows that when it comes to “innovation” schools in Denver, that status hasn’t boosted improvement significantly.

But new principal De La Garza isn’t daunted. He acknowledges it’s challenging and there is no magic bullet.

“If we were doing everything the right way and we were being successful at it, then we would see different achievement results,” he said.

But Ellie Tchilembe, who plays on the school soccer team, believes it’s not a grand new scheme that will change the school. He said it’s attitude, effort and pride on the part of students that will make the difference.

“We need school support. We need to be proud of what we are, even in our difficulties," Tchilembe said. “Because the school isn’t the building; it’s the students who are the school.”

And it’s the students who will play a big role in determining whether the school gets better results.