Like most students, Eaton High School senior Karalee Kothe had never thought about her school's mascot -- the Fightin' Reds -- really deeply.

Then last year, she heard about state lawmakers who were pushing a bill that would have created a committee to review the use of potentially offensive Indian mascots. If the committee – or a tribe – found one to be offensive and the school still had the mascot after two years, it would face a fine of $25,000 a month.

The bill didn’t pass, but it got Kothe thinking.

"I was like, ‘Hey what about our mascot?'" said Kothe, who's also the editor of the Red Ink, the newspaper for the school located just north of Greeley.

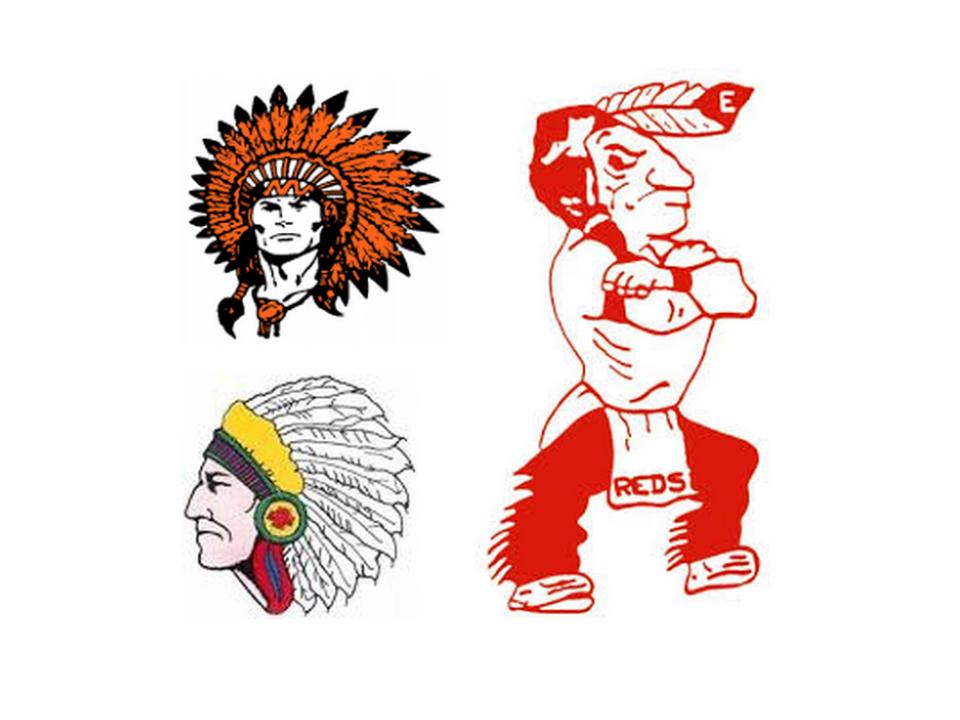

The Eaton mascot is plastered in the middle of the gym floor, on the walls, on students’ uniforms. It’s a cartoon-like caricature of a Native American.

“He’s in an aggressive stance, so it’s just not very realistic and many would say it’s not very honorable for Native Americans,” said junior Devan McKenney.

The caricature wears a feather – a spiritual symbol sacred to many Native Americans - with the letter “E” on it. The word “REDS” is written on the loincloth.

Why An Indian Mascot?

After the controversy generated by the legislative bill, the newspaper staff began researching why the school had the mascot in the first place. They learned that the school was represented by the single letter “E” for 65 years -- longer than it's used the Indian mascot.

Eaton's new mascot was part of a larger trend of Indian mascots that were the rage in the 1950s and 1960s, according to history teacher Chad Shaw who wrote a master’s thesis on the topic. He found that in 1966, Eaton High’s athletic coach and PE teacher Ken Ridgely decided to create a mascot, determining that an Indian goes best with the word “red.” He found a picture in a book, and without official permission, affixed a large image of it in the gymnasium.

“Unfortunately in the history of Native Americans in this country, 'red' was the term for the scalps that were collected through Indian bounty hunting days in the 1600s and 1700s,” said Shaw.

That image is Eaton’s mascot today. Eaton is one of 38 Colorado schools that has an Indian mascot. It’s a contentious issue around the country. Some states have banned the practice; others are still deciding what to do.

The Commission to Study American Indian Representations in Public Schools was created by executive order last October. The objective was to hear what communities think about their mascots rather than force a school to convert its mascot. The commission will release its report and recommendations to the public on Monday.

A Range Of Opinions

Eaton’s mascot is pretty popular.

“As our mascot, it brings everyone together,” says junior Dalton Waln on a break from track practice. “It’s something that almost keeps our school together.”

Red Ink staffers surveyed teachers and found more than half of them wanted to keep it. Eaton District Superintendent Randy Miller doesn’t have a problem with the mascot, either. He’s focused on the estimated $50,000 to $100,000 it would cost to strip the gym floor of the red cartoon man and change school uniforms.

“That’s taking computers and other stuff away from the children," Miller said. "I can't see doing that. That’s not a good thing.”

Red Ink staffers surveyed teachers and found more than half of them wanted to keep it. A survey of students found 68-percent didn’t find it offensive. For newspaper editor and senior Karalee Kothe though, the more research she did the more personal it became.

“Native Americans were persecuted for so many years and the Sand Creek Massacre was just a few hours away from here where hundreds were slaughtered and for us to have the nerve to continue having the mascot, I don’t know, it just hurts in the soul.”

Kothe wrote an editorial against the mascot.

“When she wrote that editorial, I said are you ready for the heat you are going to get on this?” said the Eaton Red Ink advisor Deirdre Jones, who has taught at the school for a couple of decades.

Jones has had her own personal journey on the mascot issue. She recalls many years ago, coming to school wearing a staff shirt emblazoned with the Indian caricature. Social studies teacher, Tom Trotter, challenged Jones about her choice of attire, calling the shirt “racist.”

“I am a not racist," Jones said. "And when he explained it to me I thought, ‘How? How could I have not seen that? How am I blind to that?' I was so inculcated from Daniel Boone and cowboys and Indians and John Wayne that I didn’t even see.”

Jones has come to believe the mascot is not just damaging to Native Americans, but to all students.

The Red Ink staff has a variety of opinions about the issue. But they all tried to be open-minded as they researched. Newspaper reporter Cameron Moser understands how living in a small town fuels a sense of pride around a mascot.

“When someone comes in and says something like, ‘your mascot is racist,’ I can see why people get a little rustled," Moser said. "Since [the town] is so small, you’re so close to it, it feels like more of an attack on you as a person than the mascot or something abstract like the mascot."

When Kothe heard about Hickenlooper’s commission on Indian mascots, she got on the phone and invited the commissioners to Eaton. The students would host a community forum – the last on the commission’s tour – to start a dialog.

“I feel like if people knew the full history, they wouldn’t cling to the tradition as much,” Kothe said. “I think if the mascot is going to be changed it has to come from within the community.”

Commission Pays A Visit

In March, the night the commissioners arrived, the students gave them a tour of the gym. Tyson Thompson, a member of the Southern Ute tribe, looked at the large mascot in the center of the gym. Then Thompson stood next to an image of the mascot on the wall.

“Does he look like me?” he asked the two students accompanying him.

They seemed too embarrassed to answer. But Sydney and her sister Leslie Tucker were eager to learn. They chatted and Thompson gently explained why Native Americans would find the floor’s image of the mascot with a feather with an “E” on it – offensive.

“It tells a history of who we are,” Thompson said. “We would never put that on the floor because you would be walking on it and that’s disrespectful.”

The girls agreed.

About 60 people showed up to the forum. Commission member Darius Smith gave the history of the issue and how some Native Americans feel about it. He talked about how Indian mascots are seen as a form of bullying.

And he gave a timeline of Colorado high schools that have abandoned offensive mascots, or altered them by working with a tribe to create a more authentic and respectful mascot -- like Arapahoe High in Centennial.

Almost two decades ago, the school got permission from the Northern Arapahoe tribe to use the mascot. They commissioned an artist from the Northern Arapahoe tribe to design a warrior. The school and the tribe have alternating pow wows at the high school and at the reservation in One River, Wyoming. Students help with the Christmas dinner at the Denver Indian Center.

“Please Don’t Take It Away”

Then it’s the community’s turn to speak.

Military veteran Stan Snow said his bomb squadron, some 60 years ago, had a name some people now might find offensive: the Devil’s Own Grim Reapers.

“We are shrinking into a society that has to be squeaky clean and politically correct,” he said. Snow coaches one of the children’s soccer teams. He described one team when they were down three goals. They were warriors, he told them.

“You’ve never seen a more determined bunch of players,” said Snow. “Because they were behind their mascot and they were Eaton Red Warriors.”

The kids won the game. Snow said the mascot is a historical part of Eaton.

“Please don’t take it away,” he pleaded, to applause in the school auditorium.

Snow doesn’t see the mascot as derogatory. For him, it’s about pride and honor.

That’s the way it is perceived for most of the older adults in the crowd. It is the younger ones, the students, like football player Braedy Sturdevant who disagree.

“We embrace that warrior spirit but we don’t have to embrace that Indian persona,” he said. “It’s not OK.”

Sturdevant asked commission members what the students can do to change the mascot. Some suggested reaching out to a tribe to help make a symbol that’s more authentic like they did at Strasburg High, about an hour and a half southeast of Eaton.

Strasburg High school senior Lindsey Nichols, a member of the commission, told Sturdevant it starts with being willing to question traditions. Her school used to have a student run around the track in an Indian costume whenever the football team scored. Nichols says traditions aren’t always right.

Nichols has reached out to northern Arapahoe and southern Cheyenne tribes who are native to Strasburg. She suggested the Eaton students approach the administration.

Several hours passed and by the end of the forum everyone agreed it was a respectful and open dialog.

“I appreciate the spirit and the attitude you brought here today and the way you approached this, because it’s not what I expected,” said Mayor Scott Moser.

Still, no real plan of action emerged. But as the stage was cleared, editor Karalee Kothe looked slightly bothered. Asked how she felt, Kothe replied:

“Bittersweet. I’m sure a lot of people learned a lot of things about Native Americans and our mascot that they did not know before. But I’m also just sad.” She thinks most of the older people there weren’t willing to see a different perspective.

But Kothe says she’s proud of her newspaper staff for hosting the forum -- and proud of the town she was raised in.