Denver Mayor Michael Hancock’s administration is trying to make it harder for authorities to track down undocumented immigrants in the city's courthouses -- despite the federal government’s insistence that officers will remain in the hallways.

City officials, starting this month, will allow people coming to the courthouse to wait in a private building across the street so they won’t be in eyesight of agents from Immigration and Customs Enforcement. They’ve reduced municipal sentences for lower level crimes so the proceedings don’t flag attention of federal officials. And they’re allowing people to plea traffic offenses online so they can avoid the courthouse altogether.

“The city of Denver has been working on several different fronts to assure the community that we have their backs,” said City Attorney Kristin Bronson.

Does that make Denver a so-called sanctuary city? Bronson and other city officials avoid the term, calling it ill-defined, political and a misnomer that can give undocumented immigrants a false sense of security.

“There's only so much that we as a municipality can do to help them and otherwise the federal government has the right to pursue federal immigration enforcement and we're not going to interfere with that,” Bronson said.

Immigrant rights groups, lawyers and even some members of the City Council call his policies a decent starting point, but say the mayor needs to go further in standing up to ICE. They often bring up San Francisco as a model, which has one of the most aggressive sanctuary policies in the country.

City Councilman Paul Lopez is weighing whether to introduce a bill that would force Hancock to go farther: He wants Hancock’s policies written into city law and wants to explicitly limit police and city officials from working with ICE except in cases of serious violent crime.

“In the interest of public safety, in the interest of making sure that Denver police are not immigration officials, that the Denver Fire Department and the badge that they have on their sleeve is not ICE, it’s important for folks to see that there is a difference,” Lopez said.

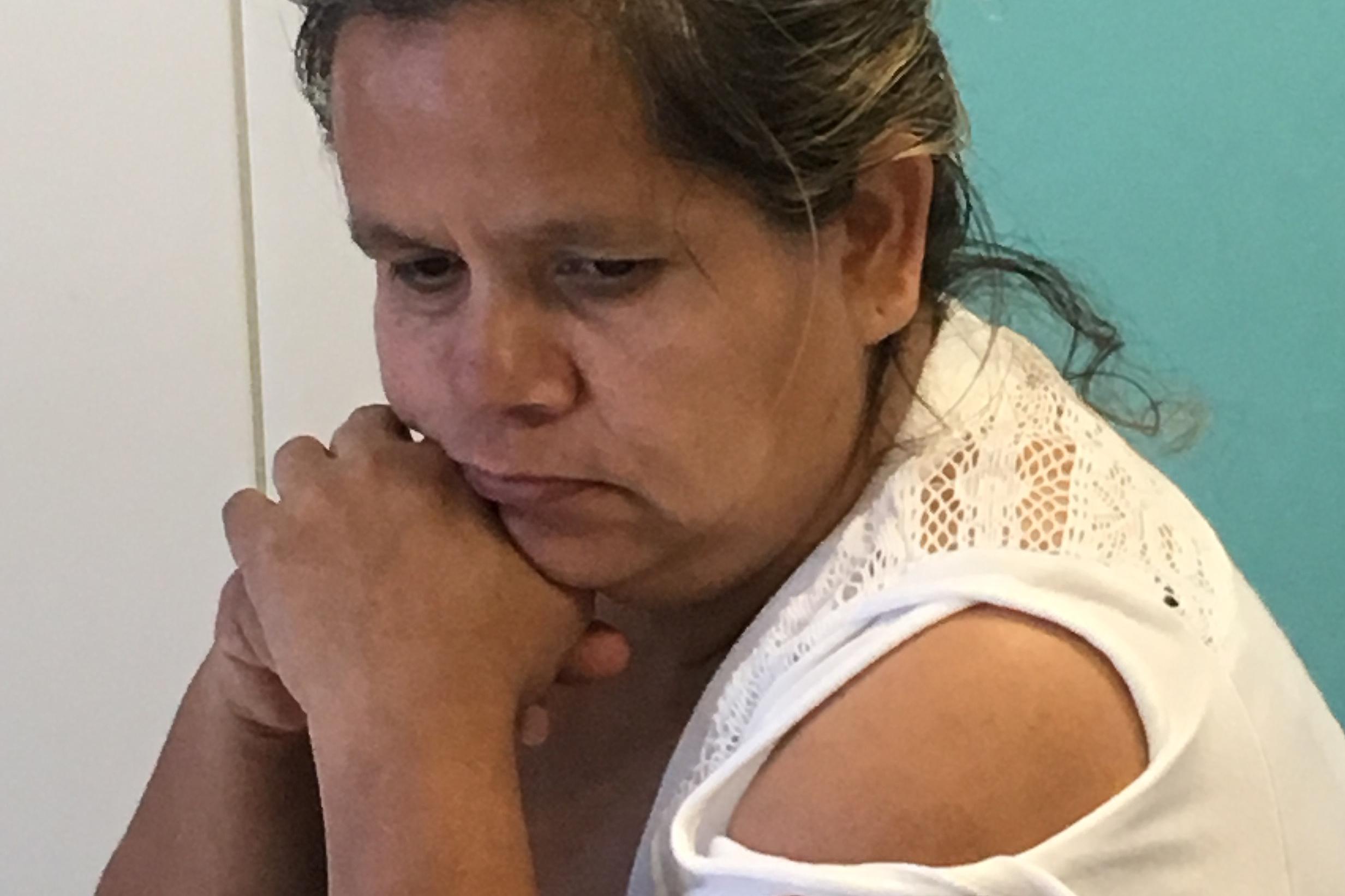

In southwest Denver, a mother whose family grapples with this tension everyday says a sanctuary policy would make her family feel more safe. Lorena -- she asked not to give her last name -- says she’s ready to march to push city officials for Denver to become a sanctuary city. Speaking in Spanish, she says her seven-year-old son asks her often what will happen if she’s taken back to Mexico.

“He’s very scared,” she said.

Immigrant advocates like Hans Meyer agree. The Denver-based immigration lawyer has been urging the mayor to go as far as San Francisco, which prohibits city officials from helping ICE except in cases required by federal or state law.

“If they're not willing to stand up for this policy at this time in history, maybe we need to find someone with the guts to do so,” Meyer said.

City Attorney Bronson says Denver doesn't want to defy federal authorities. In fact it wants to cooperate with ICE -- particularly in cases where there are violent criminals involved. That’s why this new approach has been dubbed a “safety first/welcoming” policy.

“Our federal law enforcement partners are a very important part of our public safety approach in Denver and we’ve got to maintain those relationships,” Bronson said. “So if we feel there is a practice or a policy that has first and foremost a public safely basis for it, we’re not going to be willing to reverse that just to give people a false sense of security that Denver can protect them if we can’t protect them.”

But Ira Mehlman at the Federation for American Immigration Reform calls Denver’s policy a sanctuary policy. Mehlman’s group advocates for less immigration and he’s been tracking sanctuary policies across the country.

“You know, if it waddles like a duck, it quacks like a duck -- it's a duck no matter what you call it,” he said.