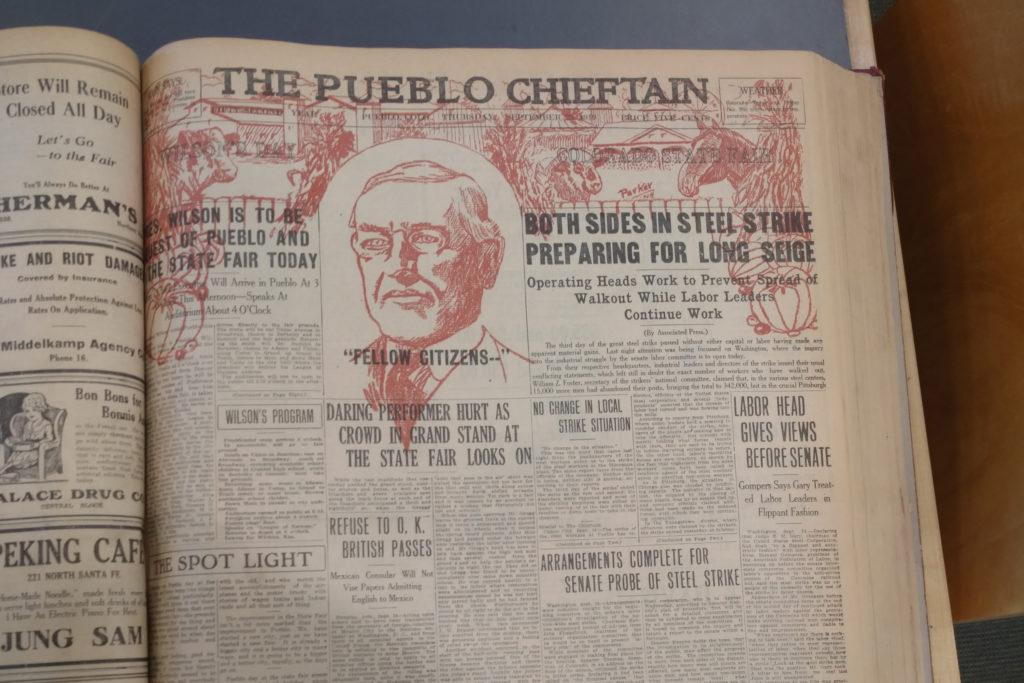

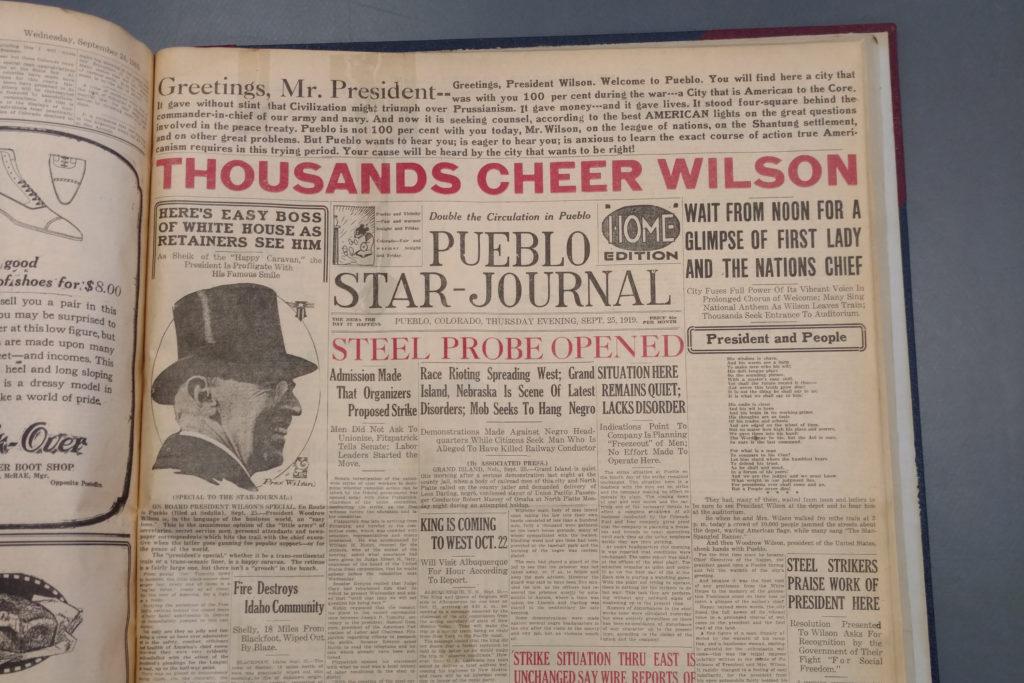

On Sept. 25, 1919, President Woodrow Wilson called on Coloradans to support the League of Nations in front of Pueblo's Memorial Hall.

World War I had ended a year before, but America was not feeling victorious. Strikes, inflation and race riots plagued the country, and the beginnings of what would become the Red Scare were taking hold.

Wilson was facing opposition to his proposal for the League of Nations in Congress, so he took his pitch to the people. But the president did not look well that day in Pueblo.

"He got a good crowd. They turned out to see him," Wilson biographer John Milton Cooper said. "(But) he was not, to put it mildly, in good shape. In fact, the strain on him was even evident to the reporters. Various reports and newspapers were talking about how the president looked tired and weary, and he stumbled sometimes getting onto the platform."

The high elevation and dry weather worsened his breathing and headaches.

After the speech, Wilson visited the State Fair before hopping on a train. He then stopped briefly to shake hands in Rocky Ford. Five more speeches were scheduled on the tour.

Later that night, still on the train, he collapsed.

"As far as his doctor was concerned, he'd been pretty good during the evening," Cooper said. "He went to bed about 10 o'clock, and then around two o'clock in the morning, he woke Mrs. Wilson, just said, 'I'm feeling terrible.' And so, she summoned the doctor, and the doctor saw that he was just in no shape to go on."

The rest of the tour was cancelled, and the train rushed back to Washington, D.C. On the night of Oct. 1 or 2, the president suffered a stroke. Wilson was paralyzed on his left side. His health would only continue to decline.

"The stroke itself was very bad, but for Wilson, the problem was it was a perfect storm," Cooper said. "About a week after he suffered the stroke, he came down with a very bad urinary infection, a high fever, and that really debilitated him and was life-threatening. So, it's that combination that just did him in."

For the last year and a half of his term, Wilson was not a fully functioning president. The First Lady, Edith Bolling Galt Wilson, let nothing come out about his health. It took three months before an attending physician let slip the gravity of the situation.

Even as the rumor mill swirled, Edith Wilson and others staged elaborate set-ups to make it seem like the president was much less impaired than he was.

Meanwhile, Edith Wilson and others began running a shadow government to lead the country under the guise of the president.

"There's never a good time for something like this to happen, but this was a particularly bad time because this was when the Senate was going to come to its vote on consent to the treaty," Cooper said.

The Senate did not ratify the peace treaty, and the U.S. did not join the League of Nations.

Fifty years later, Congress ratified the 25th Amendment, allowing for a president to be removed from office if they're incapable of governing. Wilson was not the first president to be incapacitated — Dwight Eisenhower suffered a heart attack, in Denver in fact, and Franklin Roosevelt was in poor health for his last year or so as president.

Wilson's stroke left him not only physically impaired, but also mentally impaired.

"I think the worst problem of presidential ability is not physical disability, such as Wilson's or Franklin Roosevelt's, for that matter, but it's mental instability, emotional instability. And one of the worst aspects to the stroke on Wilson was to impair his judgment," Cooper said. "His mind was clear. He could think just as well as before. But he didn't have the emotional balance, the kind of things that go into judgment."

A century later, it's much more difficult for presidents to hide themselves or their health issues from the press. Cooper says that, in a way, is protection for the public from a shadow presidency happening again.