Sebastian, an 8-year-old from Denver, couldn’t take one more day at home.

“I would just always be sitting on the couch doing nothing,” he said during recess about the long five months of not being inside a classroom. “I was so bored ... sometimes helping my mom with her work.”

Sebastian would help his mom clean houses. He said some of the houses were big, with second floors and balconies.

It was hard work, and sometimes he wished they had a house like that.

“I was excited coming to school,” he said in new black school slacks and gleaming white shoes.

Westminster Public Schools was one of the few metro Denver districts to go fully back in-person in August. But school in a pandemic would be unlike anything he and his teacher Renea Sutton have seen before.

CPR is following their classroom, Room 132 at Josephine Hodgkins Leadership Academy, to see what life is like in schools this fall. In these unprecedented times, the question for Sutton, Sebastian and his classmates in the first few days became: Can you build a community in the midst of the complicated pandemic logistics?

Why open in person at all?

Over the summer, while other districts were going back and forth, shifting plans from reopening in-person to remote to a mixture of both, Westminster Public Schools was resolute that it would open its doors in the fall for families who wanted it. Others could sign up for the district’s virtual academy.

In a letter to the Tri-County Health Department that accompanied its reopening plan, Superintendent Pamela Swanson, named Colorado’s 2020 Superintendent of the Year, spoke of the challenges that the isolation forced by COVID-19 has on some children.

“Many of our students are vulnerable at home: victims of physical or sexual abuse, at risk of depression and suicidal thoughts, at risk of losing their home due to loss of familial income, at risk of losing their future due to increasingly large gaps in their education.

“Our parents and students need hope, we need to help them navigate the challenges and help them see wonder in life again. In order to do this, our doors must be open.”

The spring's school closures meant that by the time they enter classrooms in the fall, students may return with 70 percent of the reading level they’d typically be at and 50 percent of typical math levels, according to research by the Northwest Evaluation Association, a research and learning assessment non-profit. The longer students — especially low-income students — are out of in-person learning, the larger the existing achievement gap is expected to grow between them and their wealthier peers.

“We were quite worried about that academic slide,” Swanson said. “Our main concern with not bringing kids back or even postponing and starting up school even later was that we would widen the achievement gap.”

In Westminster Public Schools, nearly 80 percent of students qualify for federal free and reduced-price lunch, three-quarters are Hispanic, and 41 percent are English language learners.

Throughout a long summer of fluctuating COVID-19 rates and growing anxiety among the public, Swanson remained steadfast in her desire to open schools.

Teachers like Renea Sutton were surprised and a little nervous at first when she learned they were reopening. She has a 93-year-old grandmother she cares for once a week, but Sutton could keep fears about the coronavirus at bay. The future of her classroom worried her more.

“It’s just really hard to wrap my head around what this is going to look like,” she said. “All the things that we were taught that makes good teaching, you know, group work, kids working together and talking about it and doing all that. It’s like, ‘Nope, now you can't do that.’”

But Sutton likes challenges. That’s why she left the Postal Service years ago and moved into teaching — to do something that was always different.

“Teaching — boy, did I get that! There's always some challenge. This ... this is big. I think the unknowns are huge and we have ideas of how we're going to handle it, but we're still not sure how that's going to look, you know?" she said. "We're going to have to check and adjust as we go.”

On Aug. 20, the door opened to Sutton’s Room 132 at Josephine Hodgkins Leadership Academy.

Ten kids showed up on the first day. The rest signed up for the district’s virtual instruction or are still wavering about coming into the classroom.

She knows her students have been pretty isolated for five months. Throughout the day she peppers them with questions about how they’re doing and how the spring was.

“I didn’t mind it but I’m kind of glad to be here again, ‘cause I kind of missed being here,” an 8-year-old named Owen told her. “I missed my friends and my teacher.”

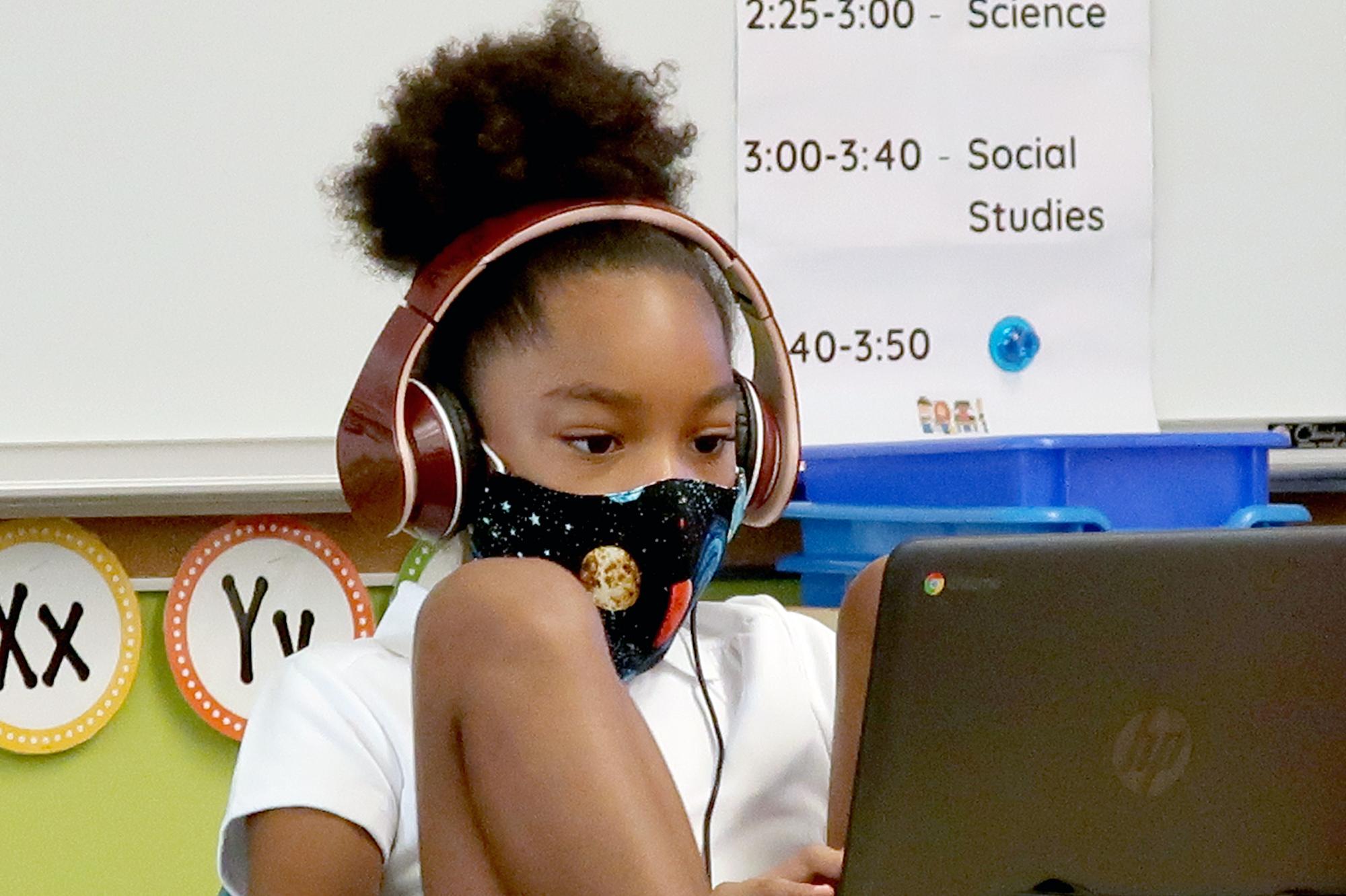

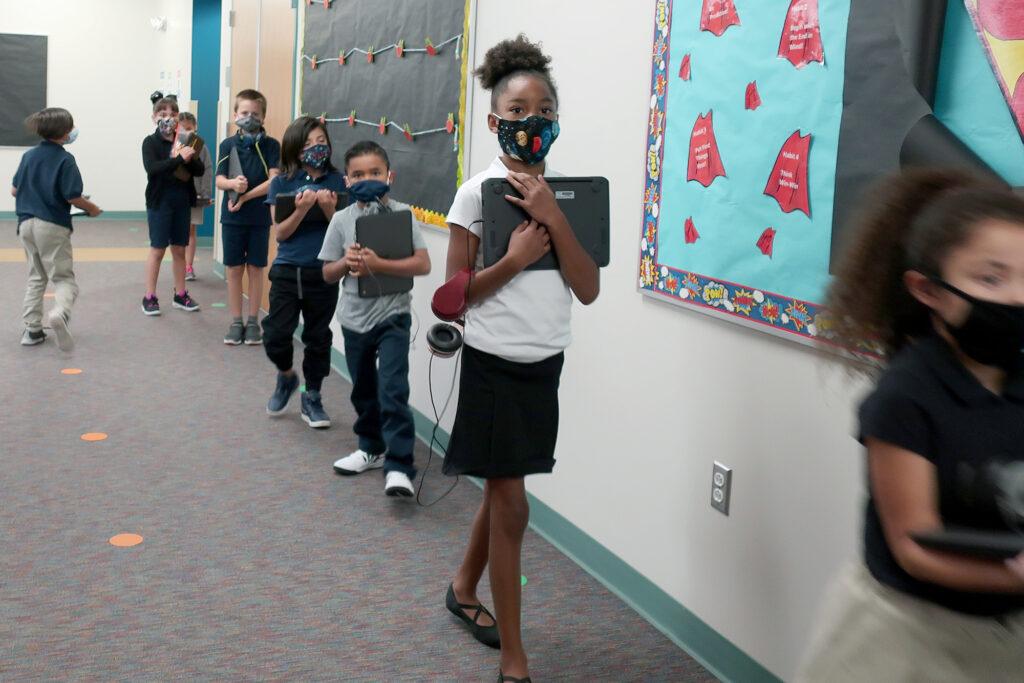

There’s also a lot of logistics to go through: No drinking fountains, no eating in the cafeteria, no balls on the field, no parents in the building, everyone wears masks, two students to a table and Mrs. Sutton takes your temperature every morning.

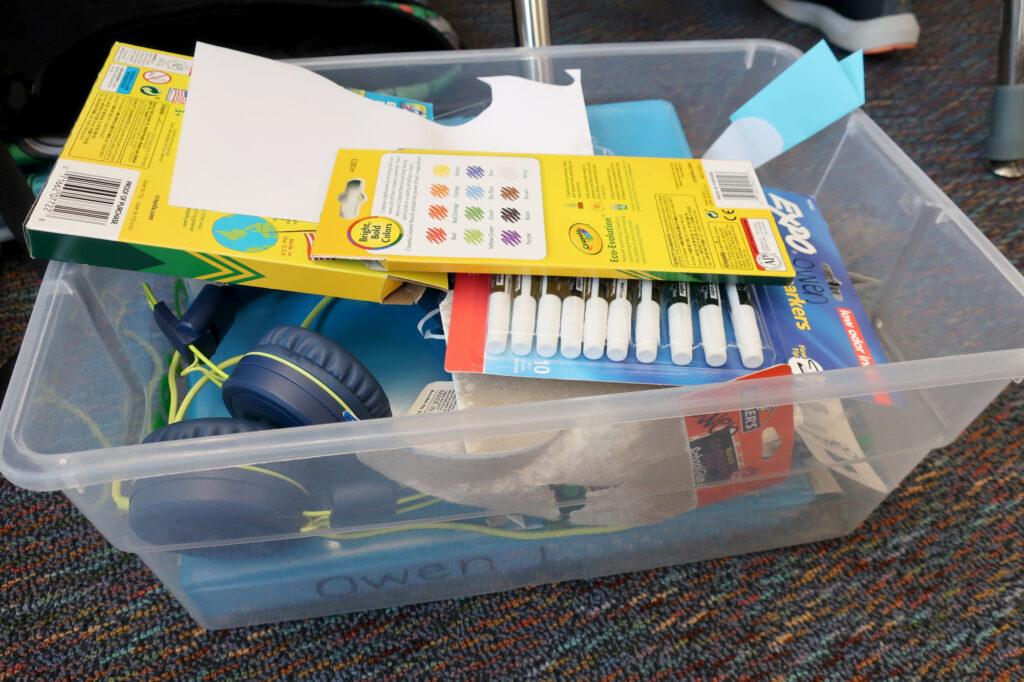

Each student has their own plastic tote, stuffed with supplies. No sharing of pencils and scissors.

“We don’t go back and forth to our cubbies in the day,” Sutton called out to the kids.

She is a stickler for organization. She has come up with little games to manage the new routine, including one to prevent the perpetual problem of the lost pencil.

“It’s called ‘Pencil Wars,’” she explained. “You have five pencils for the week that are sharpened. You will sharpen them now because we can’t have a pencil sharpener.”

If their five pencils are in shape by Friday, they can pick a small prize.

She also does a lot of ice-breaker games with the kids to help them get to know each other. She’s big on teaching kids to really listen to each other.

“Kimberly, what did Owen say his favorite color was?”

“Owen’s favorite color was ... was ... I couldn’t really hear it.”

It’s a little harder to hear with masks on.

“So we have this thing with social distance but then we’re also trying to hear, but then we have a mask,” said Sutton, explaining the acoustics of wearing a mask. When a girl’s mask breaks, Sutton rolls with the punches and teaches them the wonders of duct tape.

“I’ve done all kinds of things with duct tape,” she told the class and student Owen reminds her when she fixed his brother’s glasses with duct tape.

It’s hard to capture what she’s teaching in these moments in a test score. Instead, it’s these little hurdles, the stuff of life, and the way to come up with creative solutions to them, that Sutton wants to impart to her kids this year.

What to do when your face mask breaks? Duct tape.

What to do when you can’t have a soccer ball on the field anymore? Make up a game.

What to do when your mom is so tired it makes you really worried about her? Talk with your classmates about what you can do to help her.

What to do when you’re afraid someone will laugh at you? Talk with your classmates and teacher about how laughing at someone makes them feel.

By the beginning of the second week in school, Sutton is thinking ahead to the rest of the year.

A teacher at the school tested positive for COVID-19, sending more than 100 kids in the upper grades back home to remote learning. Sutton wants her students to learn to troubleshoot on the computer in case they, too, have to go back to remote learning.

They’re not excited about that idea.

“Being at home and doing the work on the computer felt just way harder than doing it at school,” said Alejandro. At school, you can write with a pencil and paper. “It takes almost all day to get all your work done on the computer at home.”

Others say it was easy to get distracted.

One of the biggest reasons young kids struggle with remote learning, besides the fact that they like to move, talk, and hug their friends, is that many don’t have solid computer skills, or the typing skills, to get stuff done efficiently.

There are 12 kids in Sutton’s class now, a couple more than the first day. The small numbers are an unexpected boon to opening in-person.

“I feel like that because the numbers are smaller, that some of what I would do in groups is possible because I can keep that distance,” she said. “But if I had another 10, I'm not so sure I could have them ‘turn and talk.’”

The small numbers also mean she doesn’t have as many asking for help when they begin to really struggle. One girl has a broken head jack stuck in her computer and can’t hear. So Sutton plays a lesson about “germs” out loud so she can hear.

“Coronavirus is the newest bad guy on the scene,” boomed a British narrator. “It’s really small but it has some superpowers that make it tough to fight. But that doesn’t mean we can’t beat it!”

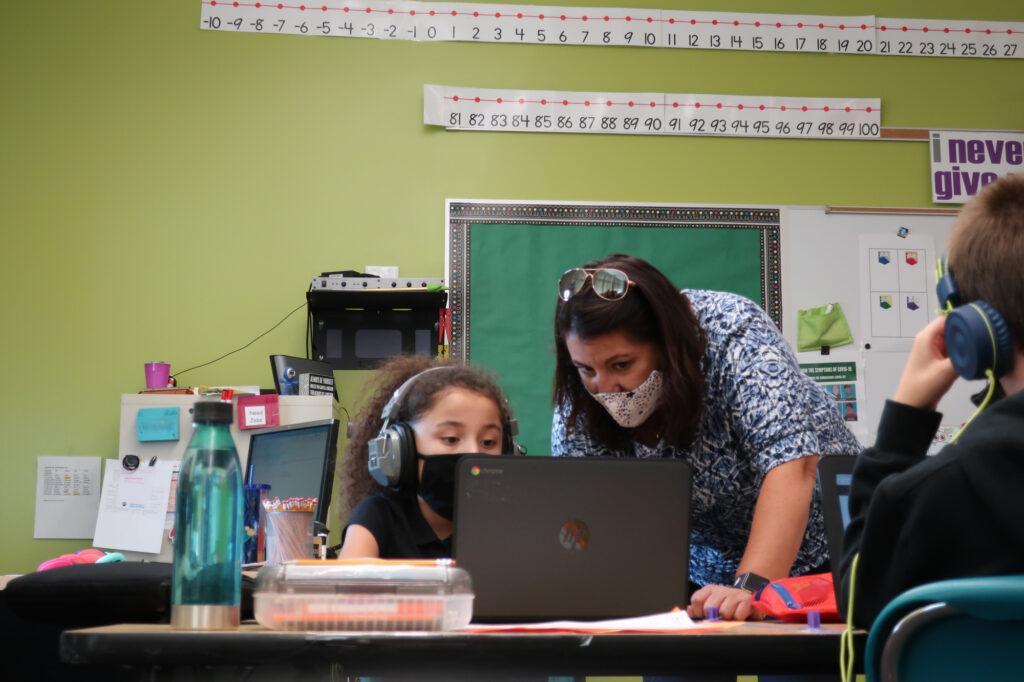

Sutton explains how lessons work on a computer, where questions will be and how to ‘post’ their answers — a confusing concept for some. The program they’re using has been updated over the summer and it’s all new to everyone.

“They’ve been out for such a long period of time,” Sutton said. “But then on top of that, what they do know about school has changed on them.”

Some kids’ computers stall. Sutton explains the concept of rebooting. You don’t quit, she said.

“Shut down your computer, start it back up.”

Sutton goes from child to child explaining the process of cutting and pasting. When students struggle to remember the lesson in order to answer the teaching program’s questions, Sutton asks another student, Azriel, to explain how he took notes as he listened and reminds them they can click and the computer will play the lesson on germs again. It’s hard to imagine her fielding computer questions from 25 kids or helping these 12 troubleshoot remotely.

But Sutton is calm and steady. She’s a problem solver and wants her students to be too.

Building a safe community is a huge priority of Sutton’s.

She’s trying to figure out how to have her daily meeting where everyone has a chance to talk about their feelings, but it’s hard with social distancing. So she starts by having them read a story about bullying and telling them her big rule:

“We do not laugh at anybody,” she said. “We all are different. Some of us are really good readers. Some of us may struggle with reading.”

When someone laughs at a classmate, she said, it makes them not want to try. She tells them, that’s why they’re here: to try and to learn.

Some kids are halting as they read. Others have more confidence.

They discuss the article on bullying. Sutton told her own story of being bullied as a child, of a girl saying she’d beat Sutton up unless she shared her Barbie dolls. The scary situation went on for a while and her parents didn’t know about it.

The kids listen with rapt attention.

Then the kids read the rest of the article silently for 15 minutes. That’s when Sutton can see who is absorbed in reading, and who is having problems staying focused. One boy puts his head on the desk. Another two prop up their magazines — kinda hiding, or quietly peak over the top to check if Sutton is watching. She is.

In the end, she asked them how they felt about it — starting with the boy who put his head on the desk.

“It was, like, peaceful,” he said.

“Peaceful?”

“Like it was quiet.”

“OK, quiet, I can see that. You know sometimes having some quiet time is nice.”

One girl said she had a headache but after silent reading her head was calm. Sutton told them about her own struggles concentrating.

“I can’t read when it’s noisy.”

“Me either!” shouted Owen.

“Remember, we’re here to learn, we’re here to get better right? We’re going to make mistakes,” she said gently.

Sutton told them she wants to help them understand what kind of learner they are. It will be a while before Sutton can really assess where the students are academically, to see if there are big gaps, and what needs to be done about them.

But overall, she’s impressed with what she sees.

“I was really surprised,” she said. “Their writing looked pretty good. I was seeing some pretty decent sentences. I was like, wow, that's pretty impressive.”

At the end of a long day with the rest of the year looming, Sutton is hopeful.

“I think just getting back into the groove of things, it felt hopeful,” she said. “I told them that this morning, ‘It's so great to see your faces. Even if it's this much, just a little, instead of a little box, I said, it's a different feel.”

She hopes they can keep this up.