It was Reynaldo Hernandez’s first election. The 18-year-old was finally old enough to vote, and he proudly sent back his mail ballot in this year’s June primary.

It was rejected — one of 25,263 that went uncounted in June by Colorado elections officials. That’s about 1.6 percent of the total votes cast.

Most of those, like Hernandez’s, likely contained the voter’s signature but, in the opinion of election judges, didn’t match closely enough. Voters were given a chance to cure, or fix, the ballot, but most did not.

While Republicans have raised alarms about the potential for fraud in mail balloting without finding much evidence and Democrats have focused on fighting any effort to suppress the vote, elections officials have come to accept that thousands of people may be disenfranchised in each mail ballot election when their valid votes are rejected and voters fail to fix them.

From 2016 to today, Colorado clerks have discarded more than 100,000 ballots in statewide elections. But little attention has been paid to the state’s lost votes because — so far — they have never amounted to enough ballots to swing an election from one statewide candidate to another.

With a deeply divided electorate in the state and nation, that could change in an instant.

Just ask Floridians, where the 2000 U.S. presidential election was decided by just 537 votes after a frantic post-election search by campaigns and counties for valid but uncounted votes among ballots that seemingly contained no choice for president.

A two-month CPR News review of Colorado’s seven-year history with statewide voting from home found that a combination of voter errors, a variety of signature examination techniques and equipment, and language barriers have contributed to the discarded valid votes over the years.

Among the findings:

- The rejections happen at considerably different rates from county to county, with disenfranchisement seemingly dependent on a number of variables, including the use of signature review software, the training of verifiers, or the opinions of election review judges.

- Counties with populations of racial and ethnic minority residents above the state average account for some of the state’s highest rates of rejected ballots. Despite the state’s growing diverse population, most counties send instructions for fixing a rejected ballot only in English.

- Ballots cast by younger voters are discarded at a disproportionate rate, partly thanks to balky signature pads at driver’s license offices. Those record awkwardly scrawled handwriting that doesn’t match a later ink and paper signature on a ballot envelope.

- Disparities in budgets and equipment between counties can lead to wide differences in rejection rates. Those where signatures are first reviewed by machines tend to record far more rejections overall.

- Even when offered the opportunity, few voters fix their signatures or add a missing signature, and political campaigns can often be the biggest driver of cures if they are motivated enough by a close race to chase voters down.

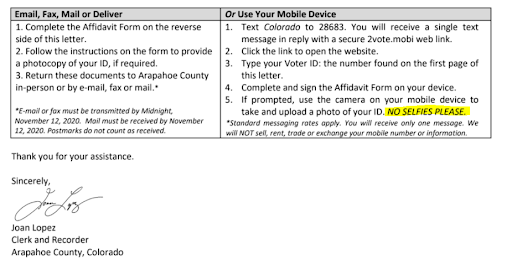

Hernandez was notified his vote was in jeopardy by a letter from the Arapahoe Clerk and Recorder, which offered him a chance to fix his ballot on his phone. The system called “Text to Cure” will be implemented statewide for the upcoming Nov. 3 election. But he found the instructions confusing, and when he looked at the photo they sent of the signature on his ballot envelope, he knew it was correct, so he took no further action.

Three months later, a CPR News reporter informed him his ballot, his first ever vote, was not counted.

“If I never received this call ... I would have never known,” said Hernandez. “I checked on my phone again and everything was right. So I'm not sure what the mix-up was.”

As mail ballots go out to voters starting Friday, clerks insist, with lots of evidence, that Colorado’s system works for the vast majority of voters. But if you don’t follow the instructions, and be careful with your signature, you might have to do a little extra work to make it count.

Even a 'gold standard' has its downsides.

Colorado’s vote from home election system is regularly described as the nation’s best, and it does have a lower ballot rejection rate than Washington and Oregon, other states which mail ballots to voters.

“Colorado is the gold standard,” Secretary of State Jena Griswold frequently says.

Having the time to research ballot questions and candidates as you vote with a computer and Blue Book in hand is immensely helpful. Colorado’s system also doesn’t require going to a polling place before 7 p.m. on Election Day, which can be a major inconvenience or impediment for voters across the country.

The system is especially attractive in the coronavirus era, where voting at home is clearly the safest option.

But there is a downside. Before widespread vote-by-mail, most Colorado voters went to a physical location to cast their ballot. If their identity was challenged because of a bad signature, they had a chance to fix it on the spot.

Now, the election process is happening inside people’s homes, out of view of elections officials and mistakes are leading tens of thousands of mail ballots to be rejected, uncured by the voter, and subsequently uncounted.

“Bingo. That is exactly what I've been railing against for the last almost 10 years,” said University of Florida professor Daniel Smith, a national expert on voting, and a longtime critic of vote-by-mail for all. “There's just a complete blind eye to any problems of voting by mail.”

Most of the state’s rejected-but-fixable ballots — 75 percent in the last two general elections in Colorado — are rejected for non-matching signatures. Some non-fixable reasons for rejection include putting two ballots in a single envelope, or voting more than one party’s ballot in a primary election.

And the opinions on whether a signature is a match can vary from judge to judge, table to table, and, in significant ways, from county to county.

In the 2016 general election, for instance, a voter in Adams County had a nearly three times higher likelihood of a rejected mail ballot than if they had voted just across the county line in Weld County, according to CPR’s analysis of data from the U.S. Election Assistance Commission.

A mail ballot voter in Pueblo in the 2018 general election was twice as likely to have a ballot rejected than in Douglas County in the same election.

Pueblo Clerk and Recorder Gilbert Ortiz said that might be because his signature verification machine broke down for a short time. “So we were having to do all of the signature verification by hand instead of the automatic signature verification. So that could have been why we had a bump.”

Like Ortiz, elections officials and experts CPR News contacted had difficulty pointing at a single culprit for differences from county to county, and there have been no extensive studies done of rejected ballots. Some said comparing counties was not an appropriate measure or that campaigns and voter interest can change cure rates — that there were simply too many variables and matching counties is not “apples to apples.”

Just as in most of the U.S., Colorado’s elections are managed at the county level. That means there are 64 county clerks and recorders in Colorado that range considerably in terms of staff competency, judge retention, equipment and financial resources.

When informed of high rejection rates, reactions from elections officials around Colorado ranged from mildly embarrassed to unconcerned, pointing out that rejections were only about 1 percent of ballots cast and outweighed by the higher turnout from an all-mail ballot system.

“I would argue that's the process working the way that it should,” said Matt Crane, the former Clerk and Recorder in Arapahoe County, who is now a consultant. Trust and confidence in elections is just too important, he said. “If there's any variance, then we want to flag that and give the voters an opportunity to cure.”

Voter turnout has improved since Colorado turned to voting from home. Putting presidential elections aside, when even casual voters can be highly motivated by a candidate, the percentage of active voters who turned out for the general election grew from 73.4 percent in 2010 to 74.91 percent in 2018.

But while valid votes cast at polling places were not rejected for signature discrepancies in 2010, eight years later nearly 20,000 votes, or eight-tenths of one percent of all those cast, were tossed out in the 2018 general election. Nearly 13,000 of those rejections were due to non-matching signatures.

Ballots for what will be just Colorado’s second presidential election using universal vote-from-home can be mailed to Colorado voters starting Friday, Oct. 9. In 2016, 85.66 percent of active voters participated.

- Automatic Ballot Tracking For Every Colorado Voter

- Voter Turnout In Politically Divided Pueblo May Hinge On A More Personal Campaigning Approach

- The Latino Vote Could Soon Be Key To Political Fortunes In Garfield County

- Everything You Need To Know About Voting, And Mail-In Voting, In Colorado

- Todo lo que necesitas saber sobre cómo votar por correo en Colorado

Professor Smith and his team studied Florida’s mail ballot returns and found substantial evidence that Black and Hispanic voters suffered much higher rejection rates, two to almost three times the overall rate of rejected mail ballots in Florida.

No such study has been conducted in Colorado. But CPR News found that Pueblo and Adams County, the two counties with the largest share of Hispanic population, had among the state’s highest rate of ballot rejections in the last two general elections.

In the 2020 June primary, voters with the last name “Martinez” were the most rejected in the state. It is the state’s third most popular surname, according to Ancestry.com.

“Not every vote counts in the same way,” Smith said.

The U.S. Supreme Court has regularly found that votes and voters should be treated equally, whether urban or rural and no matter what method is used for voting.

The variability in mail ballot rejection rates from election to election and county to county and from demographic group to demographic group in Colorado raises equal protection questions for Smith.

“It sure does,” he said.

But former Colorado Secretary of State Scott Gessler, a Republican and election law attorney, said giving voters the same opportunity to fix a questioned signature in every county removes any legal question about equal protection.

“I just think there's a lot of variation in the process,” said Gessler. “It's like the black art of signature verification. Once the humans get ahold of it, it can sort of be all over the map. You have a safety valve that if people's signatures are erroneously rejected, they have the opportunity to cure.”

Signatures are ‘the bottleneck of the election process.’

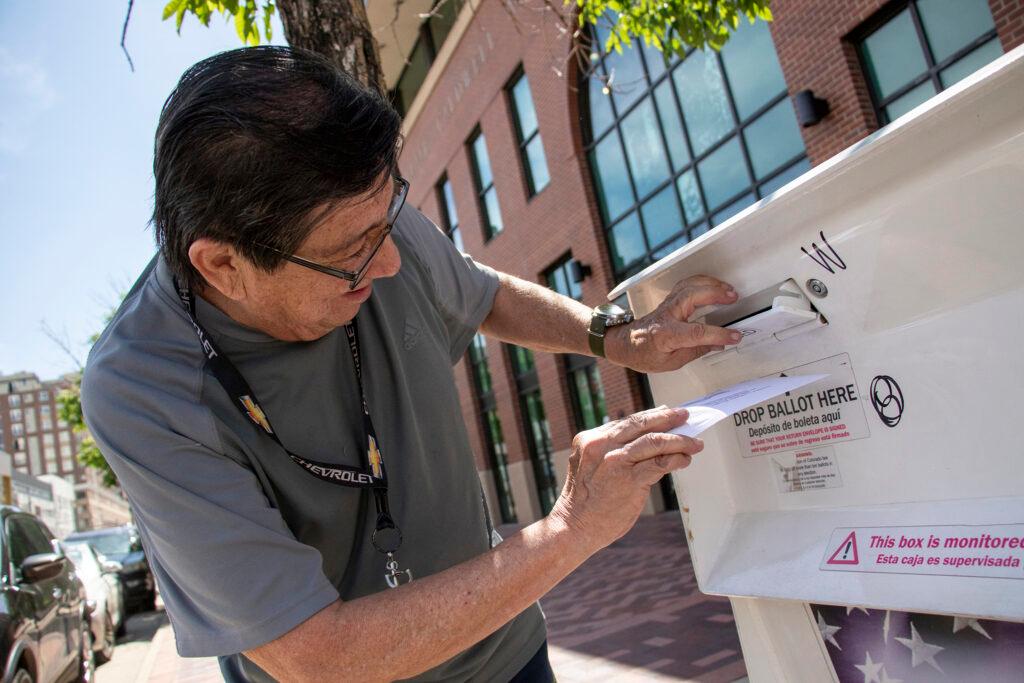

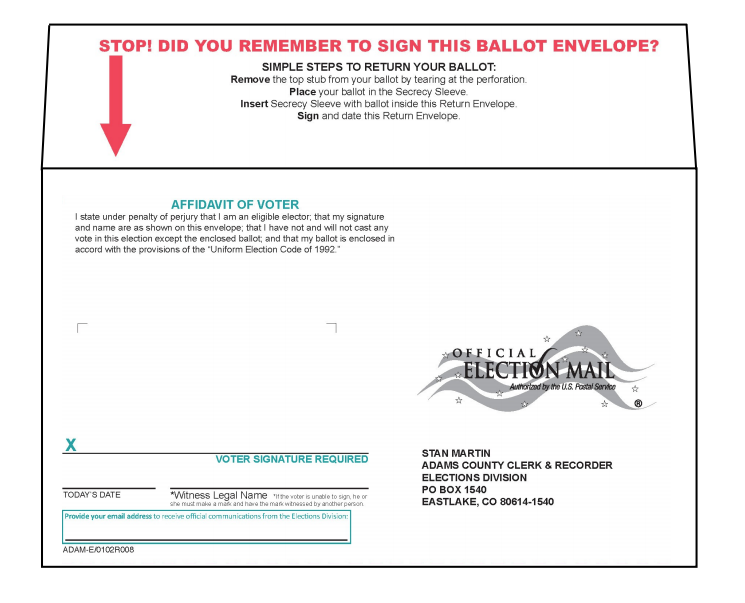

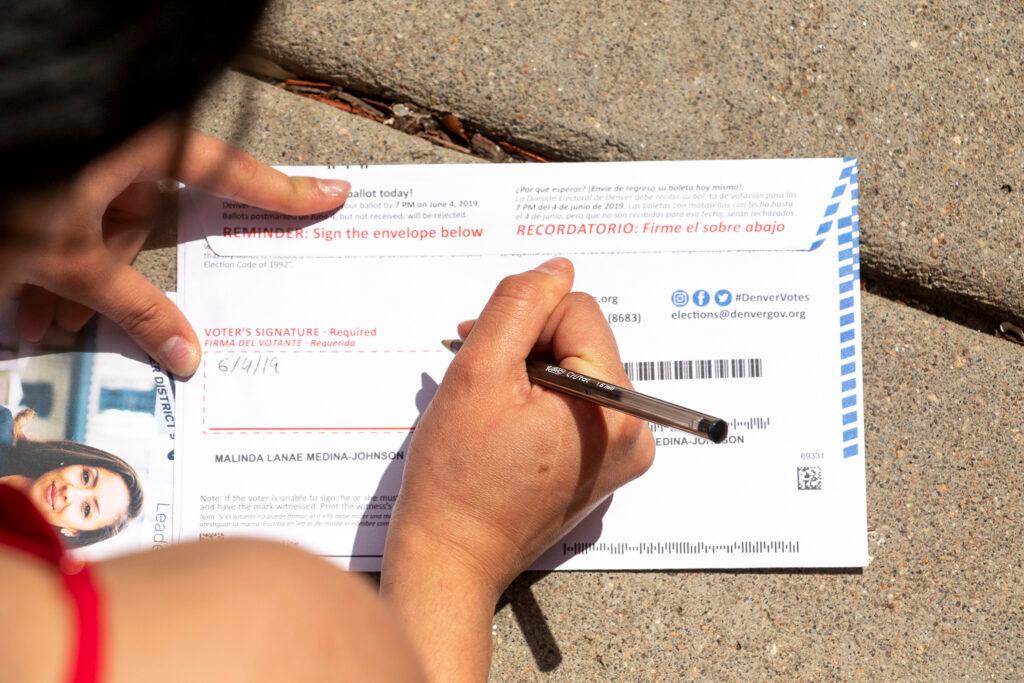

In the vote-by-mail system, a lot happens after a voter makes their choices. When done correctly, the voter puts their own — and only their own — ballot in the enclosed envelope, signs the designated spot and seals it. The ballot can then be dropped in the mail with proper postage or taken to a dropbox in their county.

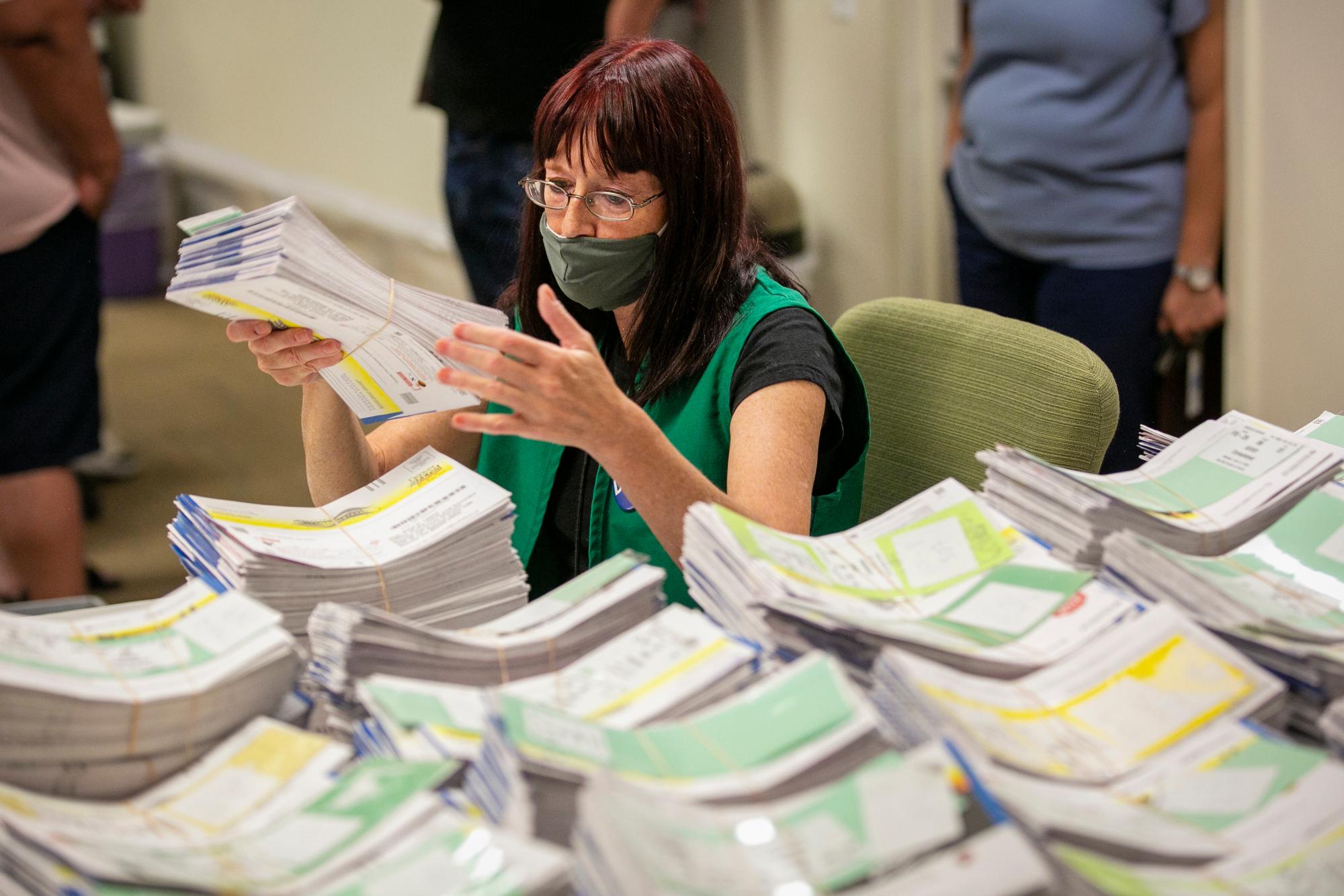

From there it makes its way into the processing center of whatever county the voter lives in. In many large counties, the first stop is a ride in the mail ballot sorting machine.

“It'll feed in over here and goes through this conveyor,” said Adams County Clerk and Recorder Josh Zygielbaum, showing off his machine, an Agilis sorter that’s the most common machine in Colorado. A camera in the sorter takes a picture of the signature. “And then that goes through cyberspace over into our signature verification room.”

In the counties that use the machine for signature verification, up to 50 percent can be accepted automatically. The machines, along with human judges, are regularly audited to be sure they’re accurate. But in counties without signature software (among them, Jefferson and Weld) human judges review every signature, slowing the process. The machine makes for a huge gain in efficiency.

“And not have to slow down processing to have judges look at it,” said Crane, the former Arapahoe Clerk. “And you have confidence that the machine is adjudicating those signatures. It's an amazing process.”

A total of 48,625 Colorado ballots were rejected for signature discrepancy alone in the last two primaries and last two general elections, and that’s anywhere between 75 to 84 percent of curable rejected ballots in those elections.

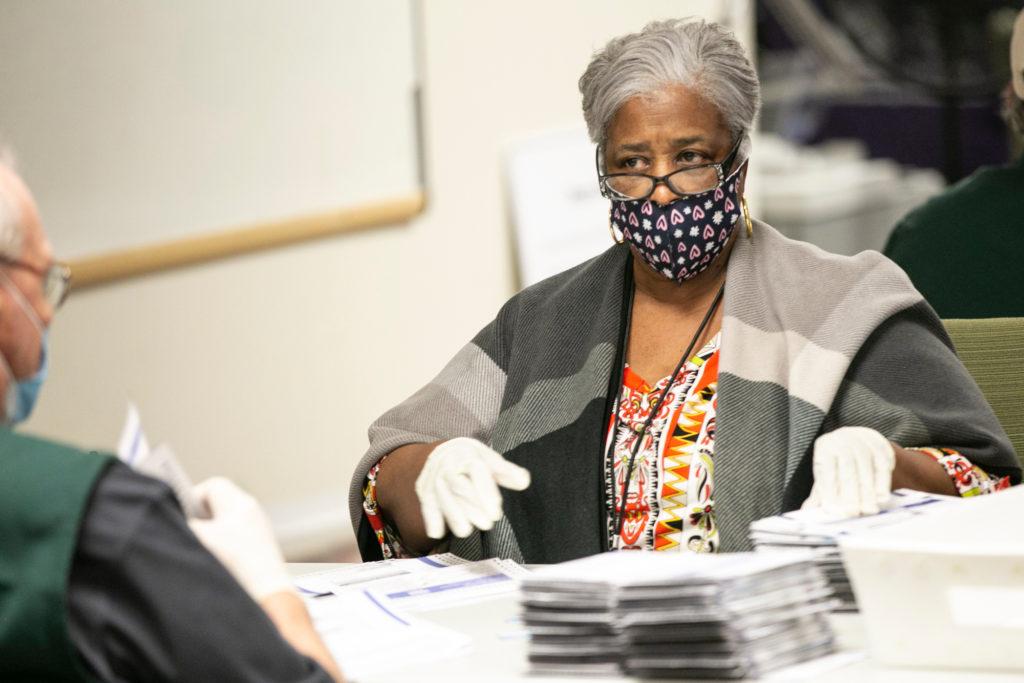

If a ballot signature is rejected by a machine it goes to an initial signature review by a trained judge. Then if rejected again the signature is reviewed by a bipartisan panel of judges. If the signature is finalized as non-matching, then a cure notice goes out to the voter to fix it. They have until eight days after the election.

Ballots that are rejected for non-matching signatures, and left un-fixed by voters, are referred to prosecutors for further investigation. Many times DA’s aren’t able to connect with the voters, and those investigations rarely result in charges.

Starting with the 2016 general election, according to state judicial records, only a total of three people have faced charges for voting while not eligible, and only 32 others have been charged with voting more than once over seven statewide elections and countless local elections — most of them for casting a ballot and signing an envelope on behalf of a relative in addition to their own.

Still, to ensure trust in the system, state law requires elections officials verify the identity of voters through signature. With more than 90 percent of votes in Colorado taking place at home, outside the watchful eye of a poll worker, the signature becomes the only way for clerks to know that the person who voted that ballot is who they say they are.

“No two writings are ever exactly alike,” Songer said. “So it's based on the premise of individuality, and that's what makes it identifiable.”

But our signatures change, even just a little, each time we put pen to paper, and they change as we age, said Mark Songer, a former FBI special agent who contracts with Denver, Arapahoe and El Paso Counties to train signature judges. And comparing that slightly different signature to one that’s on file from months or years earlier takes some expertise. The people who do the work get just a few hours of training.

Advocates for vote by mail say the signature problem is lessened with every election. Election judges and machines get better every year at identifying individual signatures. And every year voters add more signatures to their file.

“On average, signature issues are actually going down in every comparable election,” said Griswold.

She pointed to a 15 percent decline in the rate of rejected ballots for non-matching signatures from the 2016 to 2018 general election. However, the electorates are very different between those elections. 2016 was a presidential election that turned out more voters. And more younger voters in particular, which Griswold acknowledged is the hardest hit group when it comes to signature rejections.

Younger age groups have rejection rates up to 14 times higher than older voters because their signatures are evolving and they vote more infrequently and therefore have fewer signatures in their file to match against.

In the 2018 general election, for example, voters 18-24 years old had ballots rejected, uncured and uncounted for non-matching signature 2.8 percent of the time, while the largest voting bloc, 55-64-year-olds, had ballots rejected at a rate of just two-tenths of one percent.

Not only do younger voters not have a static signature. They may not have a signature at all. Many will print their name in the signature line.

“They don't teach them cursive anymore in school,” Chrissy Jackson, who supervises judges in Adams County, said with a laugh. “You'll see a lot of the younger people just printing their name.”

Many clerks told CPR News that the poor quality of signatures from the DMV, which uses digital pads, contribute to the problem. For younger voters, who register to vote when getting a driver’s license, this is often the top or only signature on file.

Many elections experts, from the Secretary of State’s office to the local clerks, have pushed for better equipment at the DMV in Colorado for years. There have also been efforts to get DMV workers to explain that this signature is important and to take care in the signing because it could be used to match the signature on a ballot.

Carly Koppes, the Clerk in Weld County, says the Department of Revenue which manages that part of the process is aware of the problem and has a plan to eventually upgrade the pads. But that won’t be rolled out in time for this election.

“We're definitely probably going to see a higher rejection rate because I don't know about you, but my signature on a (digital) pad is nowhere close to what my actual signature is. It is horrible,” said Koppes.

Another possible source of signature confusion: Voter registration drives.

“If somebody stops you down on the 16th Street Mall as you're going to work or wherever you're gonna not be as careful with your signatures,” said Crane, the former Clerk in Arapahoe. “And so when you're taking your time, signing your ballot, there's going to be a difference.”

Griswold said the state will roll out a mobile device curing system called “TXT2cure” this election. It has received mixed reviews in counties that have used it.

Arapahoe County reported significant increases in younger voters curing their ballots. But some counties have reported that the text system actually generates new unreadable signatures and worthless responses of voters taking selfies to confirm voter ID. Rural counties have expressed concerns about a lack of stable internet and cell service limiting their use of the system.

The mobile system displays a picture of the voter’s envelope signature and asks if it’s correct. The voter then signs with their finger on the phone (which clerks admit is highly unlikely to match a pen and paper signature). Then the voter must upload a picture of their driver's license or other identification.

So many voters in Arapahoe County uploaded selfies rather than their ID, that the county added specific language to cure letters: “NO SELFIES PLEASE.”

And voters like Reynaldo Hernandez, who received a text through the Arapahoe system, can easily misunderstand the process and fail to correct any discrepancy.

But the problem really starts, when it comes to signature mismatches, before a voter ever realizes something is wrong: When the signature is flagged as not matching in the first place.

It’s here that systems in Colorado can diverge significantly by county.

“It's the bottleneck of the election process,” admitted Gilbert Ortiz, the long time Clerk and Recorder in Pueblo County. “So there's a lot of stress on (signature judges), because everybody in the whole operation is waiting for them to get the signature verification done so they can start counting the ballots.”

“Sometimes we have to move (signature judges) in and out of positions because they're burnt out,” said Ortiz. “You can imagine going through 40 percent or 50 percent of 70,000 ballots, it's going to be pretty tough on you.”

The signature verification machines that many counties employ are not perfect. Human judges, while trained to match signatures by experts, also can’t catch every valid signature, especially if there are a limited number of signatures on file to compare it against.

Still, all potential rejections must go through several sets of human eyes before a final rejection, and Colorado not only has statewide standards, but many counties contract with outside experts to supplement training, like Songer, the former FBI agent.

“The first thing I tell them is, ‘Listen, you're getting one-hour instruction here. You know, this doesn't make you an expert. What I'm trying to do is teach you the fundamental basics of what we as handwriting experts look at,’” said Songer.

Songer, though, is encouraged to see many of the same judges return year after year because the more experienced they are the better.

“They're making a big decision, right?” said Songer. “We want to make sure that every vote counts, and that if there's an issue with a signature that they're properly evaluating them and making the right decision. So I think there's a lot of pressure on a newer judge.”

Koppes, the Weld County Clerk and Recorder, said that she praises her experienced judges so much they’re probably tired of hearing it from her.

“They are our number one biggest defense against election fraud,” she said. “Your newer judges, they're going to be like, ‘OK, I've got to criticize absolutely every little wrongdoing.’ And I can tell you from this morning to probably right now, my signature is going to be different and that's just within a day.”

Colorado elections experts admit it’s an inexact science, with humans at its center, so mistakes will be made, but, again, it’s crucial to note that voters are given time and opportunity to cure the discrepancy and have their vote counted, unlike in states like Wisconsin.

“At least in our state you can cure your ballot. Other states, you’re just out of luck and they don’t even tell you,” said Peg Perl, the current elections director in Arapahoe County. Voters have up until eight days after the election. That’s November 12th this year. Perl says they work hard to get the cure notices out fast, giving a voter potentially several weeks to fix an initially rejected ballot. “Because we want there to at least be the chance that people can fit it into their normal life.”

But, despite all the tools and time, few voters actually take the time to fix the problem. County clerks report cure rates anywhere from 20 to 30 percent. (Some counties report slightly higher cure rates in presidential elections because interest is so much higher.)

Many voters who CPR News contacted, who did not cure their ballot, talked about busy lives filled with work and school as impediments to fixing a ballot they already took the time to research, fill out, and send in.

But officials caution that no election model is perfect.

“Whichever style of election model that you do, there's always going to be something,” said Koppes in Weld County. “So with mail ballot, you're going to have signature rejection. With precinct polling, you're going to have some people are just not going to be able to make it home,” in time to vote in person.

No two large neighboring counties have a larger difference in rejected ballots than Adams and Weld County.

Weld has among the state’s lowest rates of rejected signatures and Adams has among the highest. And the counties offer a case study in how different systems and demographics can lead to radically different outcomes.

Adams County is among the most diverse in Colorado, with 40 percent of the population identifying as Hispanic, according to Census data. That’s far more Hispanic residents than any other metro county, 10 percentage points higher than Weld County.

But it’s more than just a large Hispanic population. In his office, the Adams Clerk, Josh Zygielbaum, has a whiteboard filled with the dozens of languages that are spoken in his county. Part of Adams dips down into North Aurora, which is as diverse as just about anywhere in Colorado, with refugees and immigrants from all over the world. “Our top five languages spoken in Adams County are English, Spanish, Hmong, Russian, and American sign language,” said Zygielbaum.

Adams County has double the number of foreign-born residents as Weld County, according to Census data. So it’s not that crazy that they would have a more difficult time adjusting to a Colorado election system that hinges on a signature.

“Especially for somebody who's immigrated here, some people come from countries where they don't use last names, and they may not use signatures,” said Zygielbaum, who says he’s launched new efforts to translate materials into multiple languages, ballot drop box locations and community liaisons.

But it goes beyond demographics.

Weld County and Adams County are also separated by technology. Weld County doesn’t use signature verification software or a machine sorter that can cost a quarter of a million dollars.

“Honestly, it's a big investment,” said Koppes, the Weld Clerk. “That's a good chunk of change. Here in Weld County, we're pretty fiscally conservative.” Though she says there are plans to use a sorting machine it in future elections.

But the two large counties with the lowest rejection rates in the 2018 general election, Jefferson and Weld County, are the only two counties that don’t use signature verification software. And Koppes said that could be a reason she has fewer rejected ballots than Adams County.

“I'm not uploading into the state system a whole bunch of rejects that have to go on to my signature board, because I'm not having that automatic machine.”

Advocates for the computer argue that the machine is catching many signatures that an all-human process might not.

“I do think that the machine is a better look at it,” said Crane, the former clerk in Arapahoe County. “The machine doesn't get tired on election night. The machine doesn't have sight issues.”

But if the machine is kicking out more signatures, in some cases because of bad DMV signatures on file, at the same time voter fraud is extraordinarily rare, it raises questions as to whether the efficiency of the machine is pushing tens of thousands of people into a cure process unnecessarily. One that the vast majority of voters never complete.

Mikell Yamada, a Denver voter who had his ballot rejected in the 2018 general election, said he knows his “scribble” of a signature was why his ballot was flagged.

He was sure he cured his ballot, but Denver records show he didn’t. When informed by CPR News that his vote in 2018 didn’t count, Yamada was surprised. And he said he’d have to change things up to make sure his vote counted for this upcoming election.

“I have to go vote in person,” he said. “It's inconvenient for me, but given the state of my country, like a little inconvenience doesn't seem so bad right now.”

CPR News Audience Editor Jim Hill contributed to this report.