The first incarnation of passenger rail service along the Front Range could be a modest one: two to six round trips a day between Fort Collins and Colorado Springs on trains traveling an average of 45 miles per hour mostly on existing freight rail tracks.

That could cost $1.5 billion to $2.5 billion, according to a draft report presented to the Front Range Passenger Rail Commission on Friday. A second phase would add service between Colorado Springs and Pueblo at a cost of $200 million to $300 million.

“This approach allows for a starter service and ultimately supports the rail commission's longer-term vision,” Carla Perez, senior strategic consultant with global design firm HDR, told the commission. “But it's really a way of getting this program going.”

An adjustment of Amtrak’s Southwest Chief under discussion now that would add service to Pueblo could connect some Eastern Plains communities and Trinidad to the Front Range line as well.

The commission’s longer-term vision is for a much faster, more frequent, and costlier line stretching from Cheyenne, Wyoming to Trinidad and perhaps points south. Speeds would top out at 90 to 110 miles per hour on newly laid track, trains would run every 30 minutes at peak times, and it all could cost between $7.8 billion to $14.2 billion.

"That number is something that probably we won't be looking at in terms of seeing on the ground for probably 20 to 30 years from now,” said Randy Grauberger, director of the rail project. “But it's certainly the long-term vision, when the population of Colorado supports that and we have the money available."

The commission still needs to determine a funding stream for the first version of the line, too. One possibility is Amtrak, which has made it clear in recent months that it would like to invest billions into a new Front Range line. Another option is a new tax district that would cover the Front Range. That would require legislative action and then a vote of the district’s members.

In the meantime, the commission’s consultant firm HDR will finalize its report with recommended routes and rough timelines by the end of the year.

Then, the commission will work with the Federal Railroad Administration to develop a service plan and more detailed ridership modeling. CDOT’s initial projections showed nearly 3 million riders per year by 2045, but that assumed 25 round trips per day — far more than the modest service proposed now.

Also needed is a years-long environmental review that could cost millions of dollars and would further nail down design and costs. Grauberger said a combination of federal and local money could pay for that. His best guess is that work could wrap up in 2024, under the best circumstances, and service could start five to 10 years from now, at the soonest.

“This stuff doesn’t happen overnight,” Grauberger said, but added, “we’ve made a lot of progress.”

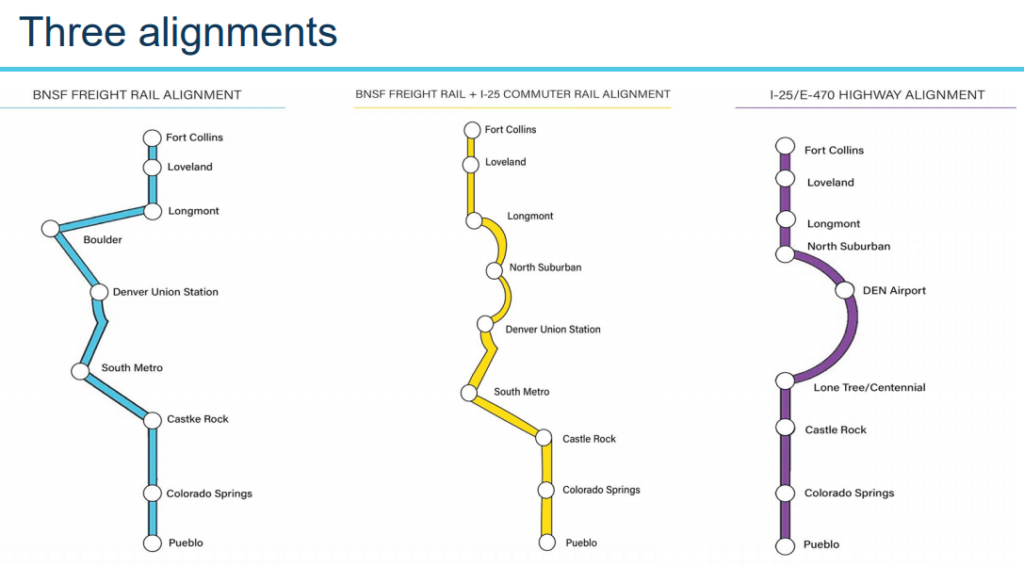

The environmental study would also identify a preferred route, or some combination, of the three under consideration now.

The HDR team said they found all three to be feasible, and recommended the commission select the option that follows existing Burlington Northern Santa Fe tracks through Boulder and Longmont as its preferred route.

That would fit in well with the Regional Transportation District’s own plans to complete a long-promised extension of the B Line through Boulder and Longmont. Cost estimates for a full build-out of that now are $1.5 billion to $1.7 billion, which have pushed the expected completion date for that to 2050.

While existing speedy bus service on U.S. 36 already serves the corridor well and, based on ridership projections, has suppressed the need for the B Line, political leaders in the area are still pushing RTD to pursue the project. Some RTD board members said at a meeting Tuesday that the Front Range project represents an opportunity to collaborate.

"This is such an exciting prospect,” Judy Lubow, who represents Longmont, said toward the tail end of a four-hour-long meeting.

Vince Buzek, who represents northern suburbs including Westminster, said while the Front Range Passenger Rail line may one day serve Boulder and Longmont, it wouldn’t serve smaller communities along the way like Broomfield and Louisville where RTD had planned stations.

"I don't see this being a replacement for our Northwest Rail obligations,” Buzek said. “It's worrisome. I don't want to conflate the two."

But it’s quite possible that a parallel Front Range Passenger Rail line could help RTD reduce the costs for its B Line. A significant impediment for RTD came in 2011 when BNSF Railway shocked the agency by setting a cost of $535 million to use its rail line. If the Front Range project can acquire usage rights, it’s possible RTD could use the track too without paying full freight.

RTD would likely pitch in and help pay for that and other needed improvements, said the agency’s assistant general manager for planning and development Bill Van Meter.

"The concept would be a potential collaboration benefitting both projects,” he told RTD’s board.

Separately, RTD is considering rush-hour only service on the B Line. But that would cost more than $700 million, and the agency is in the midst of mass layoffs and an ongoing budget crunch. Board member Bob Broom of Aurora said it might be time to think about trying to drum up new revenue.

"We need to discuss as a board, at some point, are we going to ask voters for an additional sales tax to finish up FasTracks?” he asked, referencing the 2004 voter-approved project. "We owe it to the voters to try to get this done because they approved it."