The number of people who died in Colorado’s state prisons climbed 58 percent in 2020 — from 45 to 71 people over a single year — largely due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Despite conditions that proved fatal, none of those 71 people qualified for early release under the seldom-used Special Needs Parole — a state law that requires officials to evaluate whether inmates who suffer from chronic, permanent, irreversible conditions that require “costly” care, or are incapacitated.

All of them died in custody.

The Department of Corrections declined to discuss individual cases or say whether any of those who died should have been considered for early release either before contracting COVID-19 or in order to receive treatment for it.

“The Department of Corrections has conducted a full review of every facility and every incarcerated individual age 55 and over to determine whether or not they met the criteria to be considered for special needs parole,” said DOC spokeswoman Annie Skinner, in a statement.

Advocates disagree, saying that DOC has shirked its responsibility under state law because they aren’t catching ailing inmates suffering from chronic, permanent, irreversible conditions — often before they die.

The raw numbers, they point out, are telling.

In 2019, the parole board considered releasing 53 people, out of about 19,000 prisoners at that time, but only ended up granting three special needs releases.

In 2020, with a pandemic raging that sickened more than 8,000 inmates, the parole board considered releasing 118 people, but only moved forward with 16.

“The bottom line is people are needlessly dying in prison. I don’t think it gets much worse than that,” said Christie Donner, executive director of the Colorado Criminal Justice Reform Coalition. “The law clearly says the Department of Corrections is responsible for identifying sick people who meet criteria and they’re not doing that. And they can’t have the onus on the inmate because a lot of these folks are too sick or mentally ill to complete some worksheet to start the process.”

In 2020, at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, Gov. Jared Polis gave Corrections officials the power to release additional people through an executive order aimed at alleviating crowding inside the state’s prisons. As they worked quickly to carry out that order, Corrections officials only considered people convicted of so-called “victimless” crimes.

As with all parole considerations, the board weighs whether the person is likely a public safety risk.

Officials released 166 people before Polis let the order expire last May.

‘I feel helpless’

While current state law puts the onus on the Department of Corrections to identify inmates with dementia or severe chronic illness, inmates are also allowed to apply for special needs parole. Private attorneys and family members often write letters to the state’s parole board asking them to consider inmates for release.

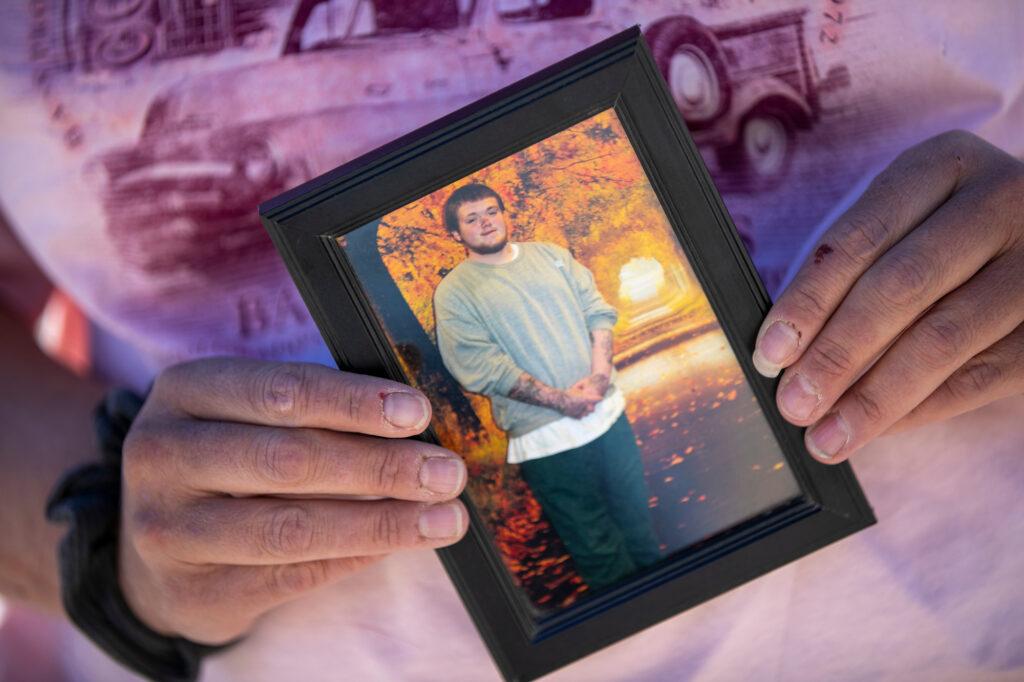

That includes Kim White.

White’s 23-year-old son, Dustin Cole Logan, was convicted in 2017 for aiding in a string of armed robberies in Colorado Springs. A store clerk was killed in the spree, though Logan wasn’t involved in the murder, according to records.

Logan has Guillain-Barre Syndrome, an auto-immune disease, and an IQ of 69 — below the normal range of 85 to 115. A 2015 assessment made by Children’s Hospital said Logan has the skills of an 8-year-old.

White said her son never had friends in school due to his disabilities but when he was 18 got caught up with a bad crowd out of sheer excitement that others would want to hang out with him. He was the only person in a group of juveniles with a driver’s license and, she said, the other kids took advantage of him.

“They claimed to have been his friends. With his disability, he didn’t know any better,” White said. “He thought, I finally have some friends I could hang out with.”

Logan had no previous criminal record before the robberies and used to spend his time helping his mom take care of two of his grandparents both of whom are also disabled, White said.

Then-Colorado Springs District Attorney Dan May submitted a letter to the Department of Corrections in October 2020 taking no position on Logan’s special needs parole application. May noted that Logan was so cooperative with law enforcement during the investigation that he would have been considered for the youthful offender system. But Logan’s intellectual disability and need for extra physical support prevented that.

So Logan entered prison at the Sterling Correctional Facility at 19 years old. He will be eligible for parole in 2023.

Logan contracted COVID-19 in the early spring of 2020, his mother said, and was sick for a few weeks. More worrisome for her, though, is that after the worst symptoms passed, Logan developed a tremor so egregious that some days he can’t get out of bed. He used to take medicine for neurological pain connected to the Guillain-Barre — but in the prison system, he’s only offered Tylenol or ibuprofen.

“I’m scared if they don’t get him treatment, when he does get out on parole, is he going to get out in a wheelchair?” White said. “These tremors, is it doing something else to swell up his brain or something up in his head? They aren’t doing any further testing to figure out what’s going on.”

White said she was told Logan was being considered for early parole release, but she never heard back from the Department of Corrections.

His lawyer, Gail Johnson, clarified that Logan's application was denied.

Logan told her that medics inside the prison told him that if his tremors got bad enough that he “couldn’t hold a cup” he could be considered for release.

“I feel upset,” White said. “I feel helpless because I can’t do anything to help him.”

Policymakers see a need for reform

State Sen. Pete Lee, a Democrat from Colorado Springs, plans to introduce legislation in a few weeks that will hold the Department of Corrections more accountable for how they handle special needs parole.

The proposal will clarify the definition of “incapacitated” and make clear who is in charge of evaluating public safety risks, medical vulnerabilities and making regular assessments of inmates. Sometimes, Donner points out, inmates, particularly those serving lengthy sentences, may be okay for years, and then suffer a debilitating condition, like a stroke.

Lee said it was disappointing that the Department of Corrections isn't actively considering more infirm inmate releases such as people like 84-year-old Anthony Martinez, who uses a wheelchair, has advanced renal failure and is nearly deaf.

Martinez got out early at the end of last year, not because of the special needs parole program but because Polis granted him clemency.

“We are just trying to get more people being identified as suitable,” Lee said. “I think it’s both a definition problem and the CDOC not doing enough. Clearly, you have to identify them, but in order to identify them, you have to have clarity about who is eligible.”

And, in his effort to overhaul special needs parole, it seems Lee has at least one notable person in his corner: the governor.

When granting Martinez clemency right before Christmas, Polis said: “You have a ... man who is wheelchair-bound and suffering from dementia. While the case highlights the need for reforming the state’s special needs parole process for him, and others like him, at least I am able with my power as governor to be a last recourse to allow him to live his final years with his niece.”

The Department of Corrections, which did not grant an interview for this story, also signaled support, in a statement.

“The Department also agrees with Gov. Polis that statutes around special needs parole need modification in order to provide Corrections and the Parole Board with the tools they need to protect public safety while providing compassionate release for incapacitated inmates,” Skinner said, in an email. “We have already provided input to some legislators who are interested in this issue.”

Last year, Denver attorney David Maxted represented a 77-year-old inmate at the Sterling Correctional Facility serving time for a murder committed in 1989. The man has been in for 31 years and had multiple strokes. He now has partial paralysis and is in a wheelchair.

“There should be some space for redemption in our system, and they should be for cases like this,” Maxted said. “Where someone has served a lengthy prison sentence and they don’t pose a danger to society, our system should be able to consider them anew given the changed circumstances.”

Maxted, whose client’s application was denied in a one-sentence note, called the application process “incredibly frustrating.”

“It is a black box,” he said. “We got a one line response, so it seems like these cases, even though they merit serious consideration, they are not given serious consideration.”

Since the pandemic started, Donner, at the Criminal Justice Reform Coalition, said her office has been inundated by inmates and their families hoping to be considered for special needs parole.

“Not enough attention is being paid to them,” she said. “I don’t think the DOC has embraced that this is their responsibility. It’s so easy to lose people; they fall through many different cracks.”

Corrections spokeswoman Skinner said sometimes prison officials identify an inmate who would qualify for special needs parole, someone with dementia, for example, but they can’t find anywhere for the person to go.

“In some of these situations, releasing the individual may be more harmful to their health,” she said, in an email. “To address that issue, the CDOC has been looking at options for a long-term care facility that would be a public-private partnership.”

Skinner noted these options would also likely be cheaper for taxpayers.

The Department of Corrections has been sued on behalf of several inmates by some private attorneys and the American Civil Liberties Union of Colorado for not doing enough to protect people from COVID-19. The Department entered into a consent decree that, among other things, means they must furnish masks and soap to offenders inside institutions.

Polis was also named personally in the lawsuit and continues to fight the legislation.

That case has been appealed to the state Supreme Court.