Rosalinda Guzman was inside a bathroom stall at school when something begged for attention.

It was on the door, where the school posts announcements.

“That little tiny piece of paper was just so different from everything else that it really caught my eye,” said the 18-year-old student from Kersey who attends Windsor Charter Academy.

“And it said, ‘Are you feeling stressed? Talk to your counselor. Email here or just walk in.’ And so, I did.”

That was in January when the students came back into school to learn in person.

Rosalinda, who goes by Rosi, has long struggled with anxiety, depression and abandonment issues. She also has trust issues from being bullied when she was younger. She said she’s weathered the ups and downs of the pandemic pretty well. But over the past few months, noticed she’d been feeling guilty about eating.

“It really gets in my head that I have to lose weight and I have to be slim and I can't gain weight,” Rosi said. “So that makes me just not want to eat and not be hungry and lose my appetite.”

Eating disorders are up across all age groups during the pandemic. The school counselor encouraged Rosi to start journaling what she eats and how she feels about it. An online eating disorder group helped. Rosi feels she’s eating pretty regularly now. Being back in school helped connect her to mental health support. But while kids are at home learning remotely, many haven’t been able to access mental health interventions that might help.

Students' mental health experiences during the pandemic have been mixed. Some kids are thriving. They like sleeping in a bit more and getting snacks when they want. Others, however, struggle.

Some adults worry about a powder keg of anxiety as more students cycle back into school. Although there’s light at the end of the pandemic tunnel now, some counselors report many children and teens are feeling emotionally, mentally and physically exhausted. It’s unclear right now whether the steps the state and some schools are taking will be enough to meet the need.

“That’s the first wave of what’s happening,” said Dr. Jason Williams, a psychologist and director of operations of the Pediatric Mental Health Institute at Children’s Hospital Colorado. “Kids are reporting more social isolation, more feeling depressed, and disconnected from their peers and their support systems.”

Youth mental health experts anticipate that this is just the beginning of a “tsunami” of mental health needs among children and youth.

Children’s Hospital Colorado is seeing twice as many patients reporting increased anxiety, depression and feelings of isolation and social disconnectedness.

There has been a 10 percent increase in patients coming to the emergency department with concerns for suicide or an actual attempt between 2019 and 2020. (Nationwide there’s been a rise in youth mental health-related visits.) Not only is the hospital seeing more suicide attempts, but it’s also treating kids with more severe mental health issues in its pediatric intensive care unit.

“At one point [in February] suicidal ideation was the number one reason children and youth were coming to the emergency room,” Williams said. “I’ve never seen that actually in my 20 plus years.” Typically, at this time of year, it’s flus, coughs and trauma.

While the number of youth suicide deaths in Colorado was up in 2020, the rates are not statistically higher than the rate for the previous year. Hospital visits, though, indicate some youth appear to be reaching out for help, possibly because schools haven’t been able to provide as many interventions during the pandemic.

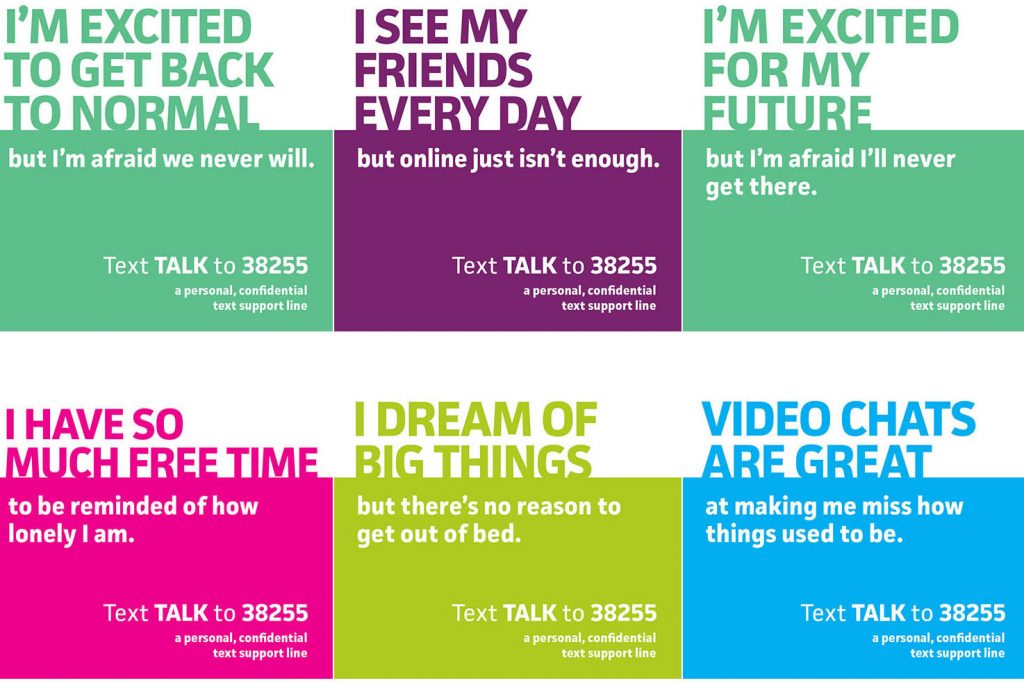

If you need help, dial 988 to reach the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline. You can also reach the Colorado Crisis Services hotline at 1-844-493-8255 or text “TALK” to 38255 to speak with a trained counselor or professional. Counselors are also available at walk-in locations or online to chat.

Children’s Hospital’s inpatient unit has been full since last March. Some young patients wait up to 30 hours for a bed, up from nine hours prior to the pandemic. The same is also true at other hospitals around the state. Seeking help is important because the majority of people who experience suicidal despair do not go on to attempt to kill themselves or die by suicide. Still, as many students head back to school in person, some schools are starting to see Safe2Tell tips relating to suicidal ideation creep back up. One Denver school counselor said students seeking mental health support now report feeling “numb, unsure, sad, lonely, depressed and suicidal.”

Williams said the kids at the hospital talk a lot about not having time with their friends, as well as not being able to look forward to the things kids normally do that give their lives meaning and connect them to others.

“The connection to the world around them has really eroded and almost disappeared in some situations,” he said. “Kids are yearning for this.”

Seventh-grader Kate Hartman said she’s lost a lot of her friends from a lack of contact with them. Hartman has anxiety, sensory processing disorder and ADHD. She likes to be in the middle of the action, helping people. The pandemic put a stop to that.

“I just feel like I didn’t have anything I could control. And I also started to see that I was feeling more sad and just lonely all the time,” she said. She called the year a “rollercoaster.”

Williams said if youth feel they don’t have a sense of their ability to make their way in the world or feel a sense of control, “it becomes very difficult to feel like, ‘I can make a change, that I have a future’… and we are hearing some kids talk about, ‘Well, I don’t know what to look forward to because the future has been so unknown with the last year.’”

Youth is also a time of striving for independence and building autonomy from parents. Instead, youth found themselves stuck in environments they didn’t choose. That’s led to more family conflict, said Williams.

Social interaction is a critical component of a person’s development. For 18-year-old Rosi Guzman, the first months of the pandemic were “shocking and unnerving.”

“I am an extroverted extrovert,” she laughed.

Guzman felt lucky because she was considered an essential worker and could keep her jobs at KFC and as a custodian for a while. That let her be around people a bit more than she would have been otherwise.

Despite the challenges, many young people found a silver lining in the pandemic. It forced both Guzman and Hartman to confront issues and work intensively on coping skills.

The bottom line for students who found a silver lining is you can’t rely solely on the structures within the schools and athletics for socialization.

Hartman became closer to her family; she hung out more with her sister and her Golden Retriever named Emmy. She turns to 80s and Broadway music to help modulate her moods. The family finally got a trampoline, which turned out to be a great way for her to get her energy out. During the pandemic, she believes she’s developing better coping and patience skills.

“Impatience fuels my anxiety and now that I’ve learned those coping strategies, it’s less fearful, and I have a clear path forward and if a rock falls on the path or a tree branch falls, I have the tools to remove that tree branch or that roadblock.”

Guzman meanwhile, started working out more in her room and backyard. She connected with her dog more. The pandemic gave her time to reflect and come to terms with who she is. She realized her boyfriend at the time wasn’t right for her.

“I think I became a little bit more self-aware of what I want and what I need in my life.”

She’s had more time to help connect other youth with mental health challenges to help.

Guzman is excited about the future. Right now, she has six part-time jobs and will graduate high school with an associate’s degree in tow, knocking two years off of college. But the pandemic, as a high school senior, is still hard. Her small homecoming was in a barn. It felt a little sad. As a cheerleader in near-empty gyms, “it felt like we were cheering to nobody.” Her prom may be held outside in tents. There are still mental health challenges.

Dr. Jason Williams of Children’s Hospital believes that the loss of certain social and developmental milestones will have a long-lasting impact on kids’ mental health. But some help could be on the way.

The state hopes to dedicate $8 million in federal stimulus funds toward three free mental health sessions for youth ages 12 and older.

“We want to make it as easy as possible for youth to engage in services, so we’re really looking at telehealth platforms for youth so they can use their phone, their computer,” said Robert Werthwein, director of Colorado’s Office of Behavioral Health.

The state anticipates tapping into a network of mental health providers across Colorado to serve up to 15,000 young people. Werthwein hopes those sessions can connect youth who need it to longer-term services.

Some experts worry there aren’t enough qualified youth mental health providers to meet the demand. Others, like school counselors, recommend that some of the money go to group counseling and alternative therapies or activities.

“The way to adolescents is often through groups, not one-on-one,” said high school social-emotional learning specialist Diana Rarich.

“What if we said, ‘Gosh, you know what? This is the summer of resilience.’ If that's how it was framed, every kid gets access to some activity. You just sign up for it. Some kids may choose a wilderness activity or art therapy,” she said.

Dr. Tiffany Erspamer, a trainer with the nonprofit Partners for Children’s Mental Health said the initial three free sessions will be hugely important.

“But the question I would have is what happens after those three sessions because oftentimes … you may want to continue and what if they don’t have the resources to continue that work? How do we sustainably support children’s mental health in the state of Colorado?”

One Colorado lawmaker may introduce legislation that would provide all public-school students who want it with a mental health evaluation.

The National Association for School Psychologists has recommended that schools engage in universal screening for mental health issues instead of waiting until grades slip. The Cañon City school district is one of only a few Colorado districts that do a universal mental health screening using a 34-question screening survey. Students at high risk are referred to community-based mental health crisis teams.

A fall assessment in school districts across Colorado found that about half of school officials polled cited student mental health as a top priority. But whether schools have the capacity to meet all the needs is unknown.

One study showed that 39,000 students in Denver Public Schools don’t have adequate mental health support, with only 1.5 percent of students enrolled in schools that are fully staffed with mental health professionals. The district has disputed some of the findings, saying the study didn’t account for some staff who provide academic advising and social-emotional support.

Some schools in Denver, unlike in many major districts, conduct a voluntary social-emotional questionnaire at the beginning of the year to identify at-risk kids. In addition, Denver voters approved a mill levy in November that will bring more mental health and nurses to schools this fall.

For schools that need more support, the nonprofit Partners for Children’s Mental Health offers live and on-demand courses to school staff related to mental health and suicide, such as how to train teachers to identify kids at risk.

“I do feel there is a very big lack of teaching the teachers on how to understand mental health issues, especially in communities where it could be seen as a taboo subject,” said Ashley Garcia, a senior at Aurora’s Gateway High School during a recent mental health forum hosted by the education news site Chalkbeat Colorado.

Teacher Crystal Gillis said that her school in the Cherry Creek School District is focused on getting grades up.

“And I’m like, ‘Wait, hold up, we just had about what … three students [die by] suicide over the summer and you all aren’t going to talk about mental health?’”

One national poll found 80 percent of teens wished there was a safe space in school to talk about mental health. Carmen Rodriquez, a sophomore at Paonia High School at the Chalkbeat forum, said that when kids returned to school, no one checked in with them. She doesn’t think teachers have adequate training to help with most mental health issues.

“I definitely wish we had grounding exercises at the beginning of class or guided little breaks through or space or patience for kids who are going through a lot, to take a break and prioritize their mental health,” she said.

Other young people said they felt well-supported, even online. Twelve-year-old Kate Hartman said kids could request counseling support in virtual breakout rooms during classes. She has done so several times herself. She said she wants to — at least for a few years while she’s young — believe that there is good in the world.

“She [the counselor] helped me get through that and I had to sometimes take walks or go get fresh air after, and she helped me access the things I needed.”

Mental health experts, students, and teachers said it’s important for everyone, including parents, to monitor the mental health of students as they return full-time this spring and in the coming year.

Denver Public Schools teacher Gerardo Muñoz said his principal has made clear from day one, “Social-emotional support is your priority. Everything else takes a back seat to those things.”

But Colorado’s Teacher of the Year said he’s heard stories from colleagues in other schools and districts that don’t have the capacity or mental health hasn’t been made a priority so “you’re on your own.”

“We have young people who are going to be coming back with all kinds of trauma,” he said. “They’re not going to be the same as they were on March 12, 2020.”

Help and Resources

Youth

- If you are in crisis or are looking for mental health services for you or someone you know, call the Colorado Crisis Services hotline. Call 1-844-493-8255 or text “TALK” to 38255 to speak with a trained counselor or professional. Counselors are also available at walk-in locations or online to chat between 4 p.m. and 12 a.m.

- Colorado Crisis Services’ Below the Surface campaign, for real stories from youth videos and what to expect on a hotline call or text.

Schools and Parents

- Nine tips for parents to lower the risks of anxiety and depression and keep kids safe (Pediatric Mental Health Institute, Colorado Children’s Hospital)

- Understanding youth stressors, suicide warning signs, life-saving resources, how to talk to children and youth about suicide. English or Español. (Office of Suicide Prevention)

- To help Colorado schools and staff meet the mental health needs of students, Partners for Children’s Mental Health offers trainings, workshops, and communities of practice.

- The Pediatric Mental Health Institute’s Youth Action Board put together a video stressing that parents, teachers, and other adults should pay close attention to teens during this time.

- How to help teens cope during the pandemic is here.

- If teachers see a youth facing a crisis, they can contact Colorado Crisis Services.

- Children’s Hospital Colorado’s Pediatric Mental Health Institute: 720-777-6200 (to schedule an appointment or refer a patient) or online.