Just beyond the antique stores and bike shops of downtown Grand Junction is a hidden, red-rock world. Towering mesas, sheer cliffs and panoramic views of the valley below are all just a few turns off Interstate 70.

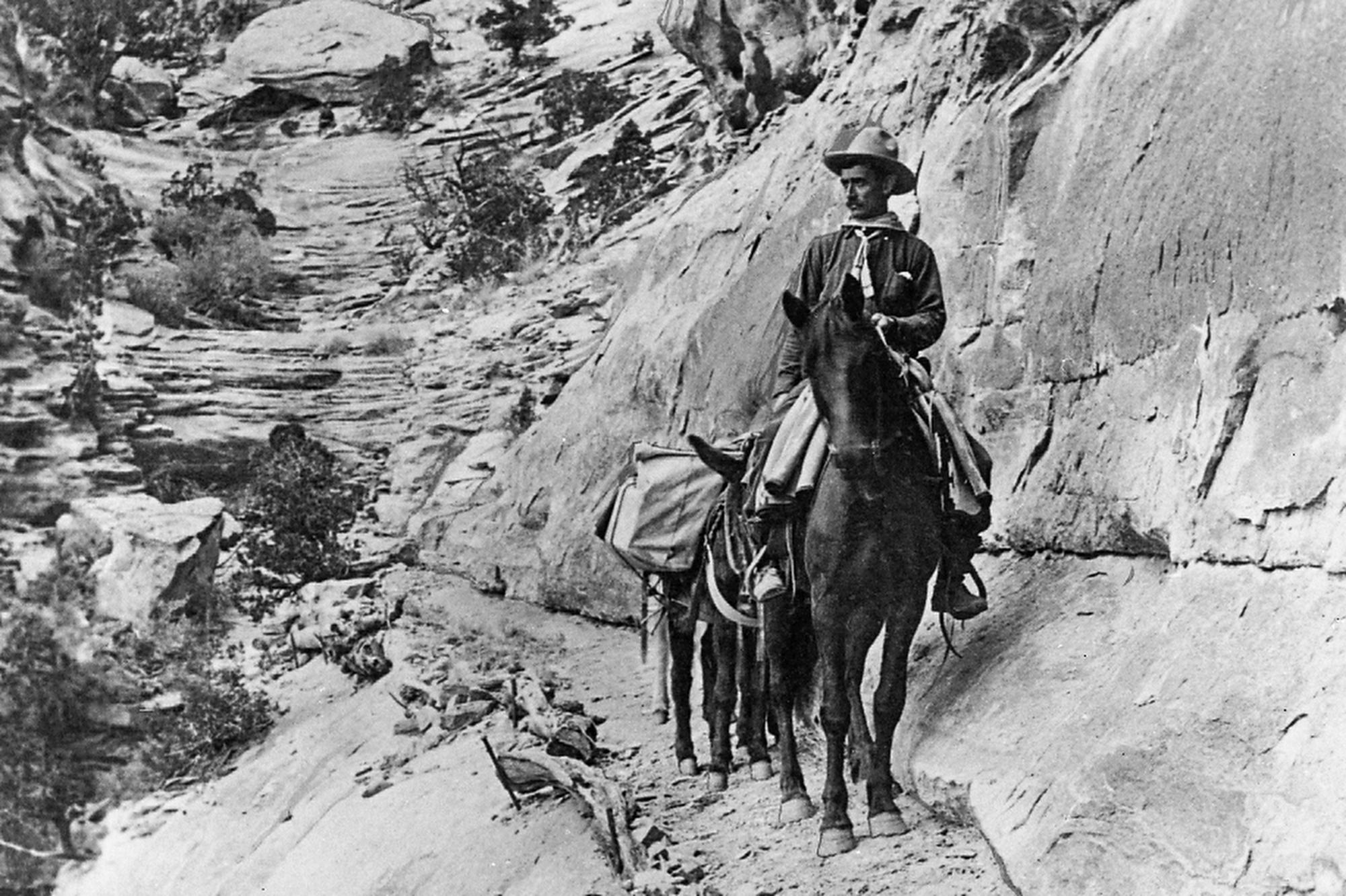

Colorado National Monument was founded 110 years ago, largely because of one man. To some people, he was a visionary and proud patriot. Others saw him as an oddball and hermit.

Arlene Jackson laughed in a way that suggests that she sees some truth in all of it.

“John Otto is … an interesting character,” she said, smiling from Monument Canyon Trail, one of many routes Otto built.

“I think of John Otto as kind of being the foundation or the bedrock,” said Jackson, the Monument’s chief of interpretation. “You don't notice the fact that you're walking on the ground, but yet you can't be here without it.”

She crunched up the rocky trail, a dusty pink ribbon winding past sun-soaked stone walls hundreds of feet high and boulders bigger than pickups.

Grand Junction has changed a lot in the last century-plus. But the Monument has not. That’s Otto’s doing. He first saw this place in the early 1900s, “and he fell in love with the canyons here,” Jackson said.

Otto decided they needed federal protection and recognition. He had already been an activist for mine safety. So he knew how to get attention.

He started writing to the local paper and to local and state politicians — even to the president. He befriended reporters and photographers. He gave tours. He became the future monument’s biggest cheerleader and also a complicated ambassador.

Jackson explained that his “awkward mannerisms” and “ability to truly annoy people” were maybe not as endearing then as they seem now. But some combination of his enthusiasm, relentless lobbying and support from the local paper worked. President Howard Taft signed off on legislation creating Colorado National Monument on May 24, 1911.

Otto was appointed its first caretaker and $1 dollar a month — about $30 in today’s money.

“Even for that time, that’s not a lot,” Jackson joked.

But she believes Otto was happy spending his days building trails and his nights sleeping in a tent.

“He was in his element. He was passionate about the work that he was doing,” she said, “and he was probably pretty tickled with himself.”

He even got married. Through letters, Otto wooed Beatrice Farnham, an artist he’d once met. They found they shared many progressive beliefs, including that women should be able to do more with their lives than just be a wife and mother.

For a wedding gift, Otto gave Farnham a pack mule, Foxy.

“Yeah, that marriage lasted like three weeks,” Jackson said.

Otto’s biggest relationship, it seems, was with the Monument, where he lived for more than two decades. But even that was fraught. He always wanted more: more land for the park, more money for projects, more people to come.

Sometime in the 1920s, Otto became fed up with the federal government, Jackson said, and felt “they’re deliberately putting obstacles in his way.”

So he left. First Otto moved out of his beloved canyons and into town. He later left Colorado entirely, heading to gold country in remote Northern California. He set up a place for himself in an abandoned post office in the small community of Yreka, surrounded by mountains but no red rocks.

“He pretty much disassociated himself with Colorado National Monument,” Jackson said.

As difficult as that sounds, “I have a feeling that that was part of his personality,” she said. “It was all or nothing. And when all became too much for him, then it was nothing.”

Otto died at age 81, too poor for a proper grave. Fifty years later, supporters of the park he helped build bought him a headstone that stands in Yreka. It’s in the shape of Independence Monument, one of Colorado National Monument’s best-known landmarks and its tallest stone pillar. Every Fourth of July, Otto used to climb it, all 450 feet of it, and plant a American flag over the stunning, arid land he loved so fiercely.

A flag still flies there every Independence Day, the tradition carried on by the local search and rescue team. But you can't see it from town. You’ve got to be right there in the park. Otto liked it that way.