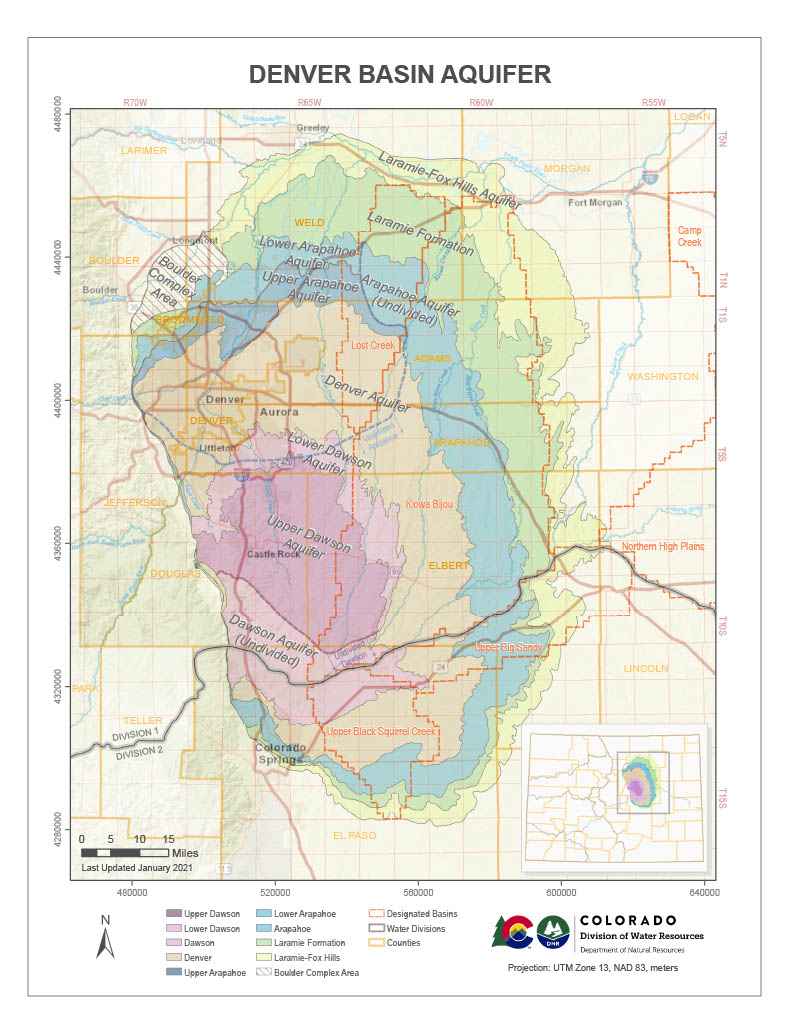

In El Paso County many people drink ancient water drawn from million-dollar wells. Their water comes from the Denver Basin, a geological formation that stretches along the Front Range from Colorado Springs to Greeley and east to Limon.

Although the water is deep underfoot, one of the places you can get a glimpse of the Denver Basin without having to go underground is at the rock outcroppings in Colorado Springs’ Palmer Park.

“Those rock outcroppings are mostly formed from what's called the Dawson Arkose,” said Cherokee Metropolitan District water engineer Kevin Brown. “It's a rough sedimentary rock usually made up of anything from sandstones to larger conglomerate. It looks kind of like concrete. It's the topmost of the four bedrock aquifers that are the Denver Basin.”

The Cherokee Metropolitan District serves nearly 18,000 customers in and around Cimarron Hills on the eastern edge of Colorado Springs. Aquifers are often thought of as giant subterranean lakes, but when you turn on the tap in some areas in El Paso County you may literally be getting water from a stone.

“It's incredible that there is water stored in the tiny, tiny microscopic pore spaces of this rock,” Brown said. “[And if you drill a well], the water is under pressure from the rock and that well is now open space and the water will flow into it.”

This water could be from tens of thousands of years ago, unlike surface water from streams and rivers that comes from rain and snow. According to Brown, that water makes it to the bedrock aquifers of the Denver Basin too, but he said, “it just takes a very, very long time and it happens very slowly, and especially happens slowly compared to how quickly we're withdrawing water, to the point where they are effectively not being recharged.”

A term that's often used is fossil water.

"This water would recharge, but not in a human time timescale,” Brown said.

So Denver Basin water is considered nonrenewable groundwater and the populations using it are growing. Neither Denver Water nor Colorado Springs Utilities rely on the Denver Basin to serve their customers, but some of the big deep commercial wells that serve other Front Range municipal and community water systems are starting to become less productive.

“We had one well that was producing initially around a hundred gallons a minute. We're lucky to get 40 gallons a minute out of it right now,” said Jessie Shaffer, who manages the Woodmoor Water and Sanitation District in the northern part of the county.

“It's really a diminishing return that you get on Denver Basin groundwater these days,” Shaffer said. “Every well you drill, you get less and less yield out of, and it takes more and more wells just to maintain your current level of water supply that you need to have in sufficient level to serve your community, which means more money, more capital improvement projects, and more costs, higher water rates.”

A Denver Basin well can go some 2,000 feet deep and cost millions of dollars. U.S. Geological Survey hydrologist Suzanne Paschke of the Colorado Water Science Center has studied the Denver Basin aquifers. She said models show some areas throughout the entire basin going dry in the next 50 years depending on growth, the amount of pumping and availability of other water resources.

“I don't know if anyone has the shiny bullet that's gonna solve all the problems,” she said. “I think it's a combination of approaches, perhaps looking at ways to use the Denver Basin resource responsibly so that it's not completely depleted.”

Improving water conservation and balancing agricultural, domestic, and commercial uses are important to keeping Denver Basin groundwater sustainable, according to Paschke.

Historically, Denver Basin wells have been the choice for developers despite their expense and uncertainty, according to Kevin Brown with the Cherokee Metropolitan District. That's because there aren’t significant surface water supplies in El Paso County. But, he said, it's not a permanent answer.

“Even if there were no growth, eventually there would have to be a solution outside of the Denver Basin,” Brown said. “You have declining aquifer yields and having to drill more and more wells. And now on top of that, you have an increasing demand from growth and it's squeezing in two directions.”

It's not like people have to worry that water won’t come out of their kitchen faucets anytime soon, according to Shaffer and Brown. But the state expects the Front Range population to expand by more than a third in the coming decades, and the state demographer's office says El Paso County is likely to remain Colorado's most populous county, growing to nearly a million people by 2050.

So Cherokee Metropolitan and Woodmoor Districts are among the region’s water utilities puzzling out how best to accommodate that growth and responsibly use the ancient waters of the Denver Basin.

Read more on what these water managers in El Paso County are proposing.

Editor's Note: This story has been updated to correct the name of the U.S. Geological Survey.