Colorado hasn’t paid what it’s supposed to for special education in at least 16 years. And before that, what it sent to school districts was largely based on what state lawmakers could afford.

A 2006 bill set the amount for students with disabilities — it hasn’t budged then, despite years of inflation. And for students with the most severe disabilities, until just a few years ago, they got 31 percent of what they were supposed to, leaving already strapped school districts to make up the difference.

State Sen. Rachel Zenzinger is trying to set things right for the 12 percent of special education students in the state — and their overloaded teachers and aides.

“I was shocked, I could not believe that we were not fully funding it,” she told a legislative committee recently.

State lawmakers are poised to pass a proposal by the Arvada Democrat and Brighton Republican state Sen. Barbara Kirkmeyer to pump a historic $80 million more into teaching students with disabilities, who range from students with mild autism or a learning disability to students who are blind or who have multiple disabilities.

Starting next year, the extra amount for each student with a disability would rise from $1,250 to $1,750. Students with more significant needs are supposed to get an extra $6,000. The bill would take funding for those students from 56 percent of what they should be getting to 75 percent. It also requires that the funding total increase by inflation annually.

“I know there is a huge price tag on this, but it’s been our obligation and we haven’t met it for 16 years,” said Kirkmeyer during a committee meeting for the bill. “I hope today we can start on the journey to meet our obligation to these kids and their families.”

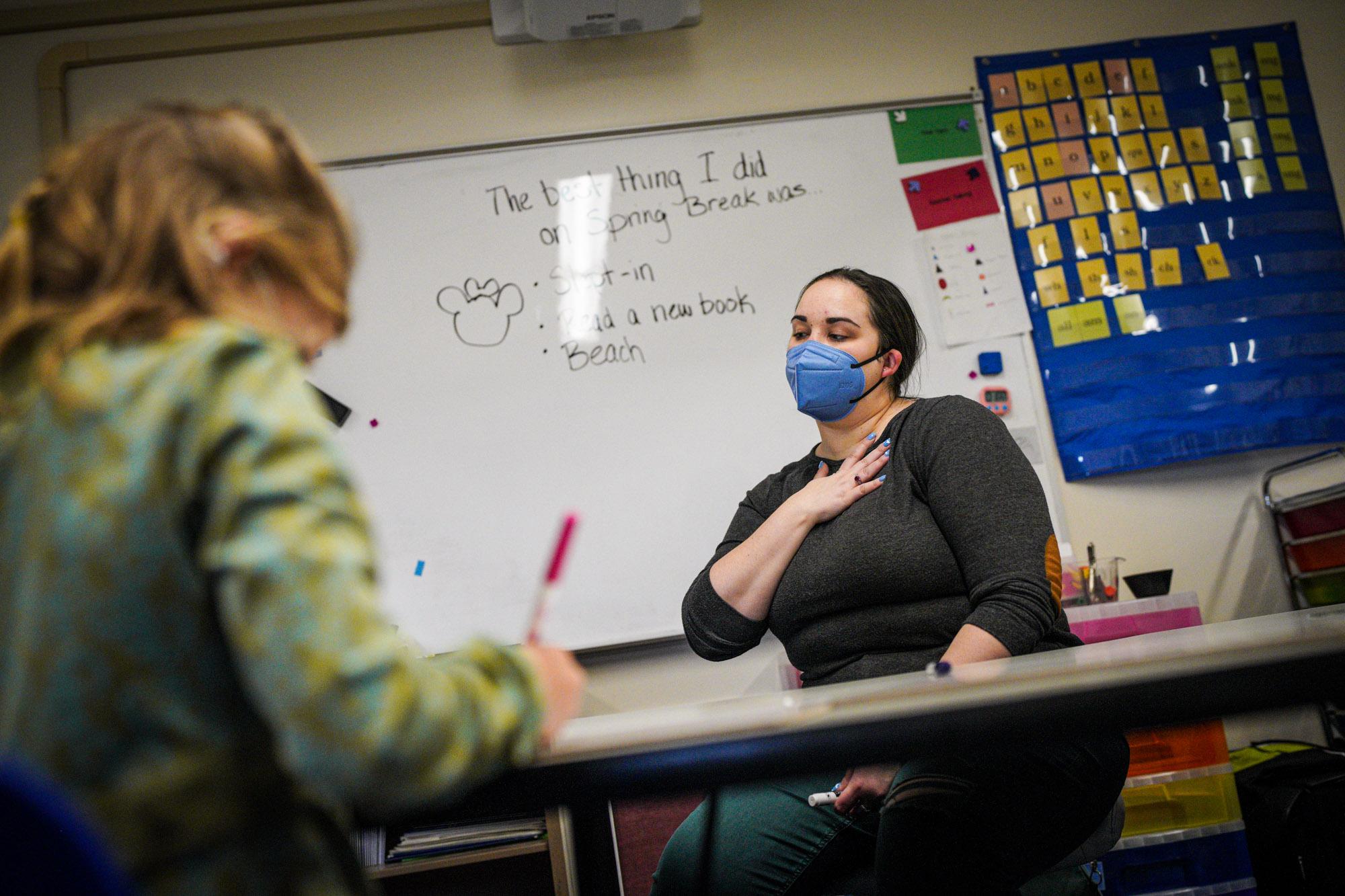

Special education teachers say the demands of the job have left them burnt out

“My current caseload feels overwhelming,” said Jen Holtzmann, who teaches at Lincoln Elementary in Denver.

Under federal law, each of her 20 students has a certain number of minutes of service Holtzmann must provide each week. The steadily rising caseloads, which can go up to 29 for a single educator at some schools, makes it harder to meet students’ needs, she said.

There’s another problem. The severe shortage of paraprofessionals or aides, especially in special education, also impacts students’ instruction. Denver Public Schools places a high priority on including special education students into regular classrooms. For that to happen for students with more severe needs, they need one-to-one support at all times.

There are three students at Holtzmann’s school who need this intensive support. She lost two aides – they’re called paraprofessionals — before spring break. She’s now down to one.

“When I don’t have paraprofessionals, I cannot meet the needs of any of my students,” said Holtzman. “Finding a person who is qualified or capable or has the patience or comes already with the skills is incredibly challenging.”

Paraprofessionals aren’t paid well. Holtzmann says they also need more intensive training from the district. She’d like to train them, but she’s overloaded as it is.

“I have to teach, I have to plan, I have to do IEP meetings, I have to evaluate students, I have to write assessments.”

The list goes on.

Merri Lintz, an occupational therapist, told the DPS school board recently she is currently 40 percent over the recommended caseload for her job description.

“This affects the quality of my services in all areas,” she said.

Other special educators said the lack of resources is fueling the shortage.

“While I’m lucky enough to have a supportive principal, we are not able to give our most vulnerable population the time they deserve,” said Denver special educator Victoria Woods. “Our caseloads are unmanageable and that is why we are seeing such a shortage of special education teachers.”

Passing the buck: How did school districts become 'the payer of last resort'?

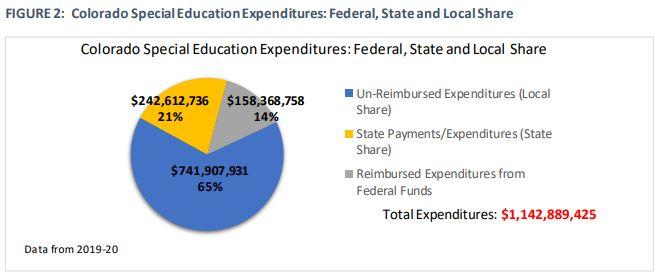

The federal law on students with disabilities went into effect in 1975 with the promise that up to 40 percent of the cost to educate students would come from the federal government. In Colorado, federal dollars have never totaled more than 20 percent of the cost.

So, it fell on states to fund education for children with disabilities, said Lucinda Hundley, who heads up the Colorado Consortium of Directors of Special Education. Colorado created a set of expectations for special education funding in 2006. But every year it’s fallen short. How bad is the gap? The state only funds 23 percent of the costs to educate children with disabilities.

So, Colorado school districts — already funded well below the national average — have been making up the difference.

“School districts across the United States are required to provide the necessary supports for these children, regardless of cost,” Hundley said. The districts make up the rest — more than $740 million unreimbursed from the state.

To make that happen, many districts have had to take from elsewhere — cutting arts or music or sometimes taking half a point off staff raises.

“They’re providing the education (to special education), but it’s coming at the expense of the entire system,” said Sen. Zenzinger.

During testimony at the Capitol for the bump in funding, one school leader recalled how one district having to eliminate a kindergarten teacher position, “to combine kindergarten and first grade so that the small rural school could pay for a full-time special education teacher,” said Tamera Durbin, who leads Colorado Northeast BOCES, which serves as the administrative unit for multiple small rural districts.

The legislation also sets up a committee to study what it actually costs to educate students with disabilities, and an analysis of funding models in other states, some of which fund students at three times the rate of other students. That committee will recommend changes to Colorado’s funding model.

State lawmakers are expected to finalize the long budget bill, which includes the extra funding, next week.

Districts welcome the new money. But special educators statewide are nervous the money will be used to shore up places in school budgets that were cut to fund special education

One report estimates the actual additional cost on average for special education students is about $10,500.

“Were so far behind in funding that even with the adjustment for this year of the $80 million, that will help … but it doesn’t come close to covering the additional costs are that a district has that are providing those services,” said Tracie Rainey, executive director of the Colorado School Finance Project.

Denver Public Schools spends $20 million on students with mild needs, and $35 million on students with higher needs.

“Students with special needs have not been sufficiently funded for many years or really ever,” said Chuck Carpenter, chief financial officer for Denver Public Schools. “This is overdue. This additional funding is going to help DPS serve students with special needs better by providing the funds that we’ve needed for a long time.

The bill doesn’t, however, require how the dollars will be spent. It could be used to add more special education services or offset the money districts have tapped from their regular education budget.

“There is not a statutory requirement to increase special education expenditures with these dollars,” said Bill Sutter, chief financial officer for Boulder Valley School District. “It is a reimbursement for what districts are already doing.”

Boulder Valley School District gets about $7.5 million in state funding for students with disabilities but spends an estimated $53 million. Because there is such a huge gap, Sutter said the district would need a lot more state dollars before it necessarily adds to special education programming. All districts meet the requirements in a student’s special education plan under federal law, however improving services and adding programs beyond required services needs to fit within a district's resources.

“This is money coming in for the things that we’re already spending on … that we haven’t been able to do something else whether it’s wages, or programs.”

There is tremendous pressure on some districts that haven’t been able to keep up with salaries for a whole host of positions — paraeducators, teachers, bus drivers, custodians — because the district has had to put resources into required special education services.

DPS special educator Jen Holtzmann hopes some of that money will boost wages and training desperately needed to hire more paraprofessionals or to help reduce caseloads. It’s hard for her to imagine funding has not really increased since 2006.

“2006! That’s the year I graduated high school,” she said. “I’ve been teaching in this deficit for as long as I’ve known. Would that mean another half-time special education teacher? That would be nice.”

In Denver, educators want a seat at the table for how those funds should be spent.

“What worries me is that it’s possible that building leaders forced to make a tough decision … do I keep music or do I staff special education to the full extent that I know is necessary, or do I staff it at half knowing that my special educator has always made it work because they’ve had to,” said bilingual speech language pathologist Michelle Horwitz. “I don’t think people can do that anymore.”

She said she’s seen many colleagues leave because they know they can have a bigger impact on children if they worked in outside facilities like pediatric clinics. Horwitz also wants special educators at the table because in Denver, where schools set their own budgets, she said she’s noticed an inequity in how special education is funded in each building.

“We want to make sure all schools can provide the same level of support for those students.”

Jon Paul Burden, director of the exceptional service department for Weld RE-4, is hopeful some districts will spend the money on investing in their special education staff to retain them, hiring incentives or increasing paraprofessional salaries. He’d like to invest in training teachers, paraprofessionals and the appropriate support for students with disabilities. He said his district intends to expand special education services like center-based programming.

“Ideally, what I would like to do is to have the capacity to never have to send a kid outside of my district to get what they need,” he said.