The economy was shutting down and rent was due. It was March 2020, and attorney Zach Neumann was scared about what would come next for Colorado’s hundreds of thousands of renters.

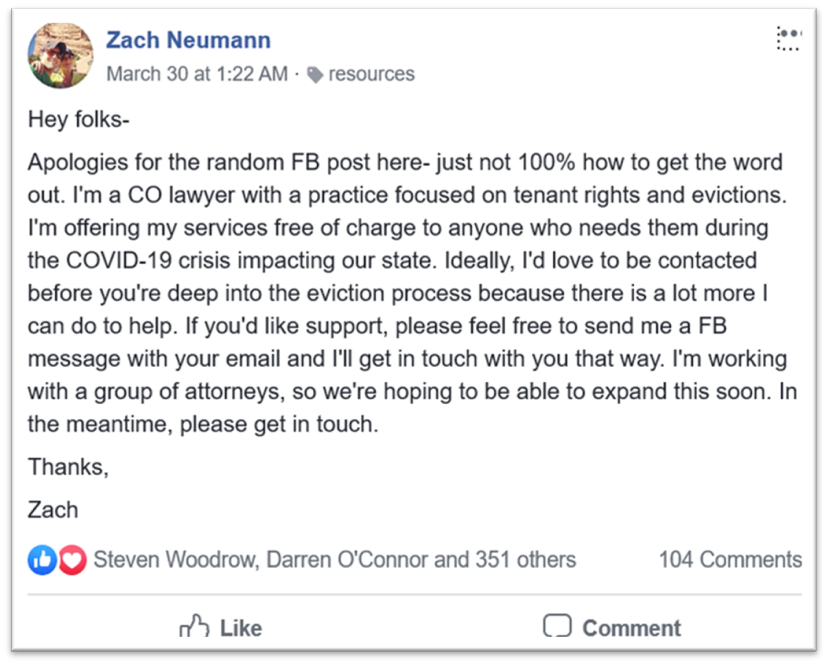

So, he posted on Facebook: “I’m offering my services free of charge to anyone who needs them during the COVID-19 crisis impacting our state.”

When he logged back on the next day, more than 500 messages awaited him.

“It blew me away,” said Neumann, 38, an attorney who represents tenants in eviction cases. In the first weeks of the pandemic, he had been talking with his friend and fellow attorney, Sam Gilman, 30, about how people would pay their rent if they were unable to work.

At the time, the unemployment system was overloaded to the point of failure. Neither the state nor federal government had issued their temporary bans on eviction yet. And many of the resources that would be offered later in the pandemic were not yet available.

Instead, with nowhere else to turn, hundreds of people were flooding Neumann’s inbox with desperate requests for help.

“We said, ‘Man, there's really something here that we have to engage with,’” recalled Neumann.

That Facebook post was the beginning of the COVID-19 Eviction Defense Project. In its early days, the group consisted of Neumann, Gilman and fellow attorneys Javier Mabrey, Carey Degenaro and Burt Nadler providing legal advice and representation, free of charge.

The group also contributed to research that was cited by the Centers for Disease Control in the Sept. 2020 order that banned evictions nationwide for nearly a year.

Over the next two years the Project grew exponentially. Today, the CEDP has about 100 full-time employees, including Gilman and Neumann, with representatives scattered across Colorado.

It is one of the main groups in charge of administering tens of millions of dollars of federal and state rental assistance funds — and its leaders take pride in providing assistance in about 24 hours in many cases.

In all, the group’s 2022 budget was more than $80 million. The vast majority of that — about89 percent — was federal rental assistance the group sent directly to clients. The rest went toward costs directly associated with providing CEDP’s services, such as paying the salaries of tenant advocates, eviction defense attorneys and resource navigators, plus about 2 percent for overhead such as office space, accounting services and executive salaries.

In all, the group estimates it’s served more than 31,000 people, most of them Black, Indigenous or Latino. It’s also lobbied on laws about tenant rights and predatory towing, and one of its early contributors, Mabrey, was recently elected to the Colorado statehouse.

Now, the group is preparing something new: On Wednesday, CEPD renamed itself the Community Economic Defense Project. Under that new name, the group plans to provide not just assistance with rent money and eviction cases, but also to serve as a single location where people can get help with numerous other issues that can knock people’s lives off track, like predatory towing.

“That's really what economic defense is about. It's that single point of entry, meeting a family or an individual where they are,” Gilman said.

The renaming comes at a turning point, not just for the group but for Colorado’s renters.

Early in the pandemic, Neumann and others had warned about an “eviction tsunami” affecting potentially tens of millions of laid-off and furloughed renters. That didn’t happen — thanks, Neumann says now, to the ambitious government response, including the moratoria and tens of billions in rental assistance.

But Neumann and Gilman see new threats for renters. Rent has increased dramatically with inflation at the same time pandemic resources are phasing out. The federal eviction moratorium ended more than a year ago and federal assistance money for renters is running out. The state has stopped accepting new applications for the Emergency Rental Assistance Program and its funds will run out in a few months.

Recently, the number of eviction filings in Colorado has trended more than 10 percent higher for 2022, compared to pre-pandemic levels.

“I think policymakers now really have to reckon with the scale of that problem,” Gilman said. “Unfortunately, it's here to stay until we can build enough housing and keep people in their homes to bring us to that future.”

Other organizations meant to help low-income households have seen similar growth during the pandemic. For example, the Colorado Poverty Law Project has doubled to 19 full-time employees in the last year, said deputy executive director Jack Regenbogen. The nonprofit provides legal defense for tenants, but also has started providing help with other housing issues.

But much of the growth of these groups has been powered by temporary infusions of federal cash. Besides emergency rental assistance, local governments have also used federal grants to pay for eviction defense services.

The leaders of the nonprofits hope that state lawmakers will provide more state money to continue the services.

“What I’m hoping we can communicate to state policy makers is the need to sustain the legal aid infrastructure,” Regenbogen said. “Legal aid coupled with emergency rental assistance makes a huge, profound, difference.”

Housing could be a significant issue when the legislature reconvenes in January.