Van “Kendy” Nguyen, 16, didn’t know anything about computer science.

Gradi Kabeya, 17, hadn’t done any coding before but said computer science seemed cool and useful.

Hazel Ochoa, 16, had dabbled in coding a bit and wanted to know how multi-player games were made.

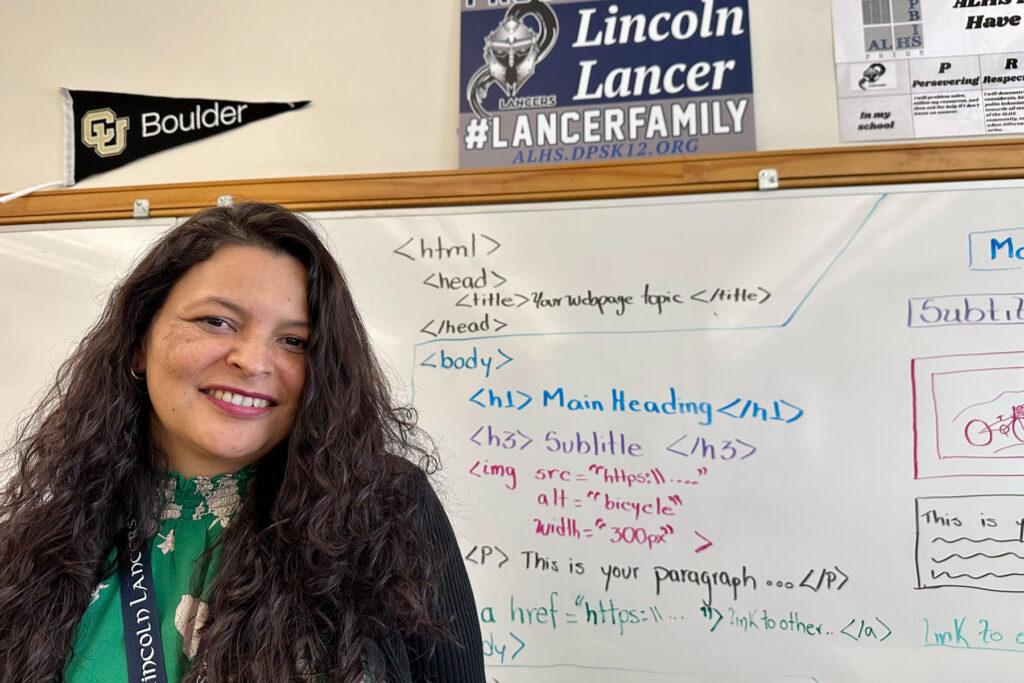

All three found their way into Yolanda Velasco’s Advanced Placement Computer Science Principles class. All three like the course’s focus on creative problem-solving, collaboration, teamwork and real-world applications.

“I’d rather learn something that will help me in life later than just something boring,” adds Nguyen.

As girls, they weren’t alone in the class. Kabeya took the class last year and it was more than half girls. And for that, Abraham Lincoln High School won a national diversity award earlier this spring because girls made up a majority of Lincoln’s AP CSP class.

The southwest Denver school was one of only 14 schools in Colorado to receive the honor, and some of the others were technical or private schools. Just over 800 schools nationwide received that honor out of more than 6,000 offering the course.

Velasco tries to show girls they are capable and have the knowledge to do computer science.

“I try to break that stereotype or stigma about it and let them know that they have the skills to do it, or they can develop the skills if they don’t feel as confident.”

Many people still equate computer science with boys and men

Only one in five computer science degrees in the U.S. go to women. The median annual wage for computer and information technology occupations was $88,240 in 2019. However, women make up just a quarter of people in computing jobs. Some say the culture of the field with an abundance of male-oriented images of computer science excludes women. That didn’t stop Kabeya from enrolling.

“I think instead of discouraging me, it kind of motivated me,” she said.

She discovered computer science has a lot to do with creativity and practice.

“Intelligence has nothing to do with it because it's a skill that you learn and through practice you get better and better at it,” she said. “It's not because this one kid is better at math or good at physics. All the outside factors, it doesn't really have anything to do with this class. As long as you pay attention and you practice, you'll do well.”

She likes that there’s no obvious answer that only the teacher knows. Instead, they both figure out problems as they go.

“It allows you to track your steps,” she said. “It allows you to become very attentive and very observative of everything you do.”

In AP Computer Science Principles, they learn Java Script and how to prototype problems, top-down design, loops, binary systems as well as the larger picture of how computers, networks and how the internet works. For a final project, they have to come up with a problem and create a solution in the form of their own app.

Kabeya created an app for colleges to help them choose students according to certain parameters.

'I'm so smart'

One warm Tuesday afternoon, Velasco plans to introduce her class to the first major standard using a pattern of computer bits, zeros and ones, to represent letters, numbers and punctuation. It’s been around since 1963. But Velasco doesn’t tell her students about ASCII right away. She lets them struggle a bit.

The class starts by guessing the meaning of a set of numbers she gives them. Ochoa and Ngyuen start decoding.

July 4. They get it right away.

“The last one is Oct. 31, that’s Halloween,” Ochoa said.

“Oh yeah! Halloween!” Ngyuen replied.

But the class gets harder. They have to create their own code that represents a phrase. Then, while half the class hides their eyes, the other half looks at a phrase and uses their code to translate and share with a classmate.

It’s stumping some of them.

“It doesn’t make sense because we have different codes, we are talking different languages, sí or no?” Velasco said. “We already have the solution in computer science.”

That solution is the ASCII code, which Velasco presents to them in all its glory on a PowerPoint slide.

There are a lot of “Oh, yeah!” lightbulb moments during class.

“I’m so smart,” said Laura García, sighing.

A champion for girls and computer science

Velasco said she hasn’t marketed the class to girls. But word of mouth, and the school counselors, help. It also helps that she can flip into speaking Spanish if needed.

“Since we are applying some tools and strategies in the class for them to manage the language in an easy way, they feel comfortable coming here,” Velasco said.

In fact, AP CSP was designed to attract students from groups traditionally underrepresented in computer science. Students don’t need any coding experience to take AP computer science courses.

The College Board, which designed the course, suggests strategies to boost enrollment in AP computer science among underrepresented groups. Those include recruiting students in groups so they can support one another, letting prospective students visit a computer science class to show creativity and teamwork on display, and explaining to students how computer science can lead to many career fields — for example, graphic design, medicine, political science, and engineering.

Velasco’s own high school had no computers. And her own struggles in becoming an electronics engineer working in IT in Colombia has made her a champion for girls.

“I was the only woman in technology in my university, you know? So that's something that I want to demonstrate to my girls here that they can do it no matter what.”

Junior Ochoa said having a woman teacher does help.

“Having a teacher with the same gender as you, it helps you connect better with them,” she said. “I think it really helps.”

Nguyen, also a junior, agrees.

“It’s easier to talk to them because you feel like if you can do it, we can do it at the same time.”

At the same time, the class taught her that gender doesn’t have anything to do with competency.

“If you’re smart, then you're going to do good. It doesn't depend on your gender, it doesn't affect you at all.”

What’s in store in the future

But for any student, AP computer science can be hard at times. Super frustrating, especially when there’s a bug in the code.

The three said they sometimes questioned whether they wanted to be there. It’s challenging, “when a problem pops up, what’s causing that, how to solve it, and thinking of a solution for it not to happen in the future,” Ochoa said.

Senior Kabeya has another method when she gets stuck.

“You cry for two minutes,” she laughed. “There's absolutely nothing wrong with crying. It really helped me get through this class!”

Kabeya said she returns refreshed and ready to tackle the problem.

Nguyen said for her app project, it took her 10 days to pick a topic and a month to do the code. But she learned persistence, something all three girls will need for the big futures they have planned.

Ochoa hopes to study computer science in college.

Ngyuen will further her studies in business after getting her associate’s degree in business while in high school.

And Kabeya? Medical school with a strong emphasis in computer science in her undergraduate degree.

All three agree on this. They’d like to see computer science introduced to girls in elementary school.

“So they could determine whether they like it themselves before society tells them, no, ‘This is only for boys,’” Kabeya said.