Adams County juries have found two of the three Aurora Police officers who forcibly stopped Elijah McClain in 2019 not guilty of contributing to his death. But Aurora NAACP president Omar Montgomery said that won’t stop his quest for accountability.

McClain’s story was a focal point for protesters who rallied against police violence and racism in Denver, Aurora, and communities around the world in 2020. The protests led to a state investigation, followed by criminal charges against the officers and paramedics on the scene the night McClain was forcibly detained. Advocates for police reform were hopeful that McClain’s family would get justice for his death.

The jury verdicts have disappointed some Coloradans, including activists and a prominent state lawmaker. Montgomery, too, said he is “shocked” at the acquittals.

But Montgomery said he is also laying out steps that could be taken outside the courtroom to hold Officer Nathan Woodyard accountable for his actions, including in initiating physical contact with McClain. Woodyard admitted under oath that he violated his training in doing so.

Montgomery also sees ways that state legislation and policy reforms to Aurora’s public safety departments could be responsive to systemic failures that contributed to McClain’s death and lack of criminal responsibility for it.

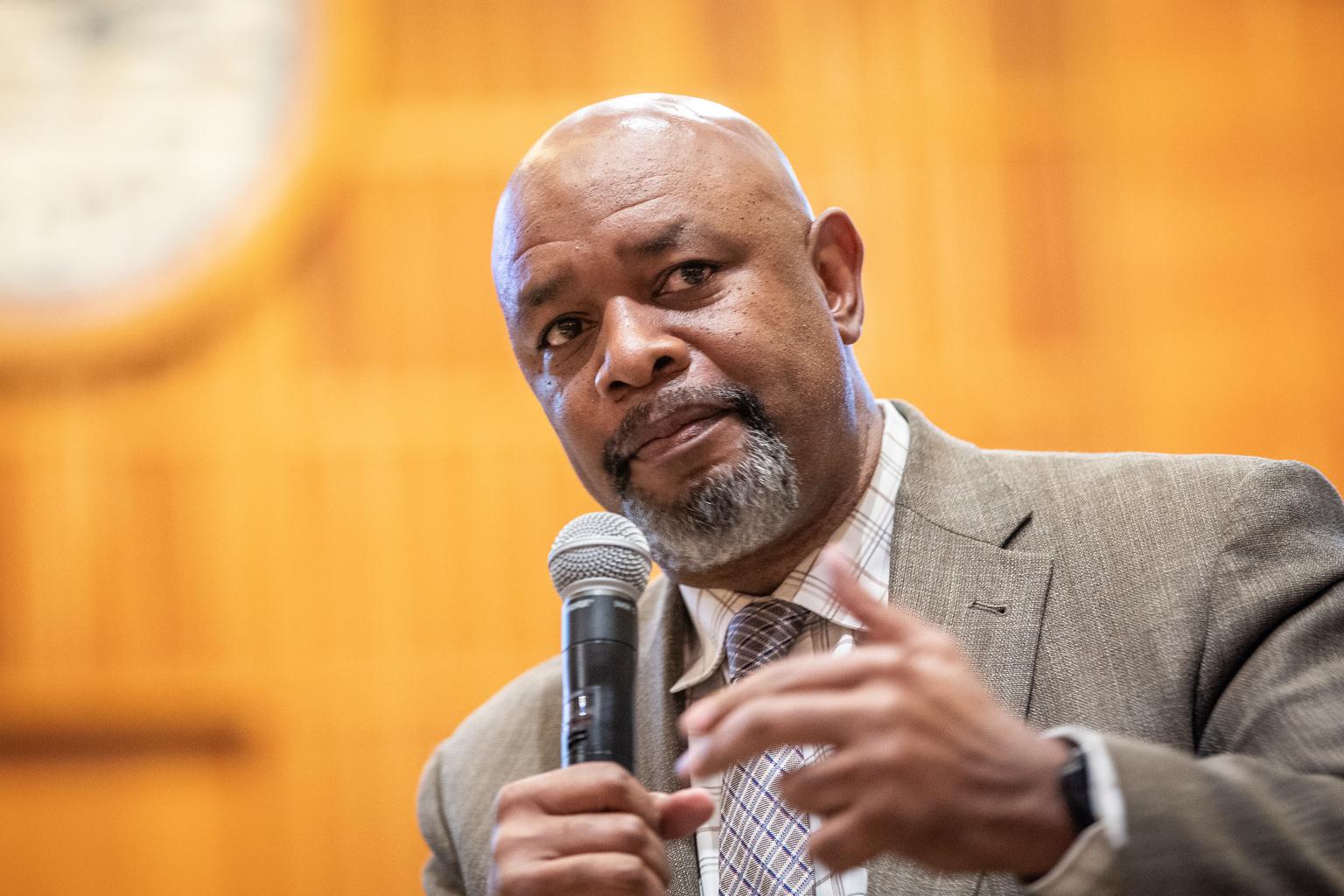

He spoke with Colorado Matters host Chandra Thomas Whitfield.

This interview transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

Chandra Thomas Whitfield: What was your reaction to the jury finding Nathan Woodyard not guilty of manslaughter and negligent homicide?

Omar Montgomery: Shocked, disappointed. The Aurora branch of the NAACP stands with Sheneen McClain [Elijah’s mother] in her disappointment in this verdict. Woodyard’s actions started the chain of events… He should have been held accountable.

Thomas Whitfield: Woodyard said under oath that he violated training protocols, including in his decision to put his hands on McClain when McClain didn’t show any signs of avoiding the officers. So in your view, are the mechanisms for accountability enough, or is there some other way that the entire system could be held accountable for his death and others like it?

Montgomery: Yes, I really think there are further actions that can be taken against Woodyard: First, revoking his POST certification [, or the accreditation that allows someone to be a peace officer in Colorado]. Second, making sure he is not reinstated at any police department nationwide.

There should be some type of communication, whether if a person is found guilty or not guilty, that their actions, their demeanor, and who they are in their core is not the best representation for public safety anywhere. And for me, Officer Woodward lands in that category. As soon as he got out of the car, the first thing he did was dehumanize Elijah MClain. He didn't listen to him, he didn't talk to him, he didn't try to engage him. He just automatically put hands on him. Then he cried later that McClain had tried to grab his gun. There was no evidence of that.

Thomas Whitfield: After McClain died, you advocated early on for more information about what happened. You’ve been in touch with his family throughout this process. Do you feel that the fact that these officers have stood trial offers some degree of justice for Elijah McClain?

Montgomery: First, I want to thank Colorado Attorney General Phil Weiser and his legal team for taking up the case. That was a very courageous act. And it allowed Sheneen McClain and the world to see the evidence and what took place that resulted in the murder of Elijah McClain. That’s just as important whether it's a guilty verdict or a not guilty verdict, because this can help change the way we look at public safety.

This can also help us figure out what future legislation needs to be in place so that, for one, we can protect the good officers who do the work well, and two, get rid of officers who shouldn't be anywhere near any aspect of public safety as quickly as possible. That’s what this case will do, I believe.

Thomas Whitfield: State Representative Leslie Herod told CPR News there are limitations to what laws can accomplish. She said, “There is no law that will make people respect the humanity of other people… What got Elijah McClain into this situation in the first place is blatant bias and racism, ingrained in society. That got him stopped for simply walking to the store.” What is your reaction to her words?

Montgomery: I do agree with her, but there are things that police departments can do internally in their patterns and practices. They can look at a situation and review it with the camera footage, what witnesses say, and decide: ‘This is an officer who doesn't have the demeanor to be on the force and is a danger to the public.’

We need to put steps in place to make it easier for police departments to get those people out. The police union needs to be in line with that, civil service commissions need to be in line with that, city managers, mayors, and elected officials need to make sure that they give police departments and public safety operations the information and the policies they need to get rid of officers if they violate patterns and practices or their training.

Thomas Whitfield: Aurora is under state oversight to change its police and paramedic practices, under something called a consent decree. It’s the first time the state has done this. You’re part of the community advisory council for the reforms. How can the community help make sure police officers choose to de-escalate situations, instead of acting as Woodyard did?

Montgomery: First, the consent decree monitor and the community advisory council hold public forums quarterly. We need the public to come out, to let us know what they're seeing and what they're hearing. There’s a website, auroramonitor.org, where you can report good things that are happening and bad things that are happening. We need to know both, because if there's good behavior out there, we can show officers that they can continue to model it, and that’s great. The bad encounters that take place — let's reveal them, so we can see if we need to do additional training, or if there’s evidence that a person shouldn't be on the force.

The other thing that we can do is continue to vote for people who support having an independent monitor in the city of Aurora immediately, who won’t privatize the public defender’s office, and who are willing to hold public safety officials accountable.

Thomas Whitfield: Another required reform for public safety agencies in Aurora is new training on detecting and preventing bias. You recently told Aurora’s leaders in a public meeting, “If we are afraid to talk about race, we’re going to continue to see some of the same problems we see in our public safety systems… We have to have those tough and courageous conversations if we’re going to improve anything.” Why did you feel it was necessary to speak up on that?

Montgomery: This was during a back-and-forth in a quarterly update on the consent decree. There was a conversation about who should do the training, what the training should look like, and a statement was made that sometimes when officers walk into these trainings, they feel like they’re being called racist, and that they don’t want to engage. This was reported by officials at the meeting. I don’t know if it’s true for all officers.

But for me, if you begin to look at just about every single civil unrest in the modern era of the United States, it had to deal with policing — the Rodney King case, the Watts Riots, the situation in Ferguson, or in Cincinnati, for example. Most of it had to deal with an officer, who was usually white, and a Black citizen, many times unarmed, resulting in their death. If we cannot see that there are racial components in each of those situations, and that race is a key component to solving some of these answers, we must have those courageous conversations.

Go back to the Kerner Report and the Christopher Commission — they point out that if we don’t have a conversation about race in our community when it comes to public safety, we’ll continue to see these things take place. And guess what? Their prediction was correct.