Colorado’s Dearfield, where about 300 Black people homesteaded beginning in 1910, could become recognized as a national park. There’s a study going on now to help Congress decide if it should happen, and statewide, there’s a lot of support for the idea.

More than a century ago, Dearfield was a thriving community of people using the Homestead Act of 1862, which allowed people to own land after farming it successfully for five years. A Black man named O.T. Jackson wanted to try it, and others came along – including Anna and Frank McPherson, who purchased land there around 1906.

Their great-great-granddaughter, Terri Gentry, now lives in Denver and is in her 60’s. She’s one of many people around the state who support the park service designation.

"I am hopeful that with that designation, we can continue to share and celebrate the history of our ancestors and the work and the time they invested in changing their lives,” she said.

Others in support of its preservation include historians like George Junne, professor of Africana Studies at the University of Northern Colorado in Greeley. His area of expertise is Dearfield.

“Oh, we hope that that goes through. Dearfield is important... It was a great example of what Black people could do if given the chance.” He said there was a gas station, a church, a cafe and so much farming that residents sold their crops to neighbors. The area began to deteriorate with the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression in the 30’s. Now, the tiny plot is just about one square mile, with some structures still standing.

For it to become part of the park service, there are four criteria, according to Becky Rinas, a planner with the National Park Service. They are feasibility, suitability, need for protection, and national significance.

“The team is identifying the extent to which Dearfield could, if it were added to the National Park system, fill a gap in public understanding and appreciation of the history of African Americans and the American West,” she said.

The process began in December 2022 with Congress requesting that the National Park Service conduct a Special Resource Study, The study began in 2023 by evaluating the first criterion, national significance.

“We’re looking at the same criteria that we would use to evaluate a national historical landmark,” Rinas said. “We’re looking at its importance in a national context.” To make that determination, she said, “we’re going to be consulting with a lot of subject matter experts and scholars in African American history [and] African American homesteading.”

In January, her office held meetings at the City of Greeley Museum, attended by about 30 people, and Blair-Caldwell African American Research Library in Denver, attended by a dozen more. They’re also asking the public to weigh in using an online form until Feb. 24. The form asks how respondents want the site to be managed, what activities they’d like to see, what about Dearfield they consider unique, and why they support or oppose the designation.

The two in-person meetings indicated excitement around the idea, Rinas said.

“We had a lot of people that said they were super-enthusiastic about the prospect of it becoming a national park service unit.”

The second criterion is suitability, whether such a site is represented within the park system.

“The team is identifying the extent to which Dearfield could, if it were added to the National Park system, fill a gap in public understanding and appreciation of the history of African Americans and the American West.”

The third is feasibility: is it large enough, with enough protection-worthy components and popularity, to be managed at a reasonable cost?

The fourth factor is whether or not it actually needs to be protected. If some other entities were managing it successfully, “we would be hard-pressed to say that National Park Service Management would be superior because that [other] entity might already be doing a great job.”

Local proponents argue there’s ample reason to warrant Dearfield becoming a unit of the NPS, including archeologist Bob Brunswig. He began doing archaeological research at Dearfield in 2011 with students before his retirement, and with community members after. A dig slated for summer, 2024 will be his seventh.

If NPS took over as administrator of Dearfield, Brunswig’s vision would be to turn O.T. Jackson’s house into a history museum, with the interior being restored to look like it did circa 1920, and prospective visitors will include school children on field trips, tourists traveling through Colorado, and people interested in researching the history of Black homesteading communities of the west – including ones in New Mexico and Oklahoma.

Brunswig said his digs occur about a foot below the surface, around buildings that were once central structures at Dearfield, “because that’s where a lot of the cultural activity would’ve taken place. Two of the standing buildings have fragments of wallpaper in them … we find broken porcelain and China, we find buttons for shirts and for overalls.”

He said Dearfield “exemplifies an attempt to create self-sufficiency and security for an African-American community where opportunities were, at the very least, slim.”

About 90 percent of the land is owned by the Black American West Museum and Heritage Center in Denver, which is run by a board of volunteers. One of them is Daphne Rice-Allen, who said that over the past 20 years, the all-volunteer museum purchased land plots at Dearfield, now owning about 90 percent. The museum doesn’t have the funds to staff it, but would still want to be involved with the park service in decision-making, although it’s too early to speculate on what that could look like.

“I know everybody’s like ‘Oooh, ooh …’” she said of enthusiasm surrounding the potential designation, cautioning: “As exciting as this may sound, it’s important to know this is still way down the road.”

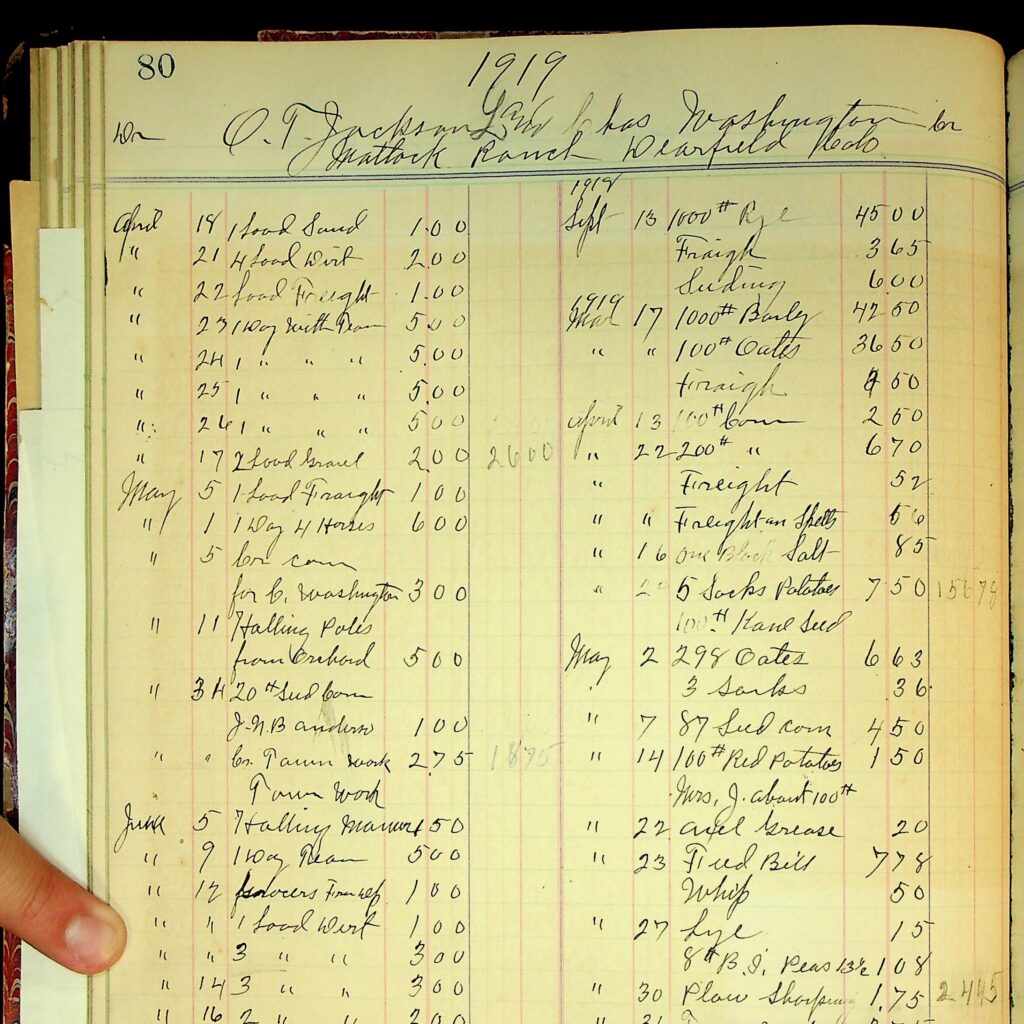

Recently, someone donated business ledgers from Dearfield to a different museum: the City of Greeley Museum, where the manager, Chris Bowles, is another supporter of the prospect of park service protection.

The ledgers show when homesteaders borrowed five dollars for homestead fees, and when founder O.T. Jackson ordered gallons of strawberry ice cream for a fair. Bowles, who received the donation, said it came from someone who didn’t know how valuable the ledgers were.

Donated business ledgers from Dearfield.

Donated business ledgers from Dearfield.

“We had a gentleman [who] had a bunch of books and ledgers, and he said, ‘I think they’re important; I’m not entirely sure – they’ve been in my attic for years.’”

He considers the preservation of Dearfield as a way to honor its legacy: “It’s recognition of that context in which a community like this could be created, and, for a time, thrive.”

The study will be complete in 2025. From there, Park Service will give its recommendations to Congress, which will decide whether Dearfield becomes a site of the National Park Service.

- Dearfield Was A Home On The Colorado Plains For African Americans. A New Film Tells Their Story

- Dearfield Was A Booming Black Community A Century Ago. Now There’s A Renewed Push To Preserve The Ghost Town That Remains

- Could the once-thriving town of Dearfield become a national park?

- Colorado’s Black history — and future — go on display in a new unlikely center of Black culture: Boulder