Tucked away in deep canyons or sometimes hidden in plain sight along a hiking trail is imagery made by the Indigenous peoples who have long inhabited southeastern Colorado. These petroglyphs and pictographs carved and painted on rock cliffs provide a glimpse into the past of a place and of a people.

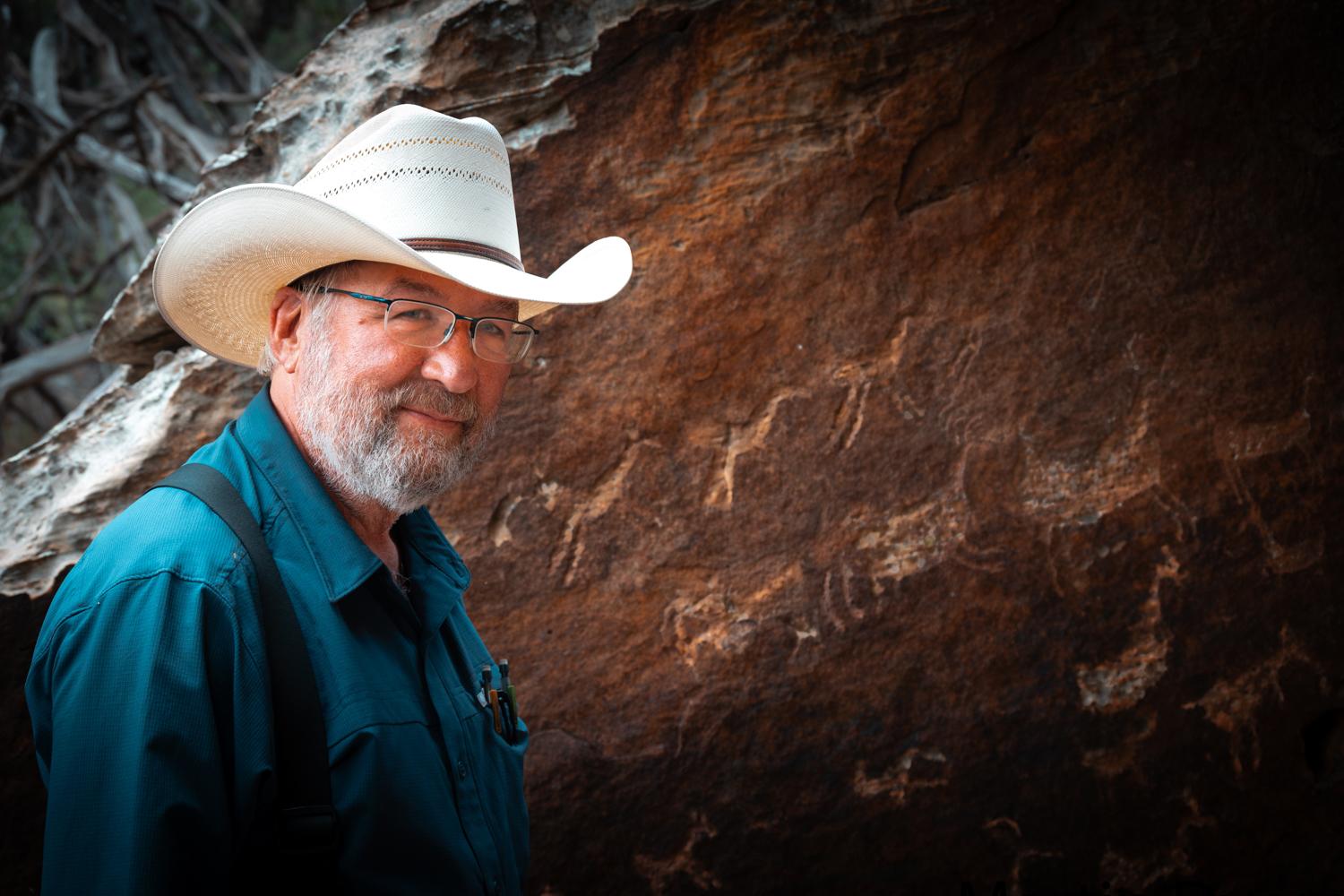

KRCC’s Shanna Lewis spoke with archeologist Mark Mitchell of Paleocultural Research Group about how to see petroglyphs in the San Luis Valley and in southeastern Colorado and why they aren’t found everywhere.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Shanna Lewis: A listener from Crestone asked about petroglyphs along the Rio Grande River around Antonito and wondered if the site has been examined or classified. What can you tell us about this?

Mark Mitchell: Yes, they have been studied and recorded. It's quite extensive. We believe that most of the imagery there relates to the Pueblo Indian use of the Rio Grande Basin and San Luis Valley. We know that there're a lot of sacred places in the San Luis Valley, and undoubtedly, Pueblo peoples made pilgrimages to the valley to visit those places and probably for lots of other reasons, including gathering resources that are available along the Rio Grande in the valley.

There's lots of other rock art sites also reflecting Pueblo use. Overall, there's probably been 60 or 70 rock art sites recorded in the San Luis Valley, of which the one by Antonito is one of the larger and more well-known. Some are small, some of them are quite extensive. There are many more sites than have been recorded. People who live in the San Luis Valley probably know about a lot of them that archaeologists have not yet visited.

Rock art is very widely distributed across North America. There's a lot in the San Luis Valley. It's not everywhere, but most regions have some. It clearly was an important means of expression for Indigenous people in the past.

Lewis: How might one see that particular site?

Mitchell: That site is on public land, but not interpreted (researched and presented to visitors to explain their significance, meaning, and story). The Bureau of Land Management has identified certain rock art sites that are interpreted, and they're ones that they would like people to visit and appreciate and understand something about. There is a group of panels that are interpreted on the west side of the valley in Penitente Canyon near La Garita in Saguache County and it's not too far from the one by Antonito. People can go and not only see it, but they can learn about it because there's interpretive panels on site.

Lewis: Speaking of other places to see petroglyphs, we also had a listener from Boulder who asked where you might be able to see rock art in the Denver or the Rocky Mountain National Park area.

Mitchell: There are some rock art sites in the region around Denver, Boulder, Rocky Mountain National Park, and Larimer County. To my understanding, all of them are on private land, so they're not accessible to the general public. But not too far away from the Front Range is the Comanche National Grassland, southeastern Colorado. There are several really interesting pictograph and petroglyph sites that are interpreted at Carrizo Creek at a place–not coincidentally–called Picture Canyon because of the rock art that's visible there. Another site is Vogel Canyon, close to La Junta. Those are places where people can go see rock art. There's trails that go to them and it's really a good experience.

Lewis: Is there rock art in the northern New Mexico area around Raton?

Mitchell: There is. There's a great deal, and it's really an extension of a huge concentration of rock art that occurs in Colorado along the Purgatory River near the Apishipa and then down into the Cimarron River Valley in northern New Mexico. Most of the New Mexico sites are on private land, but there's a very large concentration of rock art southeast of Raton.

Lewis: We have another listener question that came in from the Denver area. This person wonders why there are so many petroglyphs and pictographs in southwestern Colorado, but not so many in the Front Range area.

Mitchell: Archaeologists have puzzled about this. Why are they concentrated in certain areas and not others? And we can look at Colorado and see hot spots, if you will, where there's lots and lots of rock art, other places where there are rocks but no imagery on them. There may be a number of reasons for it. That form of expression, whether artistic or cultural, may have been important for some Native groups in the past and not important for other Native groups.

It is also possible that a lot of the artistic or cultural expression was done on perishable media like bison hides. For example, parfleche boxes, which are made out of rawhide for carrying things. A lot of them in the historic period were very elaborately painted and decorated. Those hides sometimes depicted cultural symbols, stories or historical events from the native past. Those hides are perishable, and anything like that created in deeper time is no longer preserved.

Zebulon Pike, who came into Colorado in 1806, wrote that he saw what he called pictographs, drawings, icons that were put onto peeled trees — the smooth wood of a ponderosa pine where the bark's been pulled off had images. Lewis and Clark also noted the same thing. So some of the artistic expression may have been occurring, but not on rock surfaces.

Add all that together and today we see hotspots and then areas where there don't seem to be as many.

Colorado Wonders

This story is part of our Colorado Wonders series, where we answer your burning questions about Colorado. Curious about something? Go to our Colorado Wonders page to ask your question or view other questions we've answered.