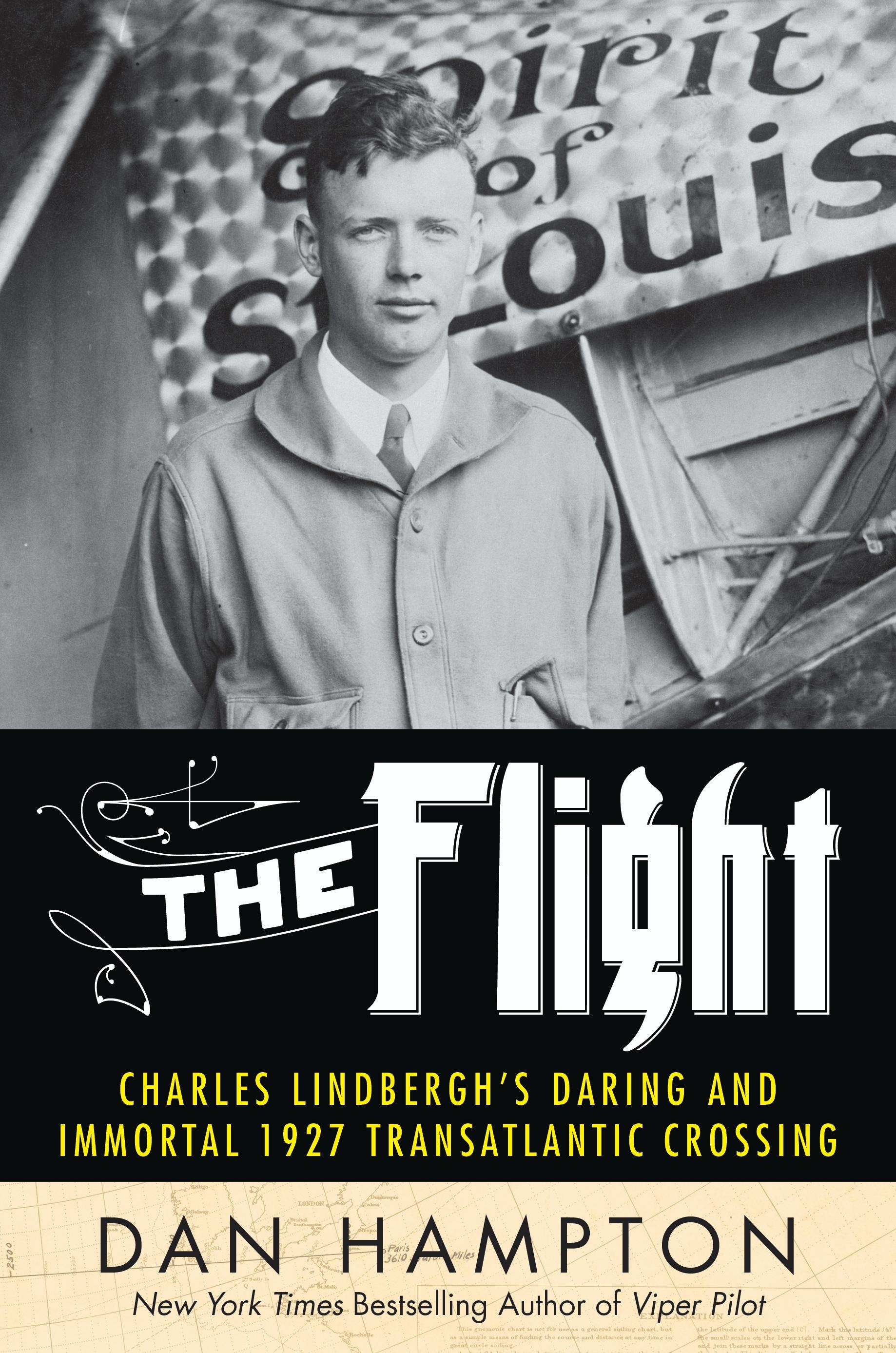

In his new book "The Flight," Colorado Springs author Dan Hampton paints a picture of Charles Lindbergh's 1927 flight across the Atlantic that is both daring and romantic. He describes the threat of ice storms and exhaustion on the 33- hour journey, but also the thrill of skimming just 10 feet above the ocean waves.

Hampton, a retired fighter pilot who flew 151 combat missions during his decorated career, chose to take a pilot's perspective by writing about the historic flight from inside the cockpit, sidestepping later concerns about Lindbergh's Nazi sympathies. He spoke with Colorado Matters host Andrea Dukakis.

The 90th anniversary of Lindbergh's historic crossing from New York to Paris is May 20, 2017.

Read an excerpt:

Prologue Le Bourget Field, Paris May 8, 1927, 5:18 a.m. THOUSANDS OF CHINS tilted back as the large, pale biplane lumbered heavily into the damp morning air above the French capital. Clearing the air field, it began a smooth, climbing left turn away from the clouds darkening the eastern horizon. Called L’Oiseau Blanc, or the “White Bird,” the Levasseur PL-8 had been built for a single purpose—to be the first powered aircraft to y more than 3,600 miles nonstop across the Atlantic Ocean. Thunder rumbled in the distance, and the plane continued turning northwest, its chalk-colored wings very plain against the gray clouds. Brighter was a brief splash of yellow from the cockpit as L’Oiseau Blanc rolled up steeply over the little village of Gonesse. Even though they were expecting it, the crowd gasped when the undercarriage suddenly detached, tumbling through the air into the wet fields below. Jettisoning the 270-pound landing gear was a well-publicized part of the plan as this reduced weight and drag and saved precious fuel. Besides, wheels weren’t necessary to land on water and that was precisely what the two Frenchmen intended to do: set the White Bird down in New York Harbor beneath the Statue of Liberty and claim the $25,000 Orteig Prize for the first nonstop flight between Paris and New York. It was audacious, yet in 1927 no less was expected from Charles Eugène Jules Marie Nungesser and François Coli, France’s leading aviators. Both men had been French Air Service fighter pilots, with Nungesser finishing the Great War as France’s third-highest-scoring ace. When asked about the dangers of the transatlantic flight, Nungesser calmly replied, “A cœur vaillant rien d’impossible.” To the valiant heart nothing is impossible. Handsome and scarred, Nungesser had a panache and contemptuous disregard for danger that personfied the image of French military manhood. He inspired adoring coverage by the French press, who seemed to love everything about the former race car driver, stunt pilot, and military hero. After the war he had married Consuelo “Connie” Hatmaker, a glamorous American heiress, and starred in The Sky Raider, a Hollywood motion picture. The world, particularly France, adored him and never more than that May morning as he set out to conquer the unconquerable Atlantic Ocean. When the biplane rolled out to level flight, the proud red, white, and blue tricolor could be easily seen on the tail. Less visible was the “Black Heart” painted on the fuselage just aft of the open cockpit. Though the crowd couldn’t see the details they knew Nungesser’s “Coeur Noir” well: a white skull and crossbones surmounted by a coffin and flanked by a pair of lighted candles. It was a personal crest, emblazoned on his silver Nieuport 17 fighter during the war, showing Nungesser’s blatant challenge toward mankind’s greatest mortal fear: death. Heading northwest, the plane disappeared into the chilly dawn, the roar of its Lorraine-Dietrich engine fading as it flew on toward Normandy. Without an enclosed cockpit, both men were hunched down out of the cold air behind a large, four- and-a-half-foot windscreen. Their bright yellow, heavy-weather flying suits were fur lined and electrically heated to stave off freezing winds aloft. Nungesser’s navigator, François Coli, was on the right side, seated a bit behind and slightly lower than the pilot. During the war Coli had lost an eye, thus acquiring the nickname the “One-Eyed Devil,” but he had also once been a sea captain and was intimately familiar with maritime navigation, particularly in the North Atlantic. An accomplished pilot himself, Coli was a superb navigator, and it was he who had worked out the route’s details. Coli’s tools included the very latest technical instruments: a ground speed indicator that corrected the airspeed indicator for wind; a Le Prieur navigraph to give surface alerts over water; and a Coutinho sextant for astral navigation. Gago Coutinho, the Portuguese aviator who’d first own across the South Atlantic in 1922, had modified a maritime sextant with an artificial horizon so it could be used effectively in flight. But the navigator’s main instrument was a large Krauss-Morel com- pass. In L’Oiseau Blanc it was horizontally mounted, similar to a binnacle that Coli would’ve used aboard ship. Placed in front of the stick, both men could see it plainly and follow the plotted course. Day or night, with clear skies, Coli could also check their position trigonometrically using his sextant. With a precise heading, two chronometers for measuring elapsed time, and a ground speed indicator the White Bird’s position would always be known. Charles Nungesser sat in the left seat with the throttle lever and mixture control beside him on the bulkhead. The con- trol stick was long, slim, and topped with a pommel for easy gripping. Facing him was a panel dotted with gauges for monitoring oil temperature, and fuel, and a tachometer showing the engine’s revolutions per minute. Among his ight instruments were a Chauvin & Arnoux bank indicator, a vertical velocity indicator, and a Badin-Aéra flight controller. The White Bird had been completed in early April, and both men had then spent the next twenty-two days accomplishing a series of flight tests in preparation for the crossing. Operating primarily from Villacoublay, southwest of Paris, Nungesser had reached a top speed of 124 miles per hour with a practical ceiling of 19,800 feet. During testing he hadn’t attempted a fully loaded, maximum-weight takeoff, preferring to risk this only once on the actual flight. Supremely con dent in his own abilities and Coli’s skills as a navigator, he was certain it could be done with no issues. The French ace felt they were ready but would state to the press on May 4, 1927, “The least negligence, the least mistake, the least impatience could make everything fail.” CROSSING THE COASTLINE near Étretat, Nungesser and Coli continued over the English Channel, where they were observed and reported by a British submarine.* For the next several hours scores of keen observers spotted the paunchy aircraft as Weymouth, Exeter, and dozens of other southern English towns passed under its wings. When they reached the island’s west coast, the squat white tower of Hartland Point lighthouse would have been clearly visible as the two Frenchmen flew out over the Bristol Channel. With its immense 48-foot wingspan, the 11,102-pound L’Oiseau Blanc was roughly the same width as current-day airliners. It was easy to see. Growling power- fully, the 450-horsepower Lorraine-Dietrich motor could be plainly heard above the crash of waves and the screaming gulls. Without landing gear, the plane could comfortably maintain a 110 mph cruise speed, which Nungesser intended to hold. But there were always winds, and this was one reason the pilots had chosen an east-west Atlantic crossing, rather than the con- verse. Coli had purposely waited for a low-pressure weather system when the usual westerly winds would be reversed, and today, May 8, there was just such an area over their proposed route. This would produce an easterly, quartering tailwind that would push the White Bird across the Atlantic rather than slow it down. Flying east to west also meant two-thirds of their fuel load would be consumed by the time they reached Newfound- land, so the plane would be much lighter and better able to cope with severe weather in the area. When asked why he’d planned such a route, Coli simply shrugged and said, “Because we are French! If we go there to come here it would appear that we were coming to visit our- selves.” Most critical for his navigation, especially after flying several thousand miles at night, was the challenge of “finding the earth,” as Coli called it: determining their exact position. This problem would be simplified by a landfall near Belle Isle, Newfoundland, which was more than 1,000 miles from New York. If any course corrections were necessary, there would be sufficient time to do so, while in contrast, anyone flying to Paris from New York would only have 500 miles after Ireland to make course corrections. A landing in Paris would also be at night, a considerable challenge on a strange field after flying for forty-odd hours. The reciprocal argument was also very true. The Frenchmen only had a 500-mile outbound leg to ensure an exact course before departing the Irish coast. But Coli had picked prominent landmarks across the British Isles to guarantee a solid north- westerly heading. Twelve miles off the Devon coast in the Bristol Channel, Lundy Island was just such an ideal navigation point. Having long been a pirate haven, the reputation of the rugged little speck may have appealed to the pair of renegade Frenchmen. Shortly after 10 a.m. the White Bird crossed St. George’s Channel and struck the Irish coast at Dungarvan. Taking his bearings from the Cunnigar, a long finger of land sticking into the bay, Coli corrected their course, and they passed just south of the town. Sunday mass was under way so many people caught sight of the white aircraft, including J. Dunphy, a retired Royal Navy officer, who clearly saw French markings through his field glasses. For the aviators all was well; deep vales trapped the low mist, but the sky was perfectly blue a few hundred feet up. Waterford, Tipperary, and Limerick counties rolled by, their lyrical Irish names strange to French ears. Countless gray rocks speckled the emerald meadows as Ireland, soft and green in the morning light, concealed the threat that lay ahead. L’Oiseau Blanc was positively spotted over Sugar Loaf mountain, Cappoquin, and Glin as it flew steadily on, always northwest. Just before 11 a.m. it was sighted a bare fifteen miles from the Atlantic coast over Kilrush, near the Shannon River. As the plane passed over Scattery Island both pilots could see the vast blue shimmer of the open ocean. Off Nungesser’s left wing the stark, hard cliffs of Loop Head peninsula jutted forward into the cold Atlantic; enormous waves slammed against the granite rocks, throwing spray hundreds of feet into the air. A white lighthouse perched near land’s end, like the nail on a green nger pointing the way west. At 11 a.m. an eight-year-old boy named H. G. Glynn was climbing Knocknagaroon Hill, near Carrigaholt on the west Irish coast. Hearing a strange sound he looked up, shading his eyes against the glare. The boy watched, transfixed, as a large white biplane serenely crossed the shoreline, chasing the sun to the west out over the Atlantic. It was never seen again. From The Flight: Charles Lindbergh's Daring and Immortal 1927 Transatlantic Crossing by Dan Hampton, on-sale now and available for purchase. Reprinted with permission from William Morrow/HarperCollins |