Approximately 140 soldiers returned to Fort Carson last week after a nine month deployment in Afghanistan, a sign that the U.S. combat mission there is winding down. As more soldiers come home, public health experts at the University of Colorado are paying close attention to a subset of U.S. troops: Native Americans.

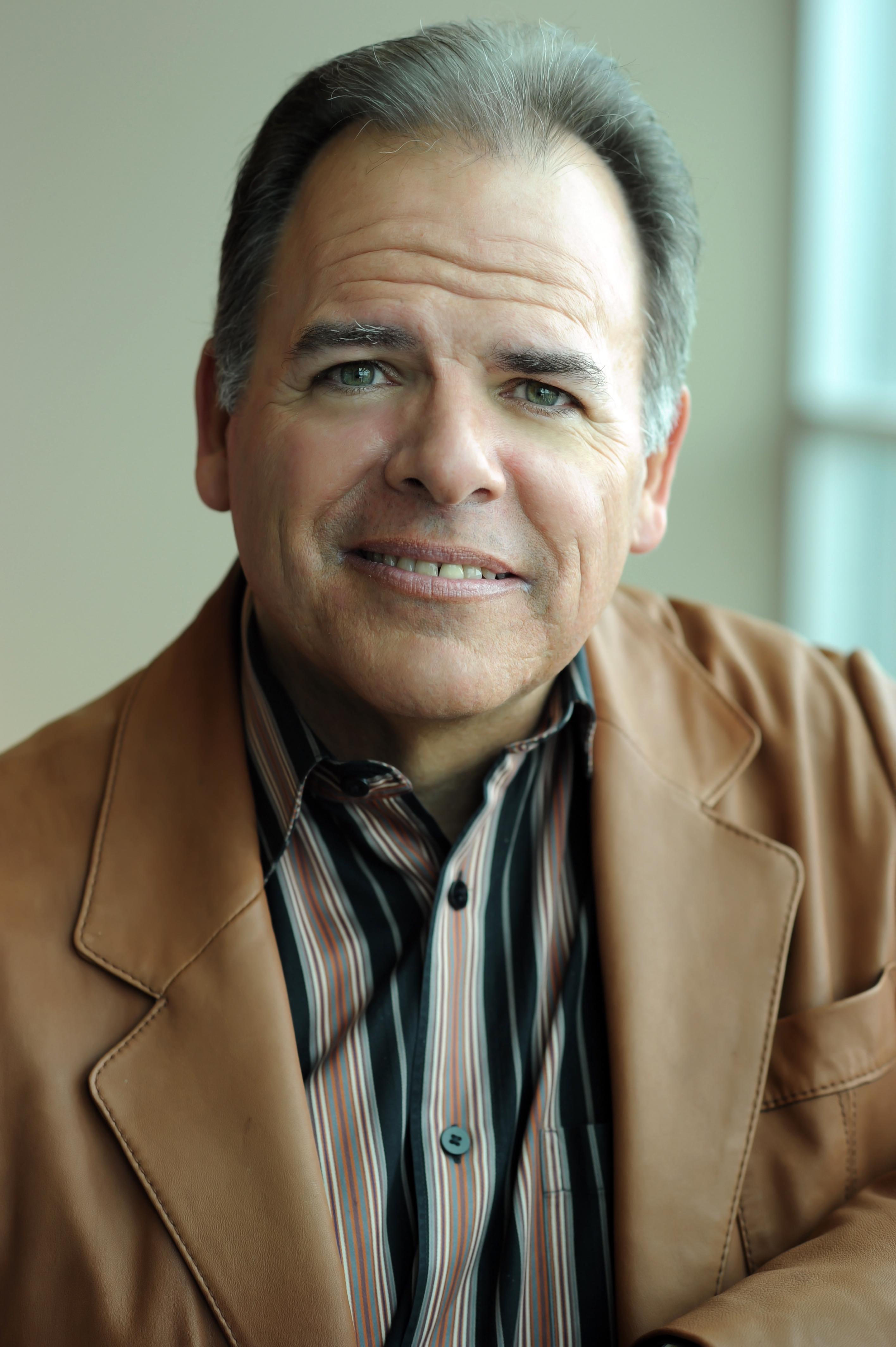

That's because American Indians and Native Alaskans who serve in combat are two to three times more likely than their white peers to suffer mental anxiety including post-traumatic stress disorder, says Spero Manson. He teaches public health and psychiatry and leads the Centers for American Indian and Alaska Native Health at the University of Colorado’s School of Public Health.

Manson says conditions like PTSD are age old. If you read for it, they're even in Homer’s ancient Greek epics, “The Iliad” and “The Odyssey.”

“The returning warriors of that time came back to their local villages and communities exhibiting many of the same symptoms that veterans today, who have seen combat, do,” Manson says. “They’re irritable, quick to fight, they distance themselves from others. They’re very difficult to reintegrate into their communities.”

Soldiers in the World Wars I and II had similar experiences, Manson says, and were often told to "buck up and move on." But overcoming psychological trauma isn’t that simple, he says. It's true not just for troops, but also civilians, he adds, citing the events of Sept. 11, 2001. The attacks have demonstrated on a wide scale the ongoing psychological impacts for survivors, first responders and even those who watched on television, he says.

And the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have brought PTSD to the mainstream.

“Today, with the returning veterans and the risk of post-traumatic stress disorder, and suicide, and traumatic brain injury, I think it’s become part of our everyday discourse,” Manson says.

American Indians and Alaska Natives constitute roughly 1 percent of the current military and veterans, but suffer from PTSD at a disproportionate rate.

Overall, veterans of the Vietnam War suffer rates of PTSD as high as 30 percent, according to the Department of Veterans Affairs. For veterans of the recent Iraq war, it's about 20 percent. For American Indians and Alaska Natives, the rates are much higher according to studies, Manson says.

Manson has a few explanations for why that's the case, and says it has nothing to do with past theories that native peoples somehow lacked the moral character to cope with trauma as effectively as other Americans.

Instead, Manson says, native peoples who serve in the military tend to be exposed to more combat than their non-native peers, adding, “The greatest predictor of trauma among veterans is, in fact, exposure to combat,” Manson says.

Several factors explain why native people are more likely to serve in combat, Manson says, including a persistent stereotype that plays out in the lives of native troops.

“There’s this notion of American Indians as somehow 'at one' with the environment,” Manson says.

He tells the story of a Marine serving in Vietnam whose commander and fellow soldiers volunteered the Marine to lead a patrol simply because he was Navajo. The Marine knew nothing of Vietnam’s jungles, its thick underbrush and rivers. He had come from buttes and open spaces of New Mexico and Arizona.

Another factor that drives native peoples into combat roles is that they are raised to be protectors and to accept such roles when called on, Manson says.

Not only are native people more likely than white peers to suffer from PTSD and other mental traumas; they can also have a harder time dealing with it.

About 40 percent of American Indian and Alaska Native veterans live either in rural areas or on reservations that are far from U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs clinics.

Manson and his staff work to bridge the gap by reaching native veterans through teleconferences. The staff at CU-Denver’s Anschutz campus in Aurora communicates with veterans located hundreds of miles away.

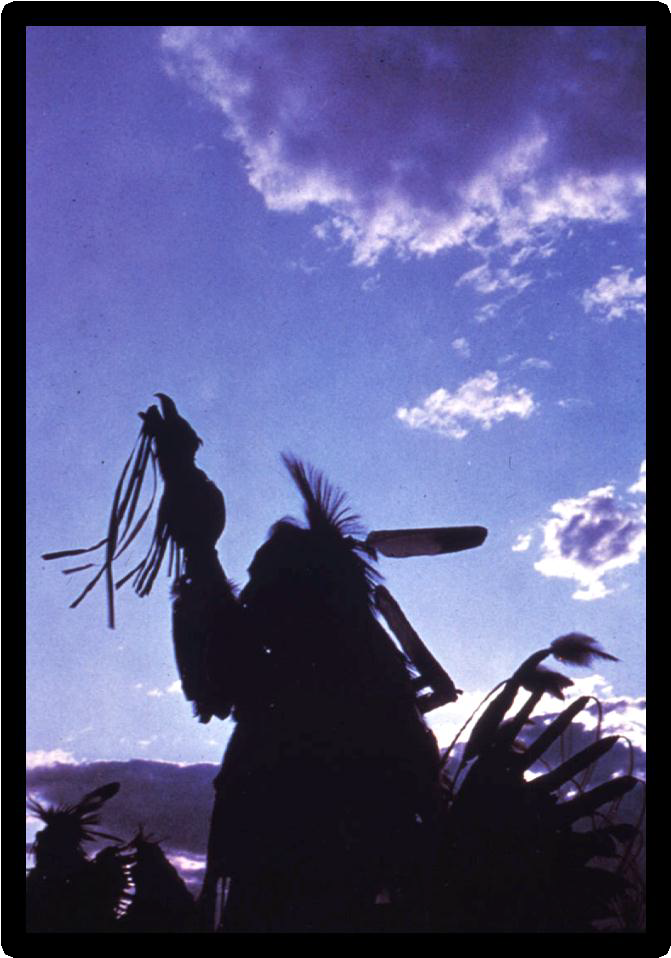

Manson says native cultures can play a powerful role in soldiers' recovery. For instance, tribal ceremonies, such as the Lakota Wiping of Tears, where tears are symbolically brushed from the cheeks, are effective.

Ceremonies conducted before combat, he says, can help lower the likelihood of PTSD. Ceremonies that take place after combat can reduce the duration and severity of PTSD for native troops returning home.

To illustrate what coming home looks like, Manson, who is from the Pembina-Chippewa tribe, tells the story of his son, a Marine, who returned from Iraq in 2004 after a horrible firefight.

“For months later, as we talked and we walked or we sat and we visited, I’d always find him on guard, constantly looking and scanning,” Manson says. “I felt like he wasn’t really paying attention to me. He was paying attention to everything that was going on around him.”

His son suffered from nightmares after losing several comrades in Iraq.

“He something known as 'survivor guilt:' ‘Why me? How could I survive? And, here, my buddies didn’t make it,’” Manson says. “And of course, all soldiers are really fighting not just for country, but for the person who is standing in line next to them.”

His son received help from his community and the VA. He found a job and now helps others recover by sharing how he overcame his challenges, Manson says.

Many people are finding healing, he adds.

“We just have to figure out how to enable them how to do that and to support them in the process,” Manson says.