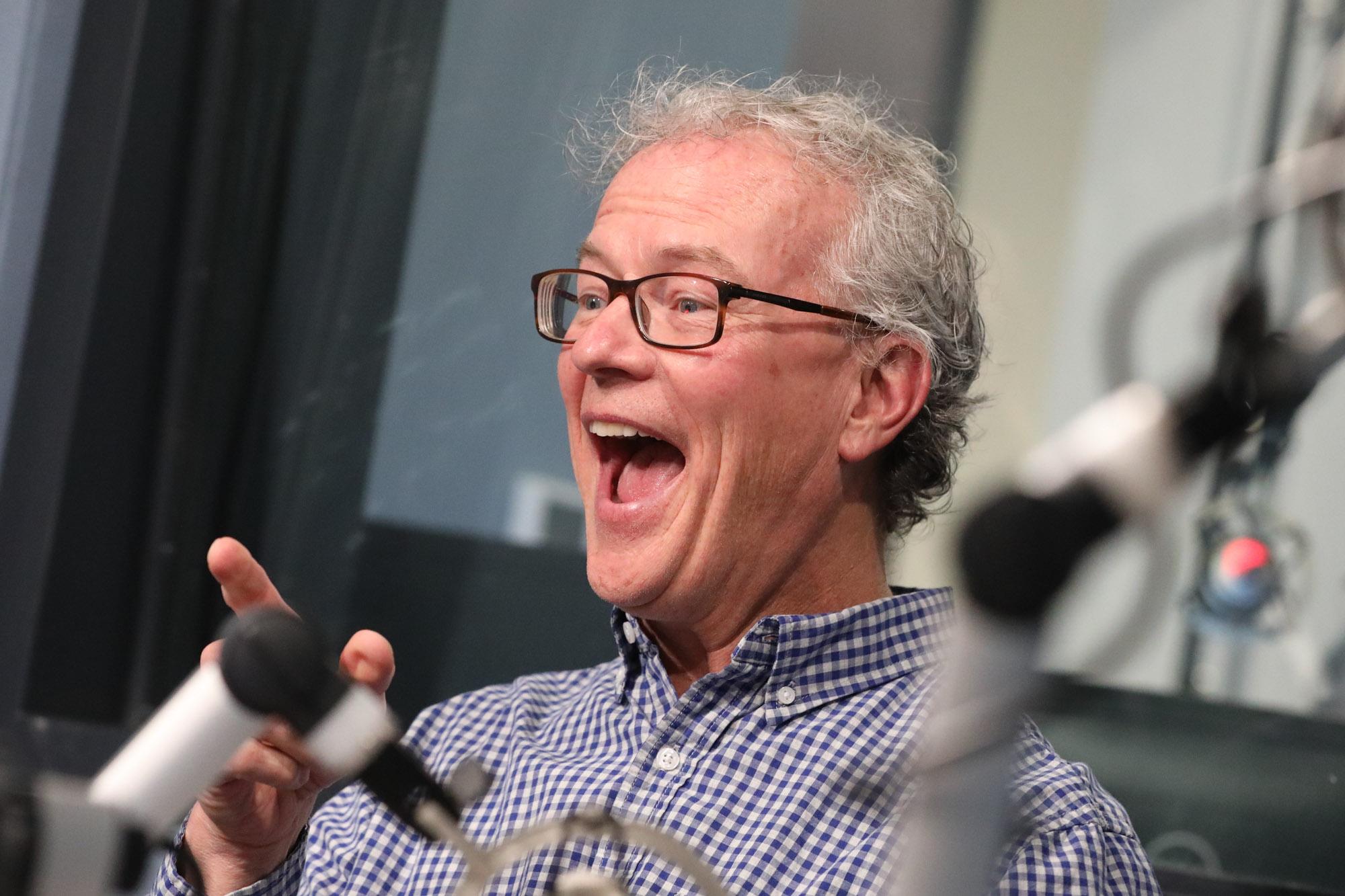

The film CODA gave many moviegoers new insight into the Deaf community. But for Cliff Moers and his family, it was less revelation and more confirmation. Moers and his wife are deaf. All four of their children can hear. That makes the kids CODAs – or, Children of Deaf Adults. Cliff Moers heads the Colorado Commission for the Deaf, Hard of Hearing, and DeafBlind. He and his daughter, Avery, joined Colorado Matters host Ryan Warner, along with Cliff’s ASL interpreter, Christine Pendley.

Interview transcript:

Ryan Warner: Avery, Cliff. Thank you for being with us.

Avery Moers: Thank you for having us.

Cliff Moers: Yes. I really appreciate you having us here.

Warner: Cliff, I'm curious where the film CODA was closest to your own experience.

Cliff Moers: Well, specifically when it comes to the use of language. So when I was watching the CODA movie, the family used English, they're all able to use written English, and just thinking about my own family, how we are bilingual. My wife, Julie and myself, who's Avery’s mother, English is our second language. American Sign Language, ASL, is a visual language. And so that was well demonstrated in that film as well. So our children are bilingual, able to use both ASL and English, but they're also able to use spoken English while my wife, Julie and I, we write English and then use ASL as our spoken language.

Warner: Had you not seen that depicted in a mainstream film before? And what was it like to see that on the big screen?

Cliff Moers: It just showed how people are human. That's how we interact within the world. This is how I've interacted growing up, being fourth generation. I mean, that was really the way that I lived. And so it wasn't necessarily ideal. It wasn't exactly what my experiences were growing up, but it was similar.

Warner: When you say fourth generation, you mean to say going back four generations of deafness in your family?

Cliff Moers: So I'm third-generation deaf. My siblings are deaf. My parents are deaf. My grandparents are deaf. I have nieces and nephews that are deaf. So that means my children's cousins are deaf. And there are some that are hearing as well. So yes, there are four generations of deafness, if you count my nieces and nephews within my family.

Warner: Well, Avery Moers, you are in Boise, Idaho, you're attending Boise State University. You're 23. And we have video monitors set up in the studio today, so that you have visual connection to your father. I guess I have the same question for you – in which ways did CODA most match your own experience? And I suppose, where did it differ for you?

Avery Moers: I think the one area where I related to the most was the collective culture. They really represented how close family is and how close the Deaf community is. I think I related a lot with that. The U.S. and the hearing world are a little bit individual, an individualistic culture. And the Deaf culture is very much collective. It's the group. You support each other, you stand by each other. And I think the movie represented that pretty well.

Warner: It's almost as if there's tension there between the kind of broader American society and that closer-knit society you speak of in the Deaf community.

Avery Moers: Yeah. I think the movie showed that kind of tension. For myself, I don't find it that hard. I'm glad to have both kinds of perspectives. And I'm really glad about my deaf family and my Deaf culture. So there's not that much tension for myself, but I understand why others feel that way.

Warner: I'll just say that you're signing as you speak to us.

Avery Moers: Yeah.

Warner: Obviously so that your father can understand what you're saying, but that is also a choice you've made. In other words, you're not asking his interpreter to interpret on your behalf. Do you want to talk to us about that decision?

Avery Moers: I have never had anyone else speak for myself to my parents. It's just the way I was raised. It's natural for me to include my parents. And it's not something that I think about, like effortly trying to sign in front of them. It's just instinctual.

Warner: Instinctual. What do you consider your first language, Avery?

Avery Moers: My first language was ASL.

Warner: Was ASL. Now Cliff, there is something you have not relied on your children for. Help us understand the role you did not want them to have to play for you and your wife?

Cliff Moers: My wife and I wanted our children to be able to grow up in an environment where they would be able to be children, not in adult roles. And so that's basically why we decided not to use them as interpreters.

Warner: So when you were out in the world, you were at a supermarket or something like that, and you needed to have communication with say a cashier or you were asking where the bread was, who would've been there with you, an interpreter?

Cliff Moers: I communicated using my hands. I would use gestures in order to communicate with the individuals that I needed to interact with, people that I would refer to as non-deaf.

My parents, their generation always had pen and paper with them, ready to communicate at any given time, so they would write back and forth if they needed to interact with somebody. But I don't do that any longer. I do everything on my iPhone. So I open up notes and I type something out in order to communicate with somebody and show them my phone. And that's how I interact with them. I use gestures. It isn't difficult.

Warner: Yeah. In other words, your interpreter in that case is the device.

Cliff Moers: I guess you could say that.

Warner: Avery, how do you feel about that choice your parents made, that they were not going to rely essentially on a little kid to be an interlocutor?

Avery Moers: I am so thankful for their decision. I was able to just enjoy being a child and I didn't need to take on such a responsibility and almost a burden. So I'm really thankful they decided not to use us.

Warner: Are there times though when you were out in – oh, go ahead, Cliff.

Cliff Moers: So what if the police stopped by the house and they were to knock on the door and I answered the door and I were to have one of my kids there? Let's say they're between 9 to 13, do you think that I would want them interpreting for me and the police? That just would not be a right scenario.

Warner: And yet there must have been some circumstances, Avery, when you were out and about, or perhaps someone didn't fully understand the dynamic of your family or they might have gotten frustrated with it, and they just turned to you as the hearing person with expectations that maybe even though you were 7, you were to communicate on your family's behalf. Did you feel that pressure from society?

Avery Moers: Yes. I felt a lot of pressure from the hearing individuals.

Oftentimes my siblings and I would act deaf because the minute they heard us speak or the minute they heard us interact with each other, they're like, ‘oh perfect. We can use them’ It was really hard to explain to hearing people why it wasn't appropriate for me, a child, to interpret for them because many people think – not many people, but I think some people – assume that's me being rude. Like why wouldn't I communicate to my parents?, They don't understand that it’s also rude for them to try and use a child.

Warner: Cliff, I wonder if you have noticed a trend among hearing folks that they try to circumvent you in communication, whether that's trying to use a child as an interpreter or making eye contact with an interpreter, as opposed to you. Is that something that you have felt as a person who is deaf?

Cliff Moers: Yes. All the time. I mean, that's been my experience, always – people not maintaining eye contact with me. When it comes to the language and culture and the values with the Deaf community, it's important to make eye contact when conversing in sign language with each other. And once somebody breaks that eye contact, it's a sign of disrespect.

My children, growing up, often people would turn to them and they would rely on them to interpret for myself and my wife, and I would try to get them out of the picture. That's where I would get a piece of paper or I would get out my phone. And I would try to make sure that I was the one that was communicating with them and trying to help them make that connection with me.

Warner: Avery, I want to key in on something you said just a bit earlier, which is that there were times you would pretend to be deaf. It makes me wonder if you're hearingness and your parents' deafness ever felt like a gap between you or a sense maybe that you lived in two different worlds. I don't want to put words in your mouth.

Avery Moers: I wouldn't necessarily say there is a gap in between me and my parents. I think I'm a lot more similar to my parents than I am hearing people sometimes. But I do think my experience as a CODA is very much in the middle ground. I'm not deaf. I can hear, but at the same time, I am so much a part of the Deaf community and culture and I have a lot of those values inside me, but I live in the hearing world differently and I have access to the hearing world differently than my parents do. But again, I think I'm a lot more similar to the Deaf community and my parents than I'm not.

Warner: Okay. I'm curious if since the movie CODA has come out, have you noticed any difference in how hearing folks treat you? Is the film starting to have some sort of effect on people's awareness, their behavior? And I'll have you start that one, Cliff.

Cliff Moers: I mean, it's basically been a year since that movie's been out. So there's been a lot of conversation about equity and diversity and inclusion. So that seems to be helping to push people to be open-minded. And when they won that Oscar award for that film – they won three different awards – when those were announced, the Department of Human Services, which is where I work here in Colorado, they came to an understanding of what it is, what I do within my work.

I work for the Colorado Commission for the Deaf, Hard of Hearing, and DeafBlind, and often we have these conversations talking about the needs for the communities: How can they have full access? What does it look like to have effective communication? We've been having this conversation for years and this movie comes out and all of a sudden people finally understand it, so that is nice.

Warner: And also frustrating, maybe?

Cliff Moers: I can't be frustrated. Our office has a mission to change the world and it's going to be ongoing, the work that we do, the education to the community. And that's the reason that I'm here. It's really a good opportunity for me.

Warner: Well, I want to ask you more about your work in just a bit, but Avery, to that question of whether CODA, the film has made any difference?

Avery Moers: I think it starts conversations and conversations are powerful. I've had a lot of people come up to me and say ‘did you see the movie? It was so cool to see sign.’ And so I think it just gives more exposure about the experience, but for culture to change and for society to change, it takes a long time.

Warner: What are you studying Avery?

Avery Moers: Right now I'm studying interdisciplinary studies.It’s a combination of special education, sociology and nonprofit. In addition to that, I recently graduated from an ASL interpreting program that was designated for CODAs.

Warner: And where do you see yourself landing after you get out of school and how closely do you think that work will be related to your upbringing?

Avery Moers: Right now I see myself interpreting for ASL. I think there's a big relationship to my upbringing. And I also think, because I didn't play the role as an interpreter growing up, I'm able to consider that for my future.

Warner: Cliff, give us a few examples of the biggest obstacles the Deaf community faces in terms of barriers in this state.

Cliff Moers: Often people will connect deaf people to a price point, a price tag. So for example, if you have somebody that you want to hire, what's the price to do that when it comes to providing the need and the accommodations for them? Are they going to need interpreters, or this or that?

It comes from a lack of knowledge of how to communicate with individuals. They have a view that it's not okay for people to be deaf. People view deaf people as if their ears are broken, as if they're a broken person. If people were to live within the Deaf community, they would see what a gift it is that we bring to the world. We have a very close- knit community. We're like a family, but in society they think everything is based on the ear and that we can't hear. And they think that what we go through is really hard and a struggle.

Warner: It does make me want to venture a guess, which is that I'm assuming the unemployment rate in the Deaf community is higher than the general population for reasons you might've outlined.

Cliff Moers: Yes. It's a very good assumption that you've made. You're right.

Warner: Avery, we talked about ASL being your first language and I think when kids talk to each other about the languages that they're studying, it's often like, ‘oh I'm taking Spanish,’ or ‘ I'm taking French,’ or German, or something. I just wonder if you wish more Americans thought, ‘I'm going to learn a language that's not my own and it's going to be ASL.’ Is that something you'd like to see more of?

Avery Moers: Yeah. I actually get a lot of comments of ‘ oh ASL seems so cool.’ It's visual. It's not spoken. It's something different. It's like a whole other type of language in its own way. So I think there is a lot of interest, but there could always be more.

Warner: There could always be more. Cliff, given that deafness has run in your family. I suppose – was there a moment when you learned that your children were hearing and not deaf, and I wonder what that moment was like?

Cliff Moers: That's a good question. I wasn't expecting you to ask that. So when my first son was born, Zeb is his name…

Warner: As in Zebulon Pike?

Cliff Moers: Yep, Zebulon. That's correct.

Warner: A true Coloradan here, folks.

Cliff Moers: Yes. And Avery is my second-born. But when Zeb was born, I thought it was just a miracle. And I was just so fascinated, looking at this infant, thinking how can this even be? I didn't even think about, is this infant hearing? Are they deaf? It wasn't even on my mind. And I do know that there are some individuals who are out there who are deaf and they do wish that their children will be born deaf, but it wasn't necessarily anything that I had hoped for.

Also, Zeb refused to use his voice. He did not speak until he was 4 years old. It was right before he actually started kindergarten. Part of that was that he didn't have to use his spoken language at home. He could hear, but he just wasn't comfortable speaking in English and he didn't have a lot of opportunity to speak English. And then he goes into preschool at 4 and was in that environment as a CODA child. They actually had to encourage him to speak in that classroom. And yet here he was bilingual and he had to manage both of those languages and he finally would speak to his teacher. And then after that, he became much more comfortable speaking English. But ASL was his first language.

Warner: Avery, does that resonate with you?

Avery Moers: I mean, my brother is older than me, so I had maybe a little bit more access to spoken language, but similar experiences. Yeah.

Warner: Did you want to go to a deaf school?

Avery Moers: Yes I did. Me and my older brother very much so. I remember begging my parents, can I please go to this school, Rocky Mountain Deaf School. And I really wanted to go. I had deaf friends who were there. I wanted nothing more than to be a part of a small community school where I knew everyone. When I entered elementary school, I struggled to adjust socially because I was just so used to being in the deaf world. It was easier for me to exist in the deaf world than it was for me to adjust to the hearing world.

Warner: Well, and how natural to want to go to school at a place where they spoke your first language.

Avery Moers: Exactly.

Warner: I want to thank you both for being with us. I'm grateful for your time.

Avery Moers: Thank you for having me.

Cliff Moers: It's great to be here to be able to share our experiences with the public and out in the community.