The Colorado Department of Transportation has a revenue problem. Over the next couple of decades, it will have an annual funding gap of close to $900 million, even as it wants to expand much needed new roads and keep the older ones safe.

So the agency has found a solution: Turn over a major section of infrastructure maintenance and management -- Interstate 70 -- to the private sector.

The planned "Partial Cover Lowered Alternative" project would remove the 50-year-old viaduct between Brighton Boulevard and Colorado Boulevard, lower the roadway and then cover it with 4 acres of landscaping. The cost: more than $1 billion, in an era of flat revenues.

"Think back to the 1990’s," said CDOT's new Executive Director Shailen Bhatt. "What you were paying for rent, what you were paying for bread, what you were paying for a car -- any of that stuff that you were paying for -- you are not paying that same amount."

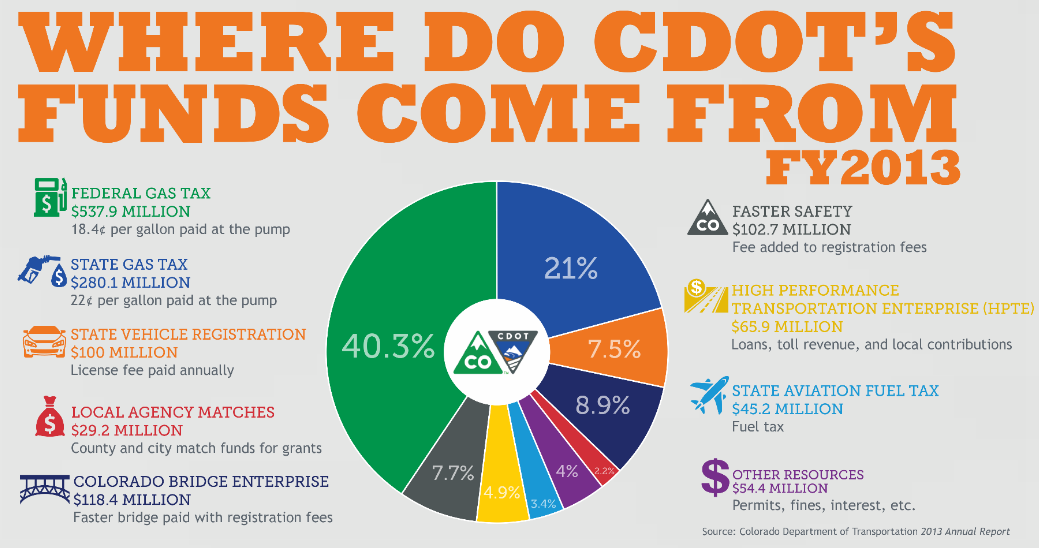

While everything from a gallon of gas to a gallon of milk has gone up in price, Bhatt said the gas tax has stayed essentially flat for two decades. That's a problem, because more than 60 percent of the agency’s annual budget comes from the stagnant tax revenue pool.

"We’re in the era of doing less with less," Bhatt said.

On top of stagnant gas tax revenues, Bhatt says people are also buying less fuel as vehicles achieve better gas mileage, so there's less product being sold to customers. Add to that the increased cost of building and maintaining roads, and it’s a triple whammy.

"You cannot come to an agency, any agency, and say, 'We’re going to constrain the resources we give you, your costs are going to increase, and yet we still want the same level of service,'" Bhatt said.

No more Band-Aids

To find an example of this challenge, look no further than the Interstate 70 East construction project in North Denver. Replacing crumbling 50-year-old viaduct with an buried roadway is the biggest undertaking in CDOT’s history.

Kirk Webb, CDOT’s environmental manager, said the agency has done what it can in basic Band-Aid fixes, but there's much more work needed.

"These joints were so deteriorated, we had to replace them. It was sort of our last fix. It’s really the reason why we need to replace this bridge," Webb said.

But that’s going to cost $1.2 billion at a time when full up-front funding remains elusive for CDOT. So to mitigate public risk, the agency has opened up bids for someone in the private sector to step in and help.

The company, or likely a consortium of companies, will specifically "finance, design, build, operate, and maintain" the roadway. Executive Director Bhatt calls it a P3, or Public, Private Partnership. And the method is becoming a larger tool in CDOT’s tool box.

"This is our way of saying look, if people don’t want a gas tax, and they don’t want a sales tax, and they don’t want to raise revenues the traditional way, then we’re going to have to look at non-traditional ways and P3 is a way to get the private sector to come in with money, and come in and assume risk. But that comes with a price," he said.

The private entity will provide funding for the project up front, with CDOT paying a set amount yearly for 30 or so years.

Unstable public funding

State Sen. Matt Jones, D-Louisville, thinks this new trend is simply a bad idea.

"It’s very close to privatizing a road," said Jones. "The problem with these public-private deals is that you basically siphon off part of the money you would have gotten, to profit to a private company. So, you actually can pave fewer roads."

Last year, Jones sponsored legislation curbing public-private partnerships in Colorado following CDOT’s 50-year contract with another consortium of companies to build, operate, and maintain a section of U.S. Highway 36 between Denver and Boulder.

That bill was ultimately vetoed by Gov. John Hickenlooper. Jones wasn't happy.

"What the transportation department needs to do, I think, is to let people know there is short funding," Jones said.

CDOT would need more tax revenue to close that gap, but a tax increase would have to come from the Legislature, which in turn finds itself constrained by the Taxpayers Bill of Rights.

TABOR places caps on government revenues. And if revenues exceed the established caps, surplus money is returned to taxpayers in the form of a refund, and not passed on to agencies like CDOT.

Because that process is fraught, says Carol Hodges with the Colorado Fiscal Institute, "The public private partnership option is one that has become more popular as simply a response to the constraints presented by TABOR."

This lack of stable public funding not only makes paying for these large scale projects hard, it also weakens the state’s bargaining power when it reaches out to potential private partners, Hodges said.

"They can’t bring more money by raising some fee or some tax or some other source of revenue which means it really does shift, or certainly has the potential to shift the benefit of the bargaining power to the private side of the equation," he said.

Bhatt says the state will maintain ownership of the road. But he acknowledges public private partnerships have gone sour in other parts of the country.

"You know, the Indiana Toll Road or a couple of projects in Chicago, where you basically turn over the project lock, stock, and barrel to the private sector and these dark sinister characters, you know, start raking basket loads of money off of the traveling public," said Bhatt.

Robert Puentes, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution in Washington, D.C. says he believes the partnerships can work, but transparency is the key to success.

"If the general public is not clear about what’s happening, not clear about the deals that are being negotiated, they're generally going to react unfavorably. And that’s not going to get the deal done," Puentes said.

CDOT hopes to secure a deal with a qualified company to build the project by late 2016. And while the agency goes through the process of picking who that will be, it’s promising public informational meetings throughout.

Editor's Note: An earlier version of this story incorrectly identified the Brookings Institution as the Brookings Institute. The current version is correct.