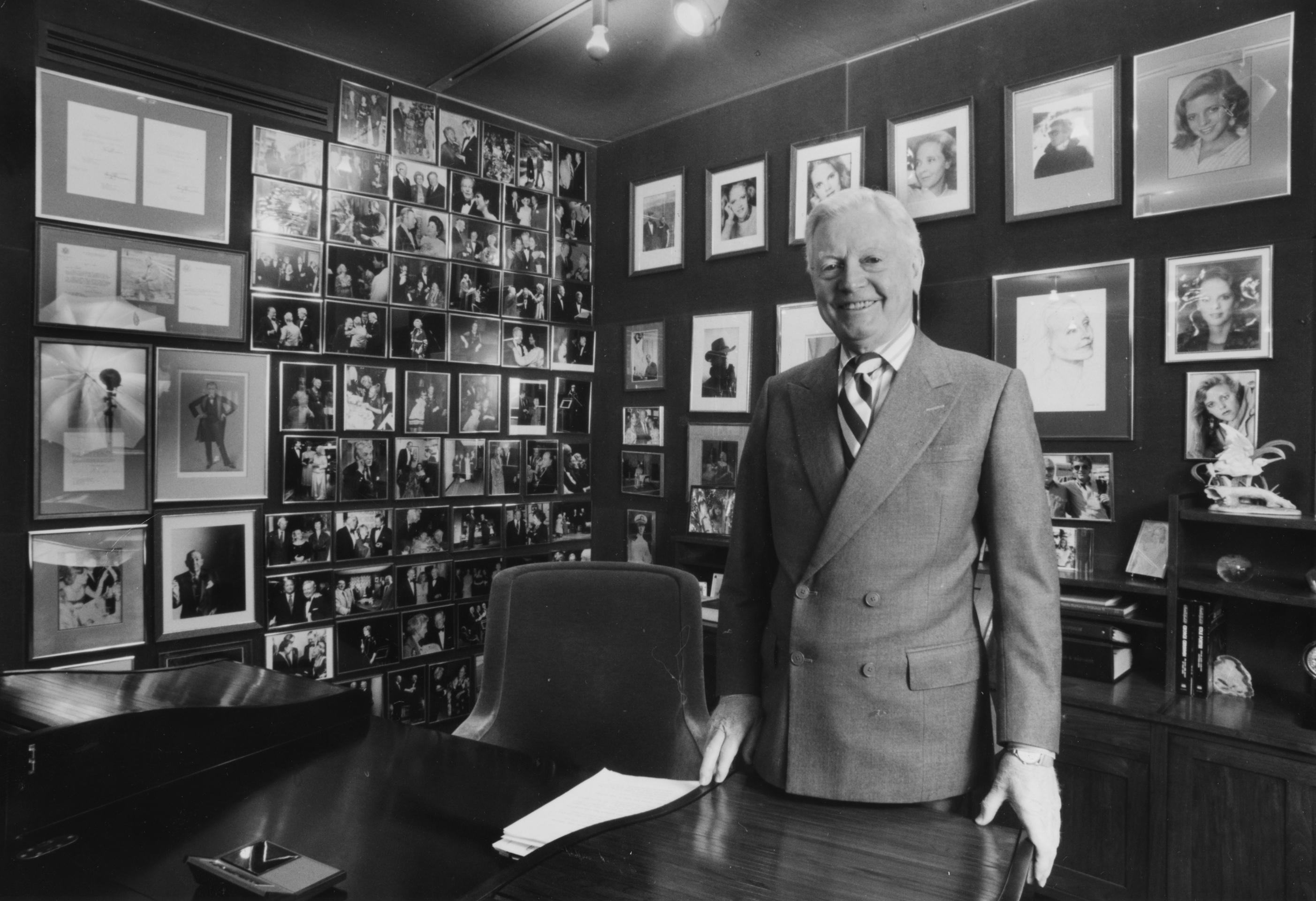

Donald Seawell, of Denver, died Wednesday at age 103.

He was a man who seems to have lived many lives in the course of just one. Seawell was an attorney, Broadway producer -- playwright Noel Coward and actress Talulah Bankhead convinced him to get into show biz. He was a diplomat -- even debated Winston Churchill as a young man. He was also a former publisher of The Denver Post.

But his most indelible mark on Colorado was the creation of the Denver Center for the Performing Arts.

In 2004, he told Colorado Matters how the idea of a arts complex at 14th and Champa came to him: "I was coming back from lunch, going to the Denver Post. I looked across the street and saw the auditorium theater," he said. "There was the arena, which was about to be torn down because they'd built the McNichols arena. There was the police building which was about to be torn down because they'd just built a new police building. And the rest of it was just a dump for old used cars and so forth.

"I thought, 'a wonderful place to create for the performing arts.' So I sat down on the curb and took out an envelope and sketched out what is now the Denver Center for the Performing Arts. Went back to the office, called the governor and the mayor and we had a meeting. Before the afternoon was concerned, I'd created the Denver Center for the Performing Arts as an entity."

"I thought, 'a wonderful place to create for the performing arts.' So I sat down on the curb and took out an envelope and sketched out what is now the Denver Center for the Performing Arts. Went back to the office, called the governor and the mayor and we had a meeting. Before the afternoon was concerned, I'd created the Denver Center for the Performing Arts as an entity."

That was in 1974. State and city leaders were thrilled at the concept, remembered Seawell.

"John Love was governor, Bill McNichols was mayor at the time. John thought it ought to be the Colorado Center for the Performing Arts. Bill thought it ought to be the Denver Center for the Performing Arts," he said.

Denver, of course, won out. Now while elected officials might’ve been enthusiastic, citizens weren’t at first. Seawell had come from The Big Apple and was seen as an outsider.

"Particularly, I wasn’t surprised by the attacks that came from all of the other newspapers. Because I was then head of the Denver Post, and naturally it drew attacks from all of the press."Here you had a New Yorker coming in and saying, we’re going to have a – the greatest performing arts center, well right here in Denver," Seawell remembered. "Obviously, people rose up opposition and I shouldn’t have been surprised.

"I remember, during the five days that the Prime Minister of Egypt went to Israel to-- which was a fantastic event. It was the first time that any Arab leader had ever gone to Israel -- so important -- but the Rocky Mountain News carried that on page five. On the front page, 'Seawell Must Go.' It went on and on, for five, the five straight days.

"So, yes, later on, I will admit that my friend Michael Howard wrote a front page editorial on the Rocky Mountain News, which said the Denver Center for the Performing Arts is the greatest thing that has happened to Denver since we got water.

"I’ve repeated this so many times, but Bill McNichols told me that the city just had a survey made by reputable poll takers, and that only 3,000 people in the entire Rocky Mountain community had ever seen a live production of any and all of the performing arts combined. And I was very happy to tell him very few years later that over a million of those 3,000 people had already seen just the theater here alone.

Seawall’s vision for the DCPA also included a resident theater company. Partly because it was difficult to draw actors from other places for contract work. But Seawell also thought talented people should know they have steady work.

"Actors have to be among the most sensitive people in the world," he said. "And there aren't enough jobs to go around, particularly if you're in New York.

I've sat in auditions, and I've-- it's painful, because every person who came to audition for a part was sure that he was exactly right and was the only person in the world that could get that part. But, you can wait for years to get the part that you want and the play might run for just one night. And you have to wait again and again.

"So, being a part of a company, knowing that you're going to work all year long, is a healing thing for an actor."

The theater business has changed since 2004 when CPR spoke with Donald Seawall. The resident theater company no longer exists. But the Denver Center still creates many new works with what can now be more flexible casting.

Another milestone in Seawall’s career was the mounting of Tantalus, John Barton’s 9 play retelling of the Greek Epic Cycle, which opened in 2000 in Denver and toured the UK. It may have seemed risky, but Seawell didn't see it that way:

"I wouldn't use the word risky for this reason: We knew what we were doing, we knew how much it would cost. We knew it was bound to lose money. Why? Because it was the longest play in the entire 2,500 year history of the theater.

"I wouldn't use the word risky for this reason: We knew what we were doing, we knew how much it would cost. We knew it was bound to lose money. Why? Because it was the longest play in the entire 2,500 year history of the theater.

"It started out as a 22 hour play. It was cut down to 15, and in some instances 12, but that's still the longest.

"We knew we'd have to rehearse for 7 months. And we knew we could only run it twice a week. It's impossible to charge enough to get the money back. But it's something we felt had to be done.

"Originally, it was to be done by six groups, a consortium of theaters. One by one, the others starting falling off. Why? Money. It ended up that we did it, or it wasn't going to be done.

"We did it in cooperation with through our Shakespeare company. They didn't put up any money, but they did supply some of the actors. We went to England through them after it played here.

"But it cost us, oh not quite the equivalent of one season of theater here. I think it did more for this theater than we've ever had."

"But it cost us, oh not quite the equivalent of one season of theater here. I think it did more for this theater than we've ever had."

Even so… Donald Seawell told us he was rarely satisfied.

"There's something at the masthead of the Denver Post: 'There is no hope for the satisfied man.' And I feel that particularly as far as the theater and our work is concerned. Never will I be satisfied. If I'm satisfied, I ought to be kicked out of here immediately."

And then there was the time that singer and actress Marlene Dietrich took a bath in his Paris hotel room.

"Well after we had liberated Paris, I was sent in as – briefly as Acting Ambassador to France.

"Instead of opening the Embassy residence, I had a suite at the Ritz. And that was a very, very cold winter after we – and we had hot water at the Ritz we didn’t have anywhere else in Paris. So people who – like Marlene and others, would come to my apartment to get a hot – hot bath after they returned from the front. And so that’s the story, Marlene used to come in to get her hot bath, but unfortunately we didn’t take it together."