If you’ve driven along the busy stretch of I-25 south of downtown Denver you’ve likely seen it: a tall, canary yellow structure that seems to twist and morph as you pass it by.

Gwen Chanzit, curator emerita of modern art at the Denver Art Museum and director of museum studies at the University of Denver, knows exactly what you’re talking about.

“[The artist] understood that people would see this sculpture from a very busy highway, so he realized that as you went by in a speeding vehicle, the sculpture would change shape,” Chanzit said.

The bright landmark sculpture has many nicknames — “What’s up with the noodle sculpture?” Kethry Warren asked Colorado Wonders — but its real name is “Articulated Wall” and the artist who dreamed it up is Herbert Bayer. The 85-foot-tall artwork was Bayer’s final completed commission before his death in 1985.

Warren associates “Articulated Wall” with noodles “because it looks like a piece of bow-tie pasta,” she said in an email. “I've heard other people refer to it as more French-fry-like, but bow tie pasta just seemed to fit better.”

Beyond French fry and noodle analogies, people have also compared the twisting yellow step sculpture to a stack of cheese sticks and Juicy Fruit gum packs piled on top of each other. Your interpretation will likely depend on the angle from which you view it and how hungry you are that day.

“Because people have dubbed it various names, that means they're looking and I suppose that's a very good thing,” said DAM’s Chanzit, the go-to expert on the sculpture.

“Articulated Wall” is comprised of 33 prefabricated concrete slabs, all slightly askew of each other and held together by — get this — an aircraft carrier refueling mast that runs down the center.

Chanzit said Bayer understood that people viewed outdoor artwork differently in the 1980s versus “the times of the Renaissance, when you had a pedestrian walking along slowly and seeing sculpture” in a plaza. According to the artist’s own writings, he believed the highway was “an issue worth the attention of an artist.”

Time marches on, however, and in 2018 you’ll likely have a better view of “Articulated Wall” from the light rail line that runs right behind it. The sculpture was installed in 1985 and I-25 has been rebuilt and moved around, especially with the T-REX Project in the early 2000s. So, “it's not quite as visible as it had been in its early days,” Chanzit said.

Are you ready for another surprise? Denver’s “Articulated Wall” isn’t alone and it’s not the first.

The original is in Mexico City. Bayer designed it for the 1968 Olympics. It looks like Denver’s, except it’s more than 20 feet shorter. The developer of the Denver Design District commissioned Bayer to make the Denver look-alike.

Chanzit said she’s “100 percent sure” that, had Bayer lived, he would have built a park around the sculpture “with berms and recesses and a place for people to relax,” very much in contrast to the concrete steps and pedestal it sits on in the back parking lot of the Denver Design District.

Technically, the sculpture is on private property but it’s owned by the Denver Art Museum.

Dan Cohen, the development manager with the design district, gets a view of “Articulated Wall” every workday from his office window. He explained that they don’t restrict people from seeing the artwork up close, but there is often a security guard in the parking lot, monitoring to make sure people are being safe and respectful.

“We love having this icon on our property,” he said.

Bayer was born in Austria in 1900 and later enrolled in the famous Bauhaus art school in Germany at the age of 21. Chanzit considers him the Bauhaus exemplar.

“The Bauhaus said that you should practice all the different disciplines and integrate them into a total design.”

He indeed did many things: graphic design, architecture, painting, sculpting, typography, photography, art direction and the list goes on. It was his exhibition design skills that first brought Bayer to New York in the late 1930s, to design several major shows for the Museum of Modern Art. Bayer then emigrated to the U.S., but he was unhappy in Manhattan, Chanzit said.

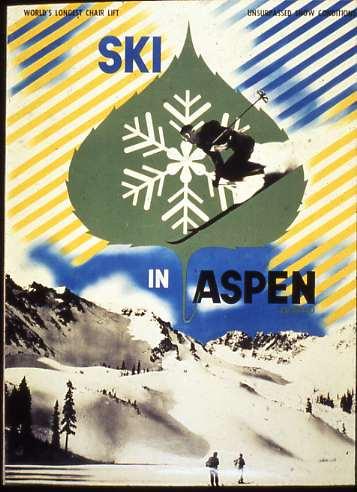

About that time, businessman Walter Paepcke, who was head of the Container Corporation of America, saw Bayer’s talent. Paepcke wanted to transform Aspen, Colorado, from a relatively unknown mountain town into a cultural and intellectual destination. He recruited Bayer to help do just that and the artist relocated in 1946.

Paepcke founded the Aspen Ski Company and Aspen Institute. Bayer designed for both organizations, as well as early ski advertisements and menus.

Aspen was where Bayer could fully realize his total design philosophy, Chanzit said. It was something he learned while at Bauhaus. It’s an integration of the fine and applied arts — architecture, decor, artwork, graphic design, advertisements — and all design aspects are in harmony.

“Aspen was really like a Bauhaus dream in the sense that you took every aspect of life and you designed well for it,” Chanzit said.

His influence on Aspen was immense: “His legacy there is a way of thinking.”

When Bayer relocated to California in the ‘70s for health reasons, Chanzit said he called it a “tragedy.”

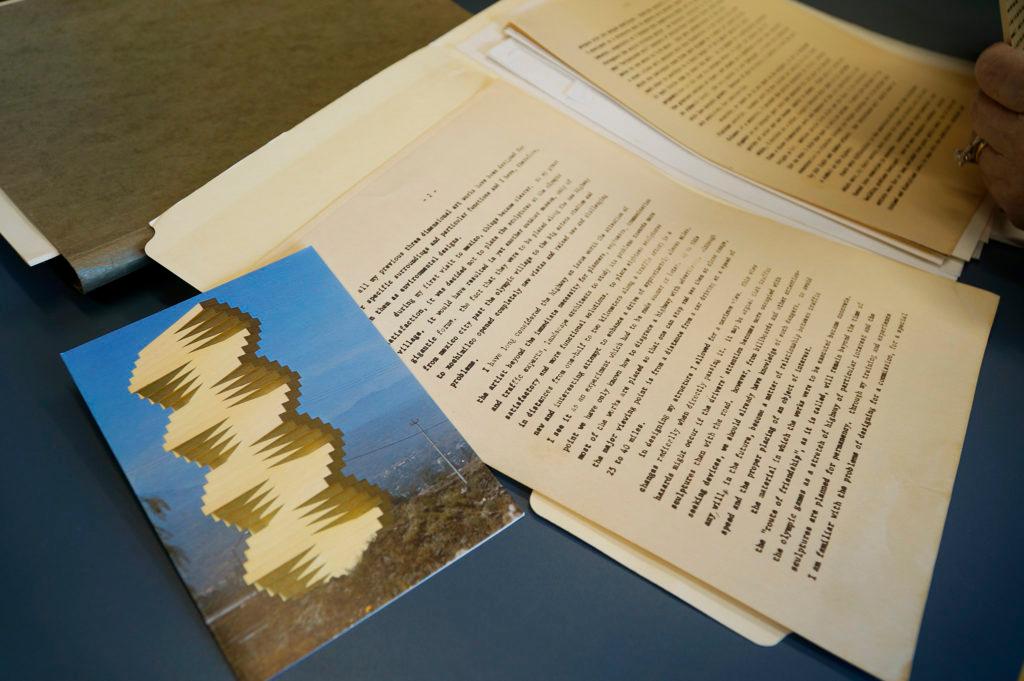

For years, Chanzit oversaw the Denver Art Museum’s Herbert Bayer Collection and Archive. The museum has given much of the archive to the Denver Public Library’s central branch to make those materials more accessible to researchers and the public. The archive includes letters, journals, photographs, tear sheets and speeches Bayer wrote.

The senior archivist with the library’s Western History and Genealogy Department, Abby Hoverstock, said they’re still organizing the archive, but it should be available for study in early 2019.

Hoverstock nodded in agreement as Chanzit said she hopes making the archive more accessible will lead to a deeper understanding of the breadth of Bayer’s work beyond the widely viewed “Articulated Wall.”

Correction: “Articulated Wall” is comprised of 33 prefabricated concrete slabs. This story has been updated to accurately reflect the number of slabs in the artwork.