Updated 12:17 p.m.

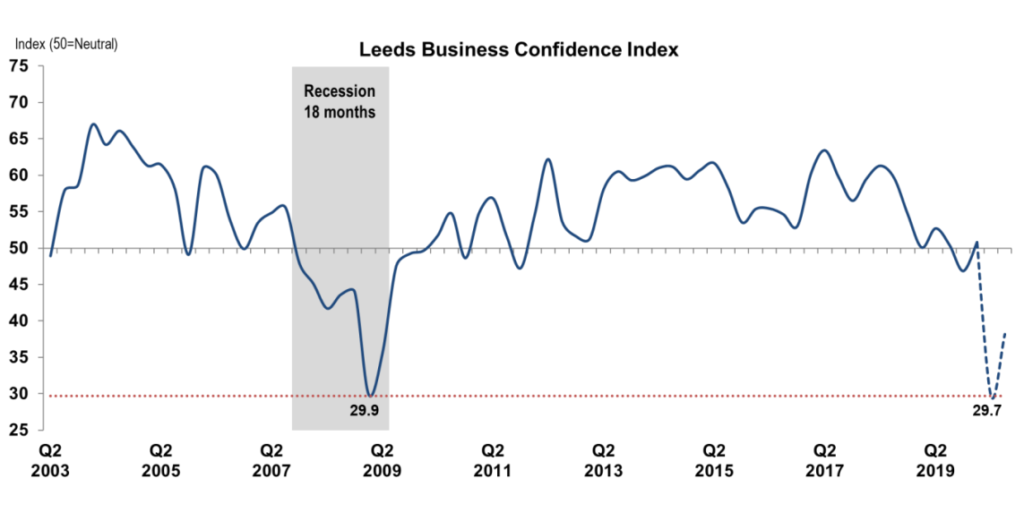

Optimism among Colorado's business leaders is at its lowest level in 17 years thanks to the COVID-19 outbreak. That's according to a quarterly survey by researchers at the University of Colorado Leeds School of Business.

Their 2020 second-quarter report says nearly 9 in 10 of business leaders who responded to the survey say the new coronavirus and its effect on the economy is their biggest concern.

The measure of confidence in the economy is the lowest on record since the survey began in 2003, according to Brian Lewandowski, the executive director of the Leeds Business Research Division. The sharp decrease exceeds anything seen during the financial crisis and the recession that followed, he said. “This event came on us so quickly,” Lewandowski said during a conference call with journalists.

The quarterly survey may not fully account for just how negative sentiment could get as damage to the economy from shuttered businesses and plunging consumer spending becomes more pronounced. The survey, conducted between March 3 and March 20, doesn’t reflect a full month of the stringent social distancing measures put in place roughly two weeks ago.

“My expectation is that we will see things get worse before we see it get better,” Lewandowski said. “April could be the worst economic data month.”

Confidence is souring as Colorado’s jobless claims skyrocket. They had hovered near all-time lows for years. The tourism and service industries have been decimated by the sudden shock of mandatory business closures and restricted travel.

Restaurants are the most vulnerable in the near term, Lewandowski said, noting the low-margin nature of the industry. Failures are common even in the best of times, he said.

“When we see an event where businesses are forced to close to dine-in customers, that’s going to severely impact the viability of these companies,” Lewandowski said.

Colorado consistently ranks in the top five destinations of interest in the U.S., and will see a big impact from the downturn in tourism for both domestic and international travelers, according to Richard Wobbekind, Lewandowski’s counterpart at the Leeds Business Research Division. For that industry to fully recover, the outbreak will need to be under control beyond Colorado’s borders.

“Tourism needs a total healing, not just a statewide healing,” Wobbekind said.

The overall economy was on strong footing when the pandemic struck. Still, confidence within Colorado’s business community had been teetering.

Trade wars, impeachment and monetary policy all contributed to concern that a downturn was inevitable amid one of the longest economic expansions in U.S. history. Optimism levels as measured by the survey were hovering just at or below the neutral mark for the past two years, according to Lewandowski.

“What was interesting was how well the economy performed despite the uncertainty,” Lewandowski said. “Business leaders had gotten used to it – that has surely changed now.”

Many of the respondents say they are hopeful the economy will rebound in the third quarter of the year relative to the second quarter, but the optimism is muted, Lewandowski said.

So far, high-wage segments of the economy haven’t seen the types of mass layoffs afflicting retail and recreation, Lewandowski noted. If the timeline for containment of the virus set forth by President Donald Trump and other government officials holds, pent-up demand could help boost the economy during the third quarter, Lewandowski said.

“It’s important to remember that a majority of Americans still have their jobs… they just don’t have as many places to spend those dollars,” he said.

Overall, the unprecedented scope of the epidemic leaves business leaders and consumers without a lot of guideposts to navigate the crisis. Wobbekind expects a significant loss of business infrastructure and double-digit unemployment during the second quarter. It could take three years to recover all the jobs lost, he said.

It’s impossible to pinpoint the timing of a global pandemic, but there were signs earlier in the year that were largely missed, Lewandowski said.

“Perhaps we should have seen when the cases really started to spike in China… that this could be a pandemic that has far greater impacts on the U.S. economy than I envisioned,” he said.