Let's face it, outside of the health of our loved ones, all we really care about is when coronavirus stay-at-home orders are gonna be over and which numbers will tell us that. That requires us all to become amateur epidemiologists.

So we asked the experts to offer a guide.

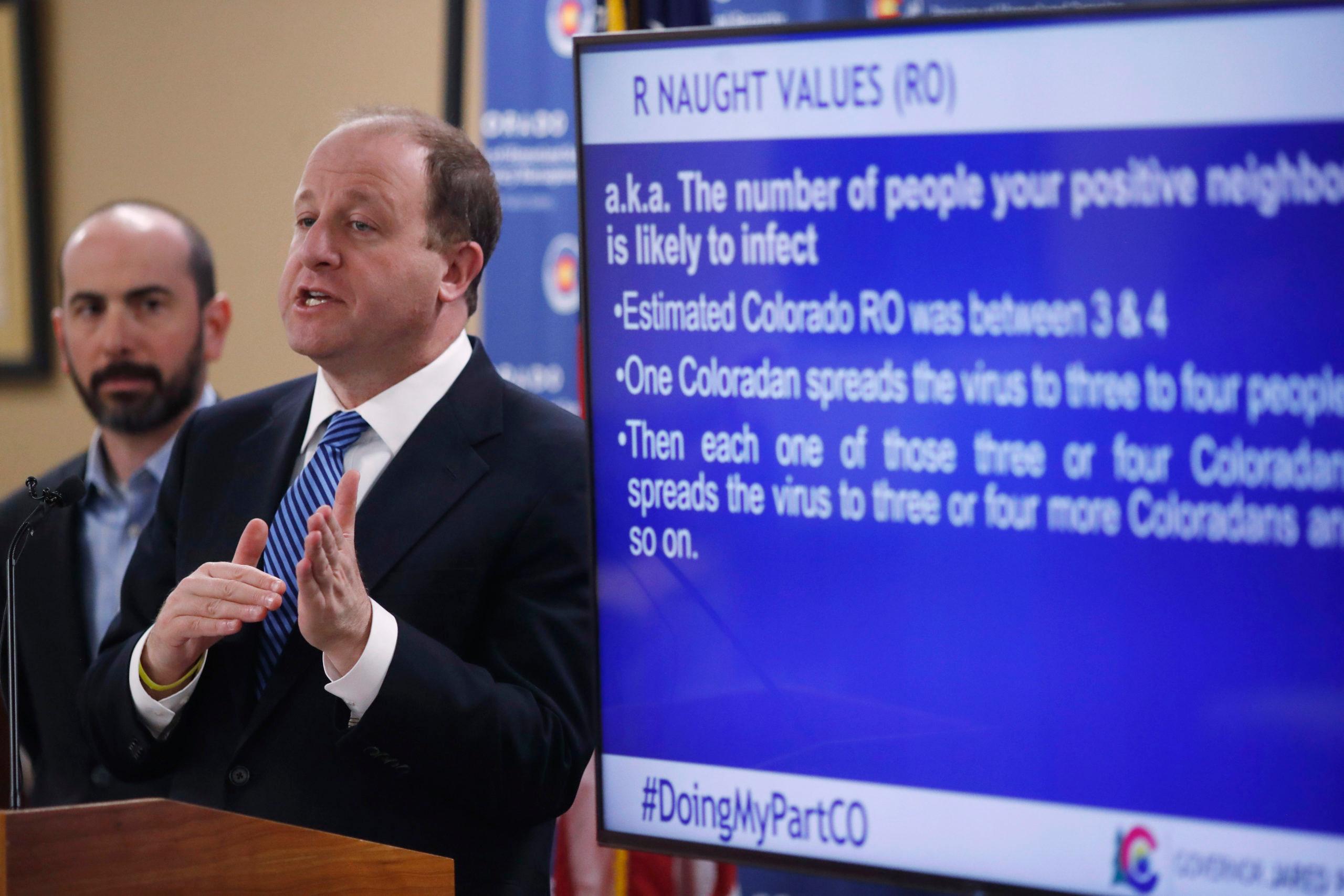

First, some caveats: One of the most frustrating challenges of COVID-19 for experts, decisionmakers like Gov. Jared Polis, or even amateurs who just want to sound smart on a conference call has been getting good data. We’re all flying blind, or at least impaired, as testing is extremely limited in Colorado and across the country.

That forces you to look beyond total infections or infection rates. But all of the other datasets have issues too.

Also, any dissection of the statistics has to include this: It is all up to us. If we declare victory prematurely, remove our masks, return to work, have a block party or go to the park for a pickup softball game, all bets are off. The virus could be re-energized, find new hosts and spread through the population with fatal effects, sending all of these stats through the roof.

To paraphrase Polis: Stay at home.

Use this data as a guide for speculating on when he might declare Colorado back open for business, but don’t use it to try to get ahead of him. You might just kill someone you love.

To the numbers...

Positive Test Numbers

There have been 6,510 confirmed positive cases through Friday afternoon. This is the total number of people known to be infected with COVID-19 in Colorado. Well, not really. The state has lumped in a small number of cases that are “epidemiologically-linked,” meaning there was some evidence besides a test that suggested the person was infected.

More importantly, case numbers are influenced by how much testing is going on and that’s extremely limited and inconsistent across the state's counties. Just more than one-half of one-percent of Coloradans have actually been tested for COVID-19.

State officials estimate that as many as 10 times more people have the illness. They also admit that is a guess.

“We do acknowledge that the limitations in testing provide us with a lack of true clarity on what is happening,” said state incident commander Scott Bookman.

The state, Bookman said, lacks the supplies needed to collect test samples, like personal protective equipment and swabs. Hospitals have also reported that they have limited reagents, the chemicals needed for testing, and so some large hospitals, like UC Health, still can’t test everyone that probably should be tested.

Deaths

There have been 250 deaths classified as COVID-19 related so far in Colorado. That number has doubled since March 30 when the state reported 126. That seems like it would be a pretty certain statistic, but not as certain as you’d think. It’s not always clear what the person died from, and the cause of the deaths can be miscategorized in the hospital.

“Deaths are likely to be an undercount,” said Glen Mays, a professor at the Colorado School of Public Health on the Anschutz Medical Campus.

He said it’s not always possible to get a confirmation of COVID-19 infection prior to the death occurring.

Deaths outside the hospital are even more likely to be miscategorized. Are all coroners, physicians or medical examiners doing post-mortem COVID-19 tests to determine if an elderly person with a cold actually had the coronavirus before they suffered kidney failure or some other cause of death? Maybe, but given the lack of test availability, it seems unlikely.

On top of that, even tracking deaths by day to look for trends is a challenge. The state acknowledged Thursday evening that death reports from counties are sometimes delayed by days, meaning they don’t show up in the reports posted here by the state each day at 4 p.m. It all smooths itself out in the totals, but that doesn’t help in looking for trends.

So what is a good way to measure the spread of the coronavirus?

Hospitalizations

This is the number of people with severe enough symptoms to require admission. “The hospitalization, counts and rates, is probably the best single number we have,” Mays said.

It’s still an imperfect measure, in part because of how Colorado is tracking hospitalizations -- cumulatively. “And so it doesn't tell us how many people are currently in the hospital,” Mays said. “And it's not factoring in the rate of discharge, the length of stay.” Those would be important metrics for knowing if the state’s hospitals are exceeding capacity.

Still, here’s what the hospitalization data does tell us about COVID-19 in Colorado.

CPR News reviewed raw data from the state health department. It shows that new COVID hospitalizations peaked on April 2 with 111 new hospitalizations. And there appears to be a significant decline in hospitalizations in recent days, averaging only about 35 new daily hospitalizations between April 4 and April 8.

But beware: The same questions of data collection surrounding deaths also apply to hospitalizations. The state isn’t even sure they are reporting accurate numbers each day. Those smaller daily admissions numbers reported in the last few days will balloon if some hospitals have not yet reported.

The state says there’s no single statistic that can tell you everything.

“I don't think that's an appropriate way to look at it,” said Mike Willis, director of the state Office of Emergency Management. “You have to look across a broad spectrum of metrics and aggregate them in together to get an understanding of the trends in the state.”

If you track hospitalizations using a seven-day average you might be able to watch the trendline and see if we are heading up, or down. So far, the hospitalization data appears to show that the extreme measures put into place in Colorado are having their intended effect.

But again, that all changes quickly if the public stops following the social distancing guidelines before the threat has passed.

“We're certainly not out of the woods yet,” said Mays. “But it does look like we're getting some positive feedback that the policies that are put in place are helping to slow the rate of growth and transmission, and if we can stay the course we can likely avert some of those worst-case scenarios.”