The blizzard that dumped snow along the Front Range in March helped Colorado nearly reach its average snowpack for the winter, federal data shows.

But last year’s historically dry weather means that streams are likely to run lower than normal, potentially restricting the amount of water some consumers can use, experts said Thursday.

“We don't ever like to see back-to-back below average years,” said Keith Musselman, a hydrologist with the University of Colorado Boulder. “Those years can piggyback on each other to build into drought conditions. And that's always the concern.”

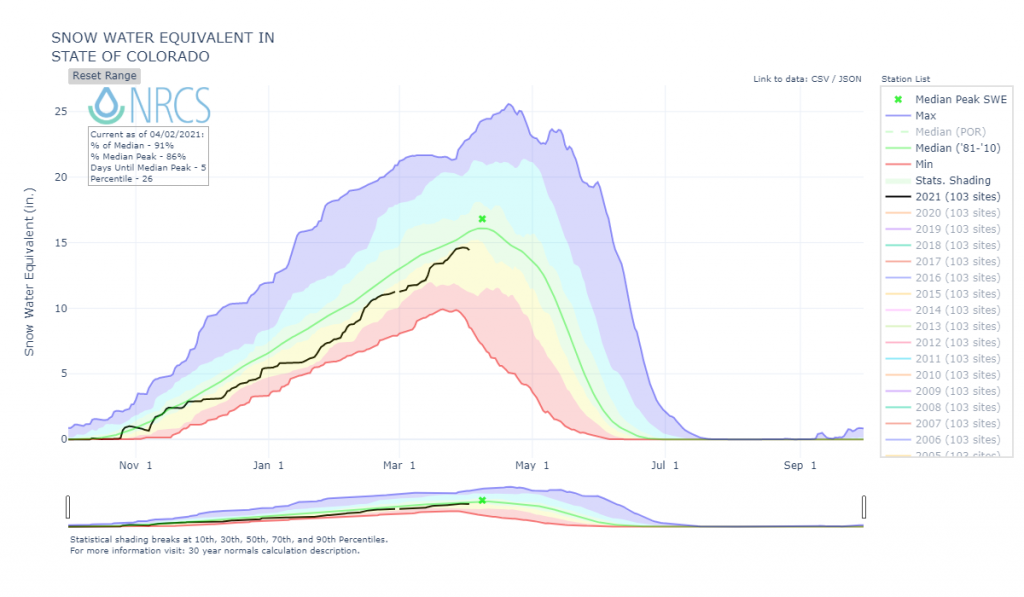

State snowpack levels were at 93 percent of the average for the state as of April 1, according to the Natural Resources Conservation Service. Snowpack is the total seasonal accumulation of snow on the ground.

That figure was higher in 2020 when the snowpack was above average for the same date. Still, a dry spring and hot summer made it one of the driest years on record and created drought conditions that sparked some of the worst fires in state history.

The outlook for snowfall at the beginning of the year looked dismal. But a string of strong snowstorms, including March’s blizzard, pushed state numbers back on track. Areas east of the Continental Divide had above average snowpack, but the Colorado River Basin on the west was below average.

Scientists can use the snowpack to predict the amount of water that will run through streams and river channels, said Ben Livneh, an assistant professor in civil engineering at CU Boulder. Although the snow will help with the drought, those streams are still expected to run below average, he said.

A major factor of this is the soil, he said, which has remained dry since last year. As the snow melts down the mountains, the water will first have to replenish the soil before it continues toward the reservoirs.

“Less of that snow is going to melt into the streams, theoretically, and make it into those stream flows, which would then be provided to water users,” said Brian Domonkos, supervisor of the NRCS Colorado Snow Survey.

That lack of water would most likely affect agriculture and irrigation in the western slope, which is currently under the most severe drought in the state, according to data from the U.S. Drought Monitor. It could potentially lead some cities to set limits on water use or encourage residents to conserve water, Livneh said.

Another significant issue is that snowpack is melting earlier in the year as the planet warms, Musselman said. That reduces the amount of water available later in the year, drying the soil and vegetation and increasing the risk of wildfires, he said.

Forecasts don’t predict substantial precipitation before most of the snow melts this summer, Livneh said. But there is still the potential for recovery.

“The next couple of weeks is really critical,” he said. “If we can build more substantial snowpack, a longer lasting snowpack, that would actually help us a lot.”