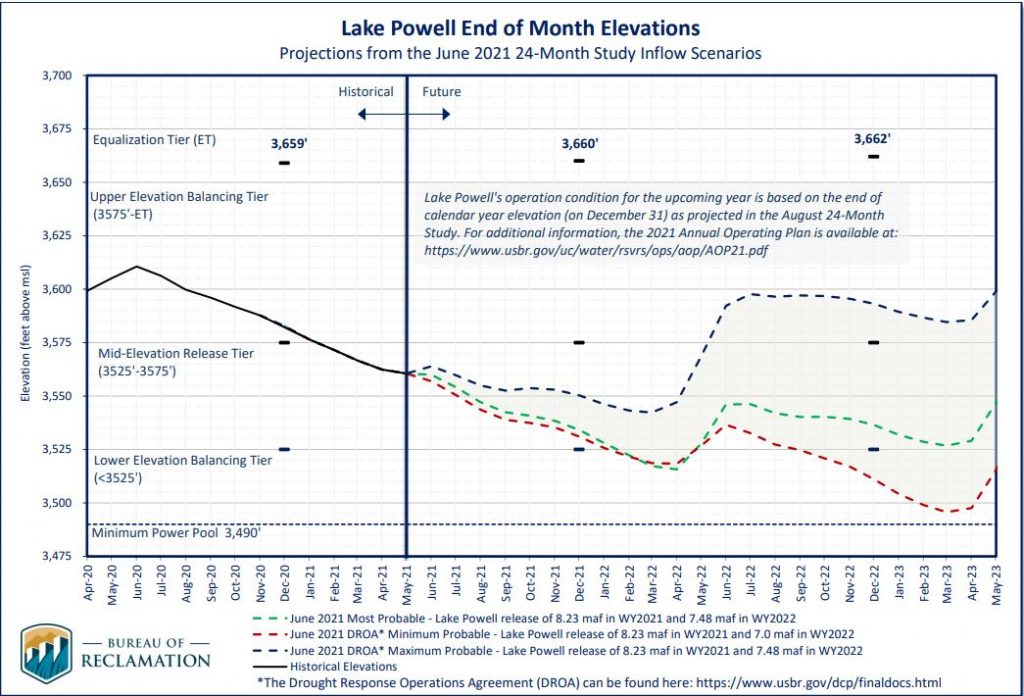

Lake Powell’s water level is the lowest it's been in decades, and the latest 24-month projections from the Arizona and Utah reservoir show that it’s likely to drop even further — below a critical threshold of 3,525 feet by next year.

A 20-year megadrought and a hotter climate has contributed to shrinking water supplies in the Colorado River. If Lake Powell’s levels continue to dwindle, it could set off litigation between the seven states and the 40 million people that all rely on the Colorado River.

“This is really new territory for us,” said Amy Ostdiek, deputy section chief of the federal, interstate and water information section of the Colorado Water Conservation Board.

Lake Powell is the second-largest artificial reservoir by volume in the United States. It sits on the border of Utah and Arizona and is filled with Colorado River water. It was created as a storage bucket to help states in the upper Colorado River Basin — Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming — meet their downstream water delivery obligations to the lower basin, including Mexico, Arizona, California and Nevada under a 100-year-old water-sharing agreement.

Lake Powell is where that water is released. When those levels are in good shape, Ostdiek said it keeps the lower-division states from suing the upper-division states. If Lake Powell’s levels drop below 3,525 feet, it would make it more challenging for Colorado and the other upper-basin states to meet their compact obligations.

“It could potentially lead to seven-state litigation, which we’ve never seen before on [the] Colorado River,” Ostdiek said. “Which would create a lot of uncertainty. It would probably be a very long, drawn out process.”

States agree Lake Powell must stay above certain level

Ostdiek said it’s a “universally-accepted goal” among the seven states to avoid that situation. That’s why they agreed to the 2019 Colorado River Drought-Contingency Plan, which includes the provision that if Lake Powell drops below 3,525 feet, the upper-basin states and the Bureau of Reclamation have a plan in place to send more water to Lake Powell.

Those meetings are happening. Ostdiek said the upper-basin states have recently switched to planning mode due to the low water levels forecasted for Lake Powell. The plan to protect Powell could involve releasing water from upstream reservoirs of Flaming Gorge, Blue Mesa, and Navajo in Utah, Colorado and New Mexico.

But the hope is to avoid the need for that plan by keeping Powell above the 3,525-foot threshold.

“We really just want to be able to control our own destinies on the Colorado River,” Ostdiek said. “Frankly, putting it in the hands of a judge is not doing that. We don’t know what would happen.”

Ostdiek said that there’s already been “really, really painful [water] cuts across the state,” because of the prior appropriation system— Colorado’s legal framework that regulates surface water and tributary groundwater use through a priority system of who owned what water rights first.

Ostdiek said junior water rights users are getting shut off, which means those who have acquired water rights more recently are beat out by those who’ve owned them for longer. She said the state's southwest corner is a particularly painful spot for shutoffs right now with ongoing extreme drought conditions.

The drought response plan from the upper-basin states will not be finalized until the Bureau of Reclamation's April 24-month inflow forecast shows that it’s most likely that Lake Powell will fall below 3,525 feet within a 12-month period.

A press release from the Colorado Water Conservation Board acknowledges that the Secretary of the Interior has the discretion to take emergency action if there is an imminent need to protect Lake Powell from dropping below 3,525 feet.

Editors note: This story has been updated to correct the last name of Amy Ostdiek.

- In Fountain, Colorado, There’s Plenty Of Room For New Homes. But There Isn’t Enough Water

- The Front Range May Have Gotten Soaked, But Half Of Denver’s Water Supply Comes From The Drought-Stricken Western Slope

- Dry Soils And Drought Mean Even Normal Snowpack Can’t Keep Up With Climate Change In The West