Carlee Taga used to walk up to people in bars and concerts, engage them in a conversation about safe sex and hand out condoms. It was her job with a state health department.

People would thank her, appreciate what she was doing and say, “but I really needed you when I was 15 or 16.”

So Taga went back to college to become a secondary school science and health teacher.

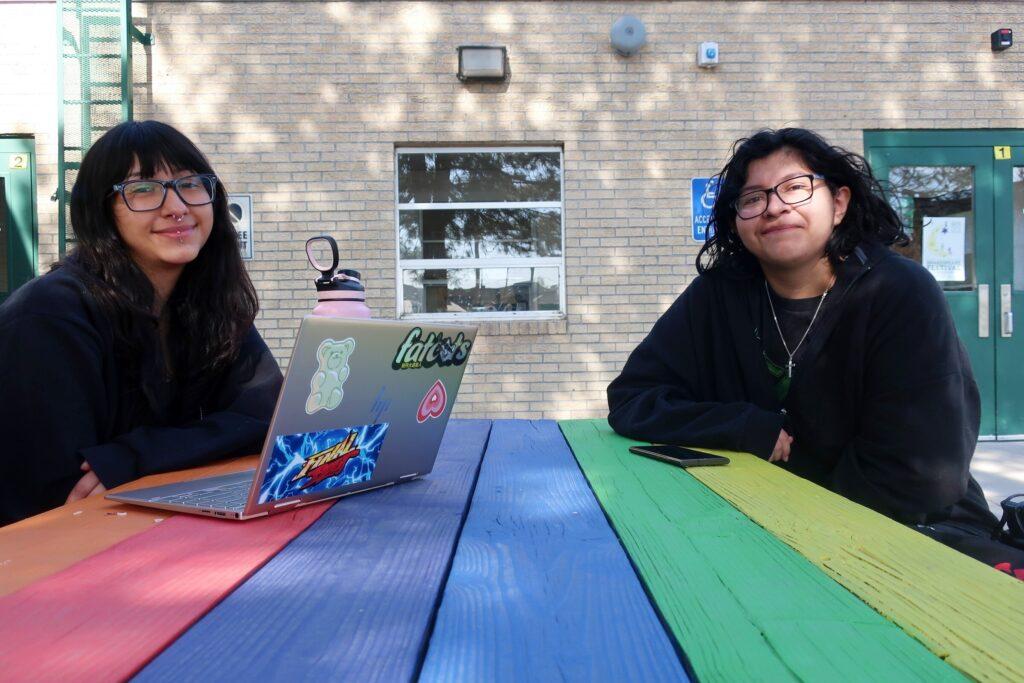

She knows sex education works. Research shows it leads to fewer unintended pregnancies and sexual transmitted infections. But what’s made the biggest difference in her North Denver school AUL Denver has been the peer sex educators. Students at the school don’t always feel comfortable asking Taga, 31, questions.

“It's different when you're 15 and you're going through things and you want peer support to say, ‘I'm going through that too,’ ” she said. “The peer education group has given students the tools they need to have those conversations, give each other the resources and the information to help empower their friends, to make good, healthy decisions in their lives.”

If a peer educator doesn’t know the answer, they tell the student they’ll get back to them with the proper information. Studies have shown teens in peer educator programs scored significantly higher on knowledge of sexual health issues, ability to refuse risky sexual situations and reported more opportunities to talk to friends about sex and birth control and setting boundaries with sex partners.

So, what do the teens have to say about what they’ve learned in sex education?

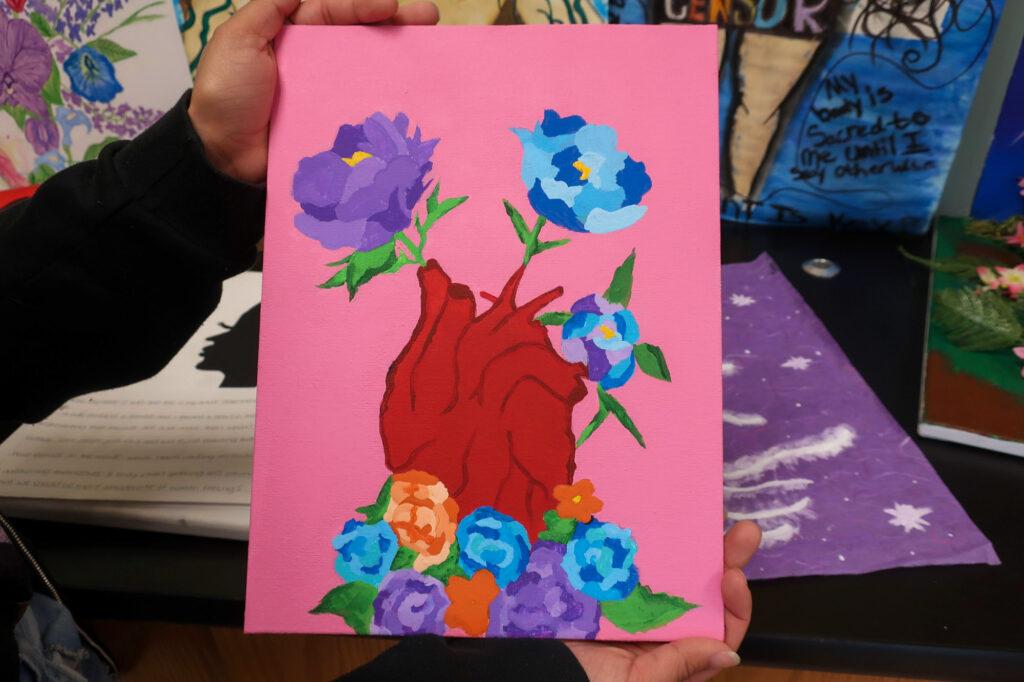

Recently, some of the peer educators and other students were part of a special workshop, moderated by two teens who were part of a Trailhead Institute project aimed at making students' lived experiences the focus of sex education. The students had to make a piece of art on an aspect of sex education – from school, family, church, friends, the internet — that changed how they see the world.

As the workshop starts, students look at paintings from an Indigenous artist. It’s a colorful depiction of ‘desire’ spilling over body and time.

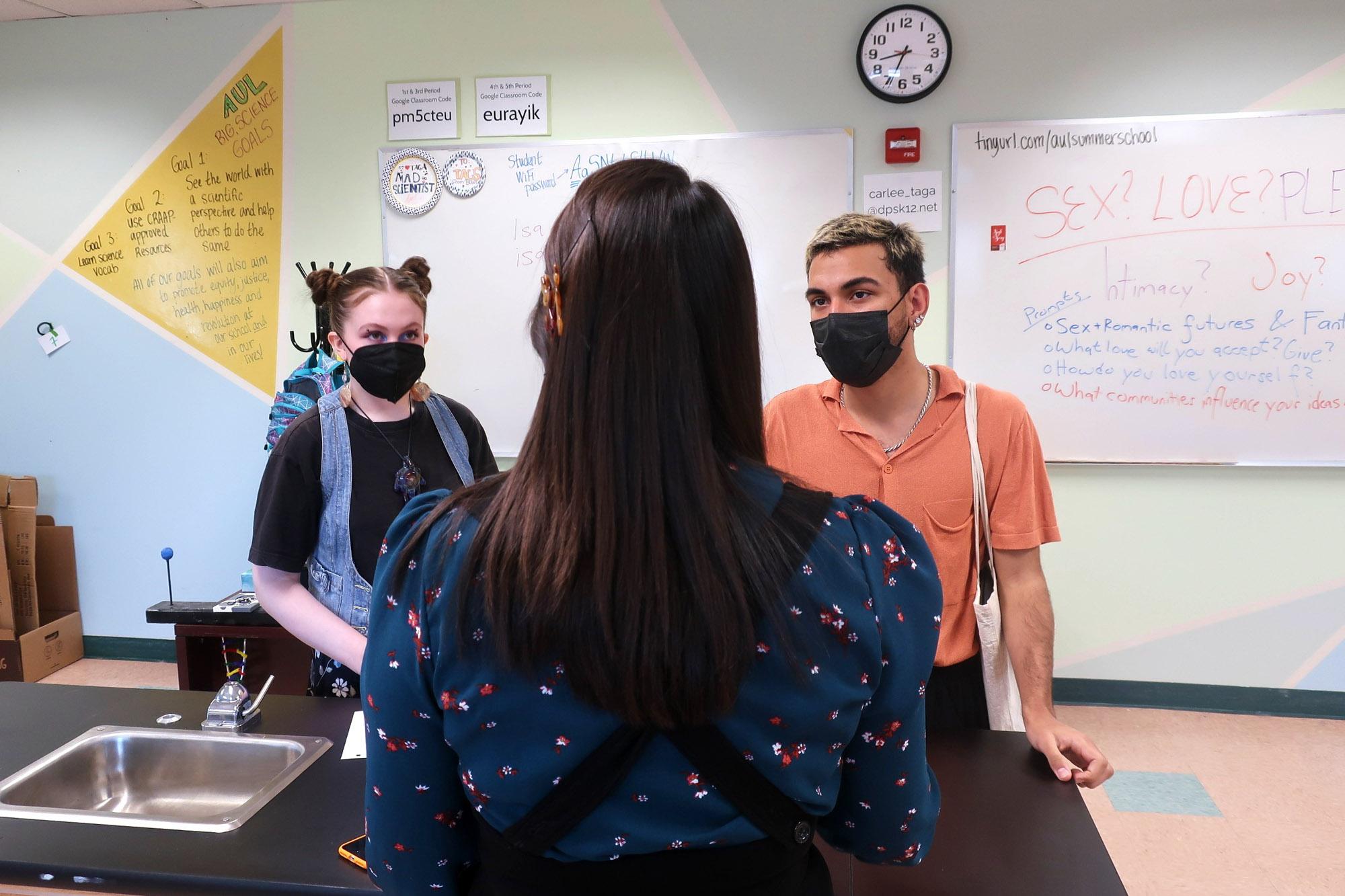

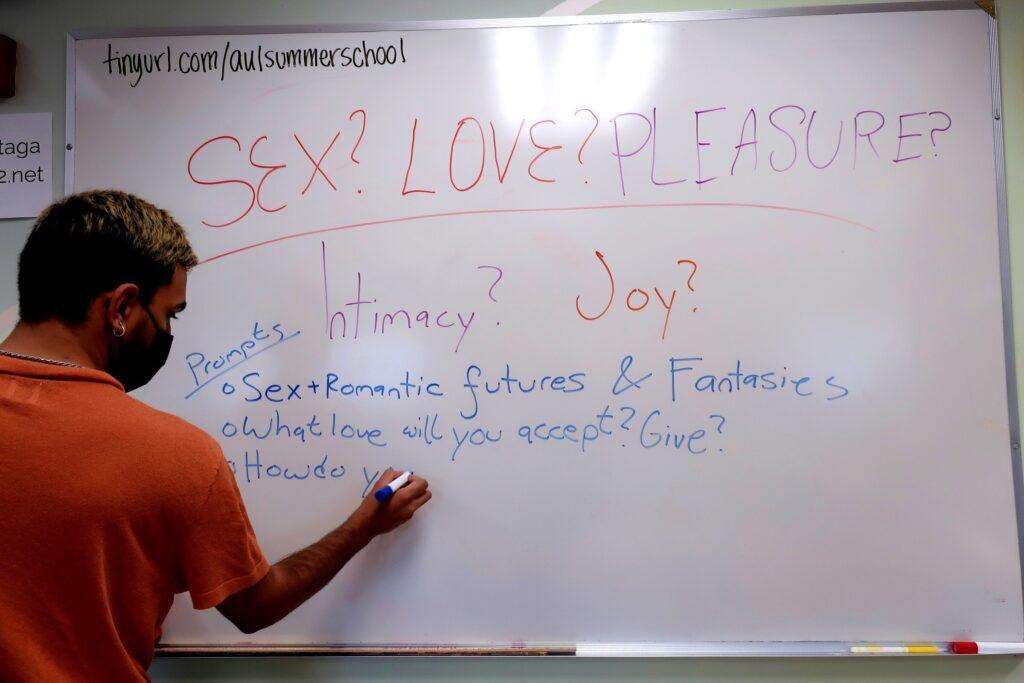

“I love them a lot because they center brown bodies,” teen workshop moderator Issa Hussein tells the group. He said a lot of adult-focused sex education is very fear-based. He writes several words on the board: Sex, love, pleasure, intimacy, joy — words students might want to consider as they do their projects.

“I want to draw part of my body on how I see myself and on the other side and how reality (media) says what my body should be,” Devin Esquibel tells the group.

Like a lot of boys, he was introduced to porn at a young age.

“I think that’s really what skewed my perception on sexuality because from 14- 12-years-old you’re looking at bodies that aren’t the same as yours,” Esquibel said. “Penis sizes look completely irregular and you start to doubt yourself and your ability because of it.”

Several weeks later, the projects are finished. Body image is a big theme. Teens are inundated with unrealistic body images through social media and online porn.

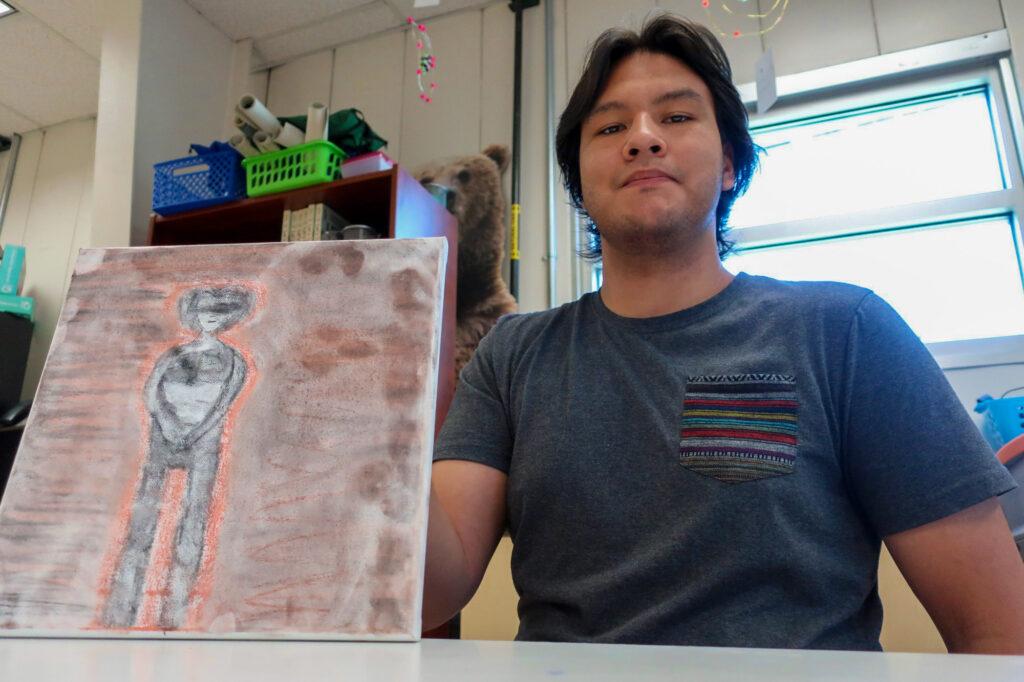

Esquibel holds up a charcoal drawing of a body. The hands cover its genitals and the chest is blacked out, “because of my fear of my body and the way I looked naked.”

At 17, Esquibel began cutting back on social media and pornography and — the sex education class also helped him, “in the sense of not fearing what my body looked like and knowing that there’s many different types,” he said. But he sees the problem of porn distorting boy’s views of sex getting worse, especially if there’s no one — or no class — to counter those views.

Taga talks about porn in her classes, how it sets an unrealistic standard for what bodies look like for what consent looks like for what safety looks like in real life sex.

“I tell my students behind the scenes, there are STI screenings every week. There's long talks about what is OK and not OK to happen on camera, but none of that is what is sexy enough to make it on screen,” she said.

“It blows my student's minds every time when I say the same CGI that makes Iron Man fly is used in pornography to make things appear in a certain way.”

Not all students in Colorado get this kind of sex education. Whether they get it at all varies widely by school and district

If schools in Colorado choose to teach sex education, state law dictates that it must be science-based, comprehensive and inclusive. But districts and schools don’t have to teach it. It’s an elective. Parents can also opt their children out.

Taga said it’s really left up to administration, staff and teachers to decide whether sex education should be required, or even offered, at their school. What’s offered varies widely between districts and even between neighboring schools.

“The situation is either you have a great inclusive comprehensive sex ed program at your school or you don’t have anything,” she said.

“In my experience, most students have had very minimal sex ed before I have them as high schoolers. I can't think of a class that's more important going out into the real world, then sex education — 99.9 percent of the population is going to need this information at some point in their life.”

19-year-old Julissa Blancas said becoming a peer sex educator and Taga’s in-depth class helps kids talk openly and accurately.

“I learned more and so like I have knowledge where I can tell my mom, some of the knowledge you gave me was true — and false,” she exclaimed. “I’m open to talking about it with my mom but sometimes it can be really uncomfortable.”

Taga said when she asks kids why they don’t talk to their parents about sex, the No. 1 answer is fear of judgment. Just because they’re asking, parents assume kids are doing it, she said.

“A lot of times it’s the same curiosity that makes students ask why is the sky blue? Why do I float when I’m in the ocean? They're asking those questions out of curiosity. And that same curiosity is there with sex. They just want to know,” Taga said.

In the six-week class, students learn about anatomy, birth control, STI’s, period cycles and pregnancy. Taga recalled shortly after the class studied ovulation and menstruation, a girl texted her later that day: “Miss I think I just ovulated! She’s like, ‘I was putting on my jeans and I felt the pinch, the ovulatory pinch!’ ” laughed Taga. Students also learn about consent and relationship dynamics. Consent is important to prevent sexual assault, but Taga says class discussions are also about being a good person, a good communicator and a good sexual partner. Kaylene Claybaugh, 19, learned to not only hear consent verbalized but to watch for visual cues that someone is not ready and “look out for how the other person is feeling, where are they, how to communicate that.”

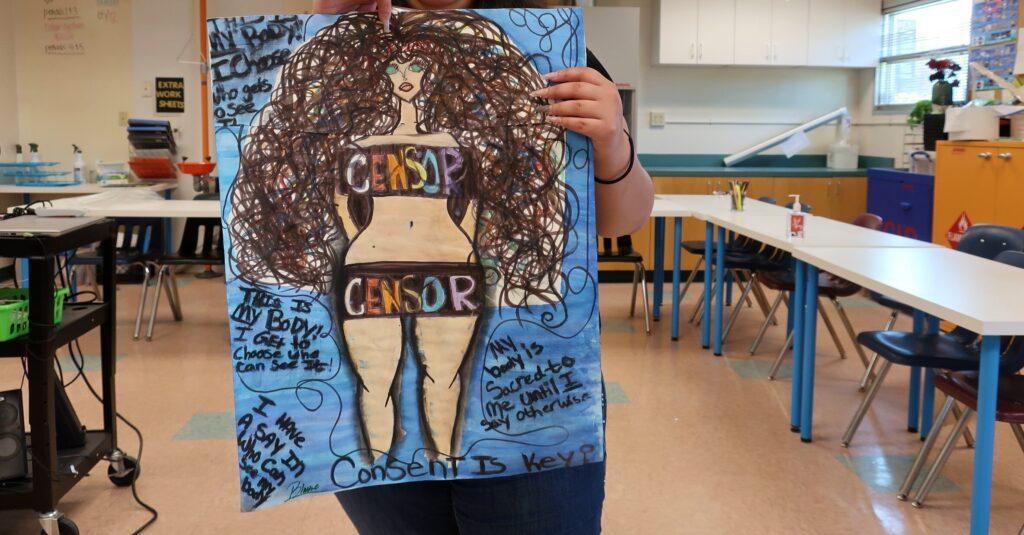

Some students focused their projects on their sexual assaults and the importance of consent.

One 17-year-old has two paintings. CPR doesn’t name sexual assault survivors. In the first painting, two bands reading “censor” cover the woman's breasts and genitals.

“You’ll see this one first, then you’ll have to ask consent to see this one,” she said, holding up her second painting of a woman lying in a garden, legs spread, with an “image” of an eye for a vagina. The woman’s hair is full and twisted blue and yellow and red with flowers in it.

“This is one my mom helped me with her hair and it’s just so gorgeous,” she said.

Another student who is a sexual assault survivor made a piece of digital art – red, orange, and black, showing a judge being influenced to make a ruling that she said didn’t serve her justice. The incident made her self-conscious about everything, insecure about herself.

She said she’s learned how to help other friends who have been sexually assaulted find resources.

“I feel like a lot of people go through sexual assault and none of them get the justice they need,” she said.

Other pieces by girls deal with their lack of self-worth and insecurities, making them fear intimacy. They say that women are much more than what’s on the outside.

Kaylene Claybaugh designed a red, orange, yellow and black graphic of part of a woman’s body, muscular and powerful.

“Women are so over sexualized for their bodies but there’s so much more in every woman. Yes, we can be sexy and fun, but there’s also power within women, and we don’t let them show it.”

Agneda Blancas said as her knowledge has grown through sex education classes, she learned self-acceptance. She drew a woman’s profile using bold black lines.

“My piece is a representation of the independent growth of myself as a young woman; as well as the growth of contentedness I have learned with my body, and the increase of knowledge on my body’s anatomy,” she wrote in her artist’s statement.

She said beyond anatomy, the sex education class taught her “personal stuff that I could take away if I ever get into a relationship.”

Twenty-one-year-old Saber Ali’s delicate piece is a purple background with two white outlines of faces, two people connecting with their souls.

“You can love whoever you want to,” said Ali. “Relationships aren’t just about physical attraction, they are also about the connection between two people’s souls.”

The peer educators said they’ve taught 12-year-old cousins about birth control, talked with friends about when to say “I love you,” how to come out to your parents, and consent.

One peer educator told Taga that before she took the sex education class, she would have told her 12-year-old cousin who was engaging in risky behavior that she was wrong, in a shame-based way. That wouldn’t have worked.

“But now after learning my sex ed course and the peer education training, she's like, ‘I came into it with no judgment and just gave her the facts, gave her the information that she needed. And then she was able to make a decision for herself that luckily, she agreed with, she was like, ‘oh good, now you get it,” said Taga.

Tori Cordova, 17, had the confidence to confront a boy when she saw him bothering and touching a girl in a school hallway.

“I was just like, ‘she said ‘no’ and I just hung out with her until he went away,” she said.

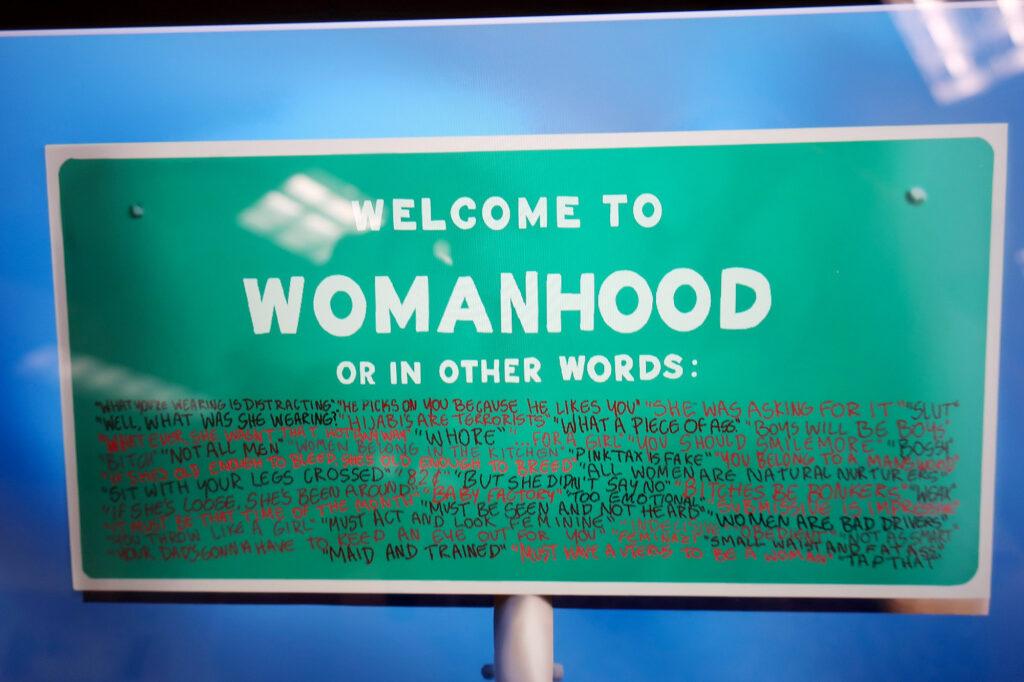

Cordova’s art project is a digital piece. It’s like a green “welcome to” sign for a state but it says instead, “Welcome to Womanhood’ with all the things – cat-calls, harassing language and more – that she, her best friend and mom have heard.

“Women belong in the kitchen, if she’s old enough to bleed, she’s old enough to breed, submissive is impressive,” she said. The list goes on.

“Whether it’s cat-calling or staring or actual assault, I’ve heard a lot of stories from peers but it’s very common, it’s horrible.”

In the larger culture, Cordova never sees women being empowered.

“Mexican women are very stereotyped as you’re just going to get knocked up right away. I’ve heard that so many times, told to my face, told to my friends' faces.”

So, it’s been important to her, to learn about contraception, to learn what it’s really like to have a child. The sex ed class and being more intentional about what social media she consumes she’s learned:

“You’re not those words, you’re not what other people say you are, you’re what you think you are,” Cordova said.

AUL Denver is hosting a Pleasure Artshop Gallery Walk of the students’ artwork on June 3, from 5–7 p.m.