If there's one thing Peter and Michelle Ruprecht don't miss about their old home, it's the chills and drafts that would leak in each winter.

The couple lived in Superior's Sagamore neighborhood, a middle-class subdivision near the Front Range foothills. The family could feel the winds pick up as gusts blew across drought-parched grasslands toward their home last December.

The family noticed smoke on the horizon before evacuation orders reached their phones. The Marshall fire would end up incinerating their home and more than 1,000 others across Boulder County, making it Colorado's most destructive wildfire and an event that reset expectations for climate-driven disasters.

In the months that followed, the Ruprechts resolved to rebuild and start over with a less-leaky home armored against future wildfires and poor air quality. The family’s research led them to Passive House standards, a set of design principles to seal homes in airtight, well-insulated bubbles. Combined with carefully placed windows, those techniques can reduce a home's energy needs by 90 percent compared to typical homes, according to the International Passive House Association.

But the Ruprechts soon discovered their ambitions faced a major obstacle: cost.

Record-high construction prices and low insurance payouts have squeezed Marshall fire victims trying to rebuild in Boulder County. The few local companies offering to build homes to Passive House design standards wouldn't work within the couple’s budget.

That all changed with a link posted in an online community group. It directed Peter Ruprecht to a web page for the RESTORE Passive House, a three-bedroom, three-bathroom home designed for the Marshall fire burn area. The designers promised a $550,000 price tag after government incentives, which fell in line with the construction quotes the family had received from other commercial builders.

The couple is now the first to sign up to build the home.

"It feels like a no-brainer," Ruprecht said. "We're getting better everything in terms of construction quality, fire resistance, comfort and doing a good job for the planet."

A well-sealed home for middle-class families

Debates over construction costs and climate-minded building standards have supercharged local politics in the aftermath of the Marshall fire.

Earlier this year, Louisville and Superior — the two communities hit hardest by the disaster — faced intense pressure from fire victims worried mandatory green building codes would further boost construction prices. Both local governments ended up allowing those families to rebuild to earlier, less-stringent standards.

The RESTORE Passive House attempts to prove green homes can fit within middle-class budgets. The task could prove critical as governments push to reduce the climate impact of buildings, which account for 13 percent of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions and 20 percent of Colorado emissions — largely due to natural gas appliances and an electricity grid dominated by fossil fuels. The homes could also help insulate families from climate threats like poor air quality and future fires.

Andrew Michler, the designer behind the new project, said the task requires a major shift in his industry. He said only about 20 homes in Colorado have met international Passive House standards and said designers need to start building for the mass market instead of focusing on one-off homes built for committed environmentalists.

"It's new for us. Designers are still getting used to building the standard, typical American home," Michler said.

Michler partnered with Seattle architect Rob Harrison and Joubert Homes, a local construction company, for the project.

The final design relies on simplicity to control costs. The exterior looks like two Monopoly homes placed in an L-shape centered around an independent two-car garage, ensuring space for storage and automobiles isn't included in the home’s heavily insulated shell. A pair of gabled roofs call back to Boulder County's architectural past as a mining community.

A suite of government incentives will bring costs down further. All-electric appliances qualify buyers for an additional $10,000 state incentive. Xcel Energy, Colorado's largest power company, has offered a $37,500 discount for fire victims who rebuild to Passive House standards. Smaller rebates are available for homes built with less-stringent green building standards.

Factoring in those discounts, Michler's team expects it can build one of the homes for $211 per square foot. Last February, the Colorado Association of Home Builders estimated the cost to rebuild standard homes in the Marshall fire burn area would range between $260 and $300 per square foot.

Christine Berg, a senior policy advisor for the Colorado Energy Office focused on local government, said the RESTORE project is only one of the green building plans enticing Boulder County families. Data from her office show that 95 households have filed permits to rebuild homes in the burn area. Of those, 39 owners have either registered with Xcel Energy for green building rebates or appear to qualify. She said three families have already registered to receive the largest discount available for homes built to Passive House standards.

"Out of this tragedy comes this great opportunity to really rethink how we build," Berg said.

A new building standard for a new climate

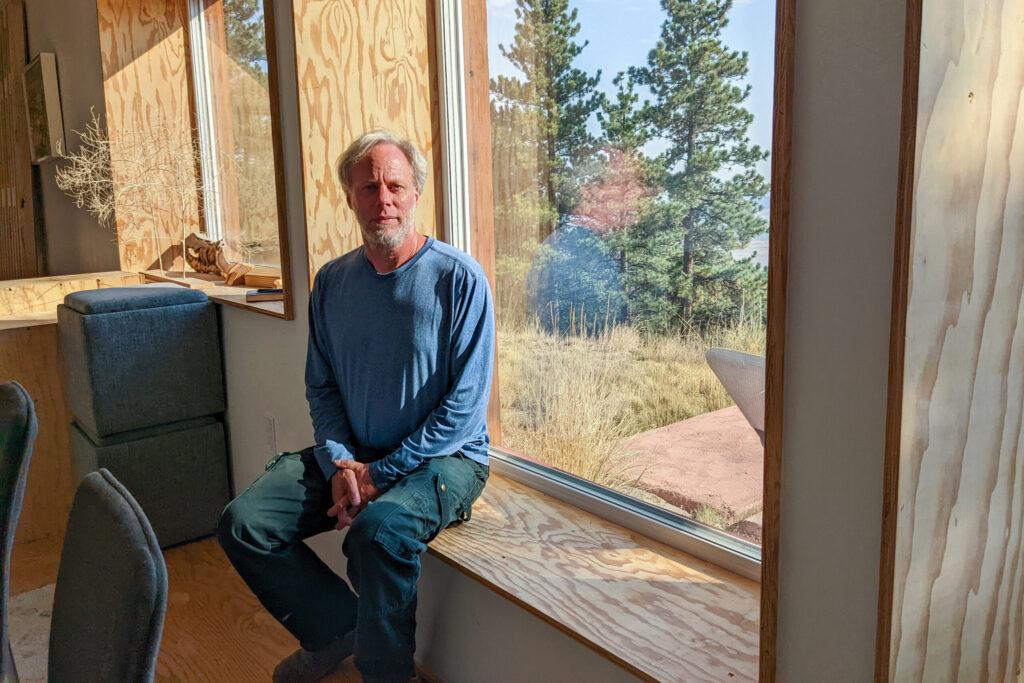

If all goes according to plan, the RESTORE Passive House should offer the benefits of Michler's own house in the mountains above Loveland.

The modern cottage is nestled beneath a peaked, metal roof. In 2016, it became the first Colorado home certified under international passive house standards.

A quick tour inside reveals an open-concept layout built atop plywood flooring. Deep benches in front of each triple-paned window benches show the walls are as thick as a car tire. Michler said the required heft adds an extra benefit in fire-prone areas: It rules out the possibility of any complex architecture that might trap wildfire embers.

Another advantage is indoor comfort, Michler said. Body heat and sunlight are often enough to heat the home in the winter. In the RESTORE Passive House, minimal energy needs should allow for far smaller heating and cooling appliances, allowing builders to recover some of the additional costs spent on extra insulation.

Out of all those advantages, it was the possibility of improved indoor air quality that sold Peter and Michelle Ruprecht on the project.

Passive House certification requires an airtight seal, which means builders include systems to filter outdoor air before it’s brought indoors. Ruprecht said the feature seems critical as climate change leads to more ozone pollution and wildfire smoke on the Front Range.

"People are going to want to snatch it up because they could be living in an environment with fresh air, all the time," she said.

To her frustration, the RESTORE Passive House has been slow to catch on among other Marshall fire victims, but interest is rising. Two other families have signed a letter of intent, Michler said. He’s received about a dozen serious inquiries.

Ruprecht hopes the team steps up its marketing efforts before families sign up with other builders. She’s excited to move into her own fire-resistant, climate-ready home — but would prefer to see similar models fill her neighborhood.

Editors note: This story has been updated to clarify references to Passive House design standards.