For the first time since the Great Recession, Colorado will fund public school students at the level voters called for when they passed an amendment to the Constitution more than two decades ago.

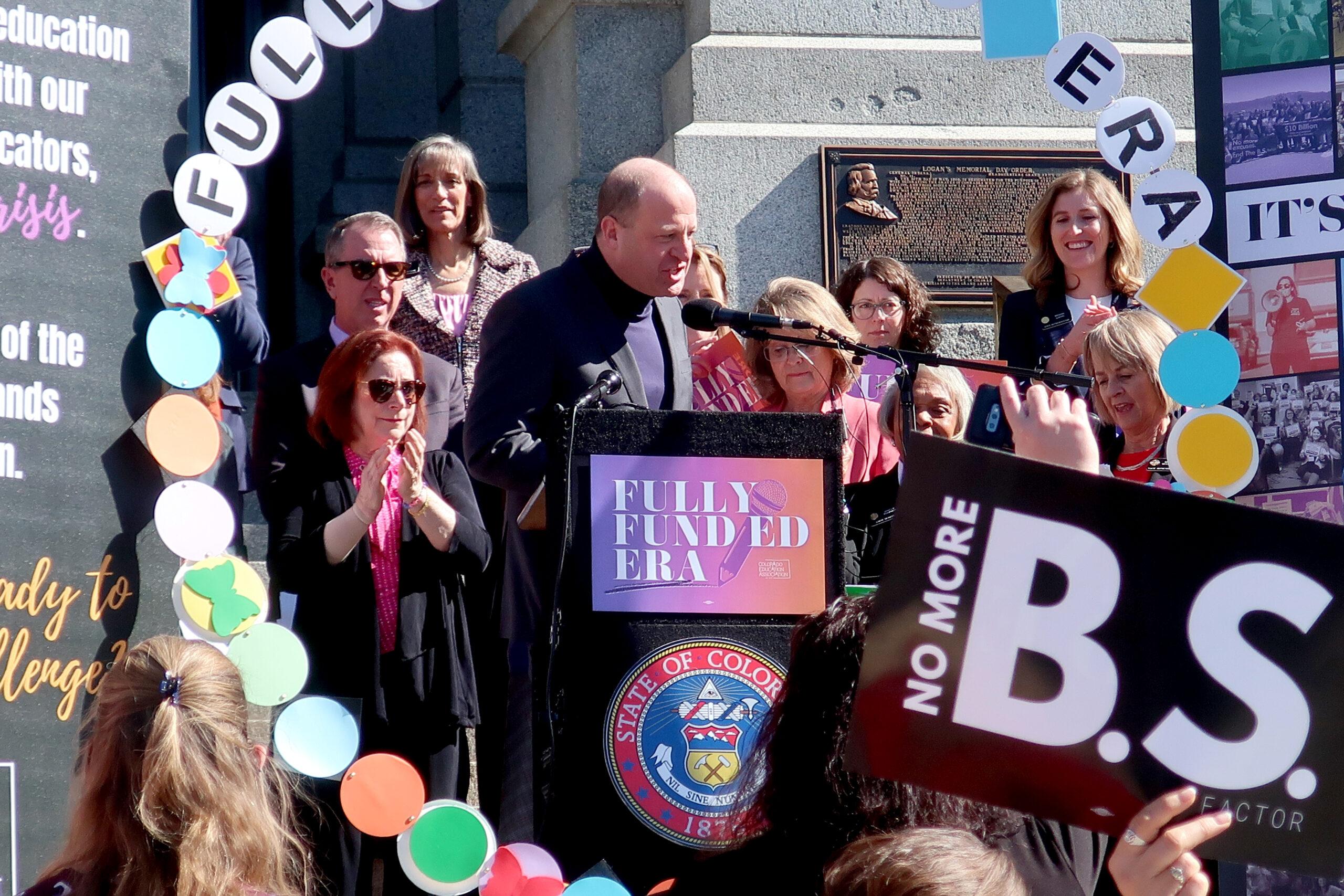

On Thursday, Feb. 29, Gov. Jared Polis, flanked by political and education leaders, celebrated the end of an annual multi-million-dollar shortfall lawmakers have imposed on public schools for a decade and a half.

“That means smaller class sizes,” he told a crowd of cheering educators on the Capitol’s west steps. “It means better pay for teachers. It means better pay for paraprofessionals. It means more opportunities and pathways for kids to succeed and get ahead to help power our state for the future. This is a big deal.”

Next year’s school budget will see per-pupil spending increase by $705, or about $15,000 a classroom.

“Let us not forget that this victory is not just about dollars and cents,” said Sarah Smith, who has taught preschool for the past 37 years. “It's about the profound impact it will have on the lives of our children.”

The joint budget committee on Feb. 23 included full funding for education, without the budget stabilization factor, also known as the BS factor, which allowed lawmakers to withhold money from schools. The bill to fully fund schools still needs to pass through the legislature. Lawmakers chipped away at the shortfall for years, but it wasn’t until the past few years that a good economy and a bipartisan push enabled zeroing out the final $140 million of yearly debt.

“There will be no more BS!” Republican Sen. Barbara Kirkmeyer told the crowd. “Education and putting our children first, that’s our top priority.”

Democratic Sen. Rachel Zenzinger told the crowd, that while the moment is a significant victory, there is much more to do. She said eliminating the BS factor brings Colorado to 1989 inflation-adjusted funding levels.

“Fully funding schools to 1989 levels should serve as the floor, not the ceiling,” she said.

Amie Baca-Oehlert, head of the Colorado Education Association, noted that her 15-year-old daughter will get the same amount of funding as Baca-Oehlert had when she was in high school even though modern schools must meet a dizzying number of new needs and demands.

During the era of the budget stabilization factor, an entire cohort of Colorado children who attended school between 2009 – 2024 have never experienced being educated in a fully funded school system.

Why?

Colorado voters decided 20 years ago to pass Amendment 23, which created mandatory funding requirements for public schools. But, when the recession hit, they weren’t mandatory anymore. State lawmakers created a mechanism – first called the “negative factor” and then the “budget stabilization factor”– that allowed lawmakers to withhold millions of dollars from public schools every year to balance the state budget.

For the past 14 years, schools have lost out on $10 billion that should have gone into classrooms. It meant years of program cuts, salary freezes, and numerous academic supports and instructional materials that children did not get. A school district like Denver had $1 billion fewer dollars to educate children. Jefferson County had $949 million, Aurora had $477 million, Pueblo had $200 million, and Douglas County had $719 million.

Worries about “BS factor II”

While school districts are elated by the elimination of the budget stabilization factor, they are worried about possible changes to the school finance formula this legislative session. House Speaker Julie McCluskie will propose changes to the formula that, if passed, would go into effect in the 2025-26 school year.

McCluskie promises she will consult with superintendents, parents, and education groups when her proposal is ready. But fears about what’s in it already have some districts preparing two budgets in the event of a worst-case scenario that one district leader said would result in hundreds of teacher layoffs.

“While I have been in public education for a very long time and absolutely know that our schools deserve more sustainable, ongoing funding from the state, it is just as important that we drive more equity into how we are distributing that funding,” McCluskie said in an interview.

She said students living in poverty, students learning English as a new language, or special education students require additional resources. McCluskie said she’d like a formula focused on student needs, not district characteristics. At the same time, she said rural schools don’t receive adequate funding given their small size and remoteness.

Why a new formula now?

The way the state funds schools hasn’t changed in 30 years. There have been multiple attempts, but no agreements. Voters have also rejected multiple plans.

There has been tension between making a more equitable formula and an adequate one. Some groups have argued for a formula prioritizing higher-needs students and small rural districts. But superintendents said that’s a noble goal but it can’t be done by taking money from one school district and giving it to another because of years of chronic underfunding.

In January, a bipartisan school finance task force released a report with recommendations for a new formula. It prioritizes higher-needs students, lower property wealth districts, and small rural districts. But the authors said that to make the new formula work, Colorado’s K-12 schools need another $474 million. The report said the recommendations should be taken as a whole and shouldn’t be implemented until a study examining what it actually costs to educate students is complete.

McCluskie doesn’t want to wait

She said she is confident the studies will show that Colorado is “woefully behind” in funding.

“I don't think that waiting for the results of those studies is responsible when it comes to equity,” she said. “My goal is to change a formula that right now I believe is inequitable.”

McCluskie doesn’t want to take money away from any child in the state but said the inequities require that more money go to schools with the highest need.

She said her approach would be “a very graduated runway to implementing a full change in the formula” and she would consider “a way that could ensure districts don’t go below the funding they’re currently receiving.” McCluskie said the current system has “winners and losers.” She did not provide further details on her proposal.

To ensure no district loses money at the same time funds are shifted towards students with higher needs, however, would take hundreds of millions of dollars that don’t appear to be there.

Bret Miles, executive director of the Colorado Association of School Executives, said the superintendents’ position is clear.

“We're not interested in a proposal that trades dollars from one school district to another school district,” he said. “We don't feel that there is any school district in Colorado that's overfunded.”