It’s not hard to figure out what inspires Steve Kaczmarek, who founded Borealis Fat Bikes in Colorado Springs 12 years ago. Just consider the names of a few of his bikes: Kaczmarek’s first bike was “The Yampa.” There’s “The Crestone,” and the electric bike is “The Keystone.”

“Everything we do has a Colorado theme,” said Kaczmarek. “All of our bikes have the Colorado flag on them. We just have great fun being from Colorado.”

Specialty bikes known as “fat bikes” took off right around the time Kaczmarek was starting the company. He describes their design, including larger tires, as ideal for off-road terrain and riding on snow, mud and loose gravel since they have a wider footprint and are more stable.

“You don't have to worry about going over whatever [terrain],” said Kaczmarek, as he pointed out some of the bikes at the company’s current headquarters. “Your eyes are up, you're enjoying, having a good time. They're just fun bikes.”

Kaczmarek has had some ups and downs since he founded the company in 2013, but he said the on-again-off-again tariffs on Chinese goods is a deal-breaker for the business. Borealis designs and assembles its bikes in Colorado Springs, but 80 percent of the parts come from China. Back in 2018, during Trump’s first term as president, Kaczmarek said the 25 percent tariffs Trump imposed and which President Joe Biden maintained cost the company $300,000.

The pandemic, on the other hand, was a boon for the outdoor industry business as people were able to take advantage of the extra time to recreate and started buying up more gear, including campers, outdoor gear and Kaczmarek’s fat bikes.

But when the pandemic ended, business slowed for the industry, something Kaczmarek describes as the “Corona hangover.” Kaczmarek had to let go of about half of his 12-person staff, so the company was still able to make a profit.

Then, in July of last year, Kaczmarek started planning for what he saw as the worst-case scenario: more tariffs that he figured could be as high as 50 percent.

“In July of last year, Trump was gaining speed in the polls, and I said, ‘I've got to move to a place where I have options,’” said Kaczmarek. “ I wanted a one-year lease, which was hard to find, and in the event things went bad, I needed to be able to either pivot or shut down.”

Kaczmarek moved from his 10,000-foot location to a 3,000-foot space and cut more staff, leaving him with three full-time and one part-time employees. Then came the election and the expected imposition of big tariffs on China. Kaczmarek decided he’d have to shut his doors this summer.

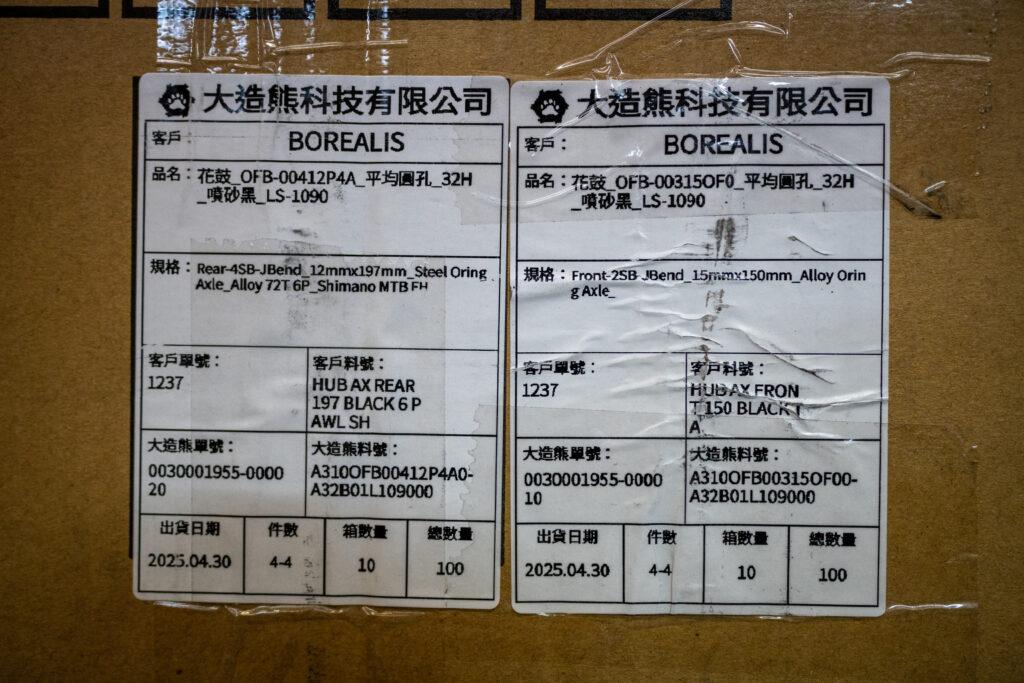

“We would've had to have placed orders in February because of the lead time from our suppliers, predominantly in China and then they go on the ocean for a month and then we get them and then we start building,” said Kaczmarek, noting it was just too risky to order more inventory without knowing how much it would cost.

It turned out the tariffs announced on China in April were much higher than Kaczmarek anticipated, so shutting down made sense. And Kaczmarek said even the recent pause in the trade war between the US and China won’t change his plans. There’s just too much uncertainty.

“We're down to our last 200 bikes. We're going to build those while I still have my staff,” Kaczmarek said. “We're exiting this facility at the end of July, and unfortunately, we're letting everybody go.”

Kaczmarek said he’s going to move any remaining inventory to his house and stay on the sidelines to see how the tariff negotiations play out in the long run.

Others in the industry said they may be forced to sit on the sidelines as well, like Matt Reichel of Boreas Campers in Pueblo, which makes campers built to go off-road and off-grid.

Reichel said the RV industry has declined significantly since its peak in COVID, and his company is running at 50 percent of what it was in 2022. He said the supply chain issues that started during the pandemic have never fully recovered and the company’s future is uncertain.

“It’s just whiplash for everyone,” he said.

He said the company, which also depends on parts from China, had been able to manage the 25 percent tariffs imposed in 2018, but 145 percent is a different ballgame.

Trump hopes that restricting American access to overseas products, especially from China, will incentivize manufacturers to start producing parts in the United States and create more jobs. But Reichel said even if tariffs were to stay at 145 percent, it will still be more expensive to buy his supplies in the U.S.

Borealis’ Steve Kaczmarek agrees. He said he doesn’t think anything he needs could be manufactured cost-competitively in the U.S. compared to China.

“I understand that we're trying to bring jobs back to the US,’ said Kaczmarek. “That's great. I fully support that, but not everything can be brought back.”

Kaczmarek doesn’t see the tires he depends on ever being made in the U.S. He said he looked into bike frames when he started the company and they were five times the cost of what they pay for bike frames in China. He said people just aren't going to spend what it would cost to buy a bike with US parts. One example is the carbon bikes he sells that run from $2,000-$3,000. He predicted a carbon bike with U.S. parts would cost about $10,000.

Kaczmarek said he worries how his employees will make ends meet. Dakota Mossbrook is one of the remaining three full-time workers. Kaczmarek calls him a superstar.

“We've got a really good group and it takes years to get a good group,” Kaczmarek said. But I can't keep paying them. There's just no way to do that.”

Mossbrook, who assembles the bikes, said he’d like to continue doing what he does, but the future doesn’t look good for the industry.

“What's happening to us is kind of happening to the entire industry,” he said. “So options are slim.”

Mossbrook is now looking for a job, but he said for him, the future looks bleak. And Kaczmarek will say goodbye to a business he created from the ground up.

Funding for public media is at stake. Stand up and support what you value today.