High school sweethearts Ted and Carrie Tahquechi have chased golden hours across the country. A sunrise over Boulder's Flatirons. A sunset on the coast of the Pacific Ocean.

They've shared a love for photography since they studied it together in the 1980s. In the decades since, they've undertaken multiple photographic projects, including landscape and portrait series, in color and black and white.

But in 1999, Carrie, Ted, and their 3-year-old twin boys were rear-ended in a car accident. Carrie got minor whiplash. The boys, Jarren and Jorden, were uninjured. But the impact shifted Ted's retinal tissue, permanently damaging his sight. Now, he has only 5 percent vision in his left eye. The other 95 percent of his sight is gone (though he's been blind in his right eye since college).

"Ted can still see some lights and shadows, some color, big things like bridges and mountains," Carrie explained.

But that's not a lot for a creative like Ted. So he and Carrie had to find a new way to make art together — and they landed on tactile photography.

Tactile photography allows people with low and no vision to experience photographs with their hands, feeling the contours like they would feel Braille. The images are also helpful for people with colorblindness and neurodivergent viewers.

But it was a long road from Ted and Carrie's accident to their new invention.

"It was a pretty dark time for us, for quite a long time."

As Ted adjusted to life with 5 percent vision, he had to adapt. But the process was long and tedious. As he learned new ways of navigating the world, he sustained frequent cuts to his face and forehead, concussions, broken bones, and had more than one close call with traffic.

But Ted's disability couldn't rob him of his love for art.

"When Ted lost his sight, we didn't stop going to museums. And we didn't stop going to art galleries," Carrie said. "I just had to describe all the things."

They also found places that provided special tours for the visually impaired. But Carrie said that didn't feel adequate.

"You know, in the back of your head, you think, 'Wouldn't it be nice if there was just one exhibit at each gallery that (someone with limited vision) could feel and experience without having to make a special appointment? Or without having to arrange for an audio-descriptive tour?’" she said. "Those (options) are fantastic, but what if Ted didn't have to make an appointment? What if he could just go in and see and feel and experience the art just like everyone else?"

A chance encounter

One day, Ted and Carrie were at Access Gallery in Denver's Santa Fe Arts District. As they were standing in front of the work, Carrie began to describe — in great detail — what they were seeing.

"And one of the most amazing things happened," Carrie said. "The curator (Damon McLeese) came up to us, and he listened. And then he turned to us, and he said, 'I have never heard anyone come in here and audio describe what was going on like this. We need this.'"

For Ted and Carrie, that was a turning point.

"We know that there's a need out there," Carrie said. "And curators know that there's a need out there."

So she and Ted set out to meet that need by making art more accessible.

Creating photographs that can be seen and felt

Carrie and Ted tested a variety of mediums, from layering paint and glue to sculpting with paper.

They were all a bust.

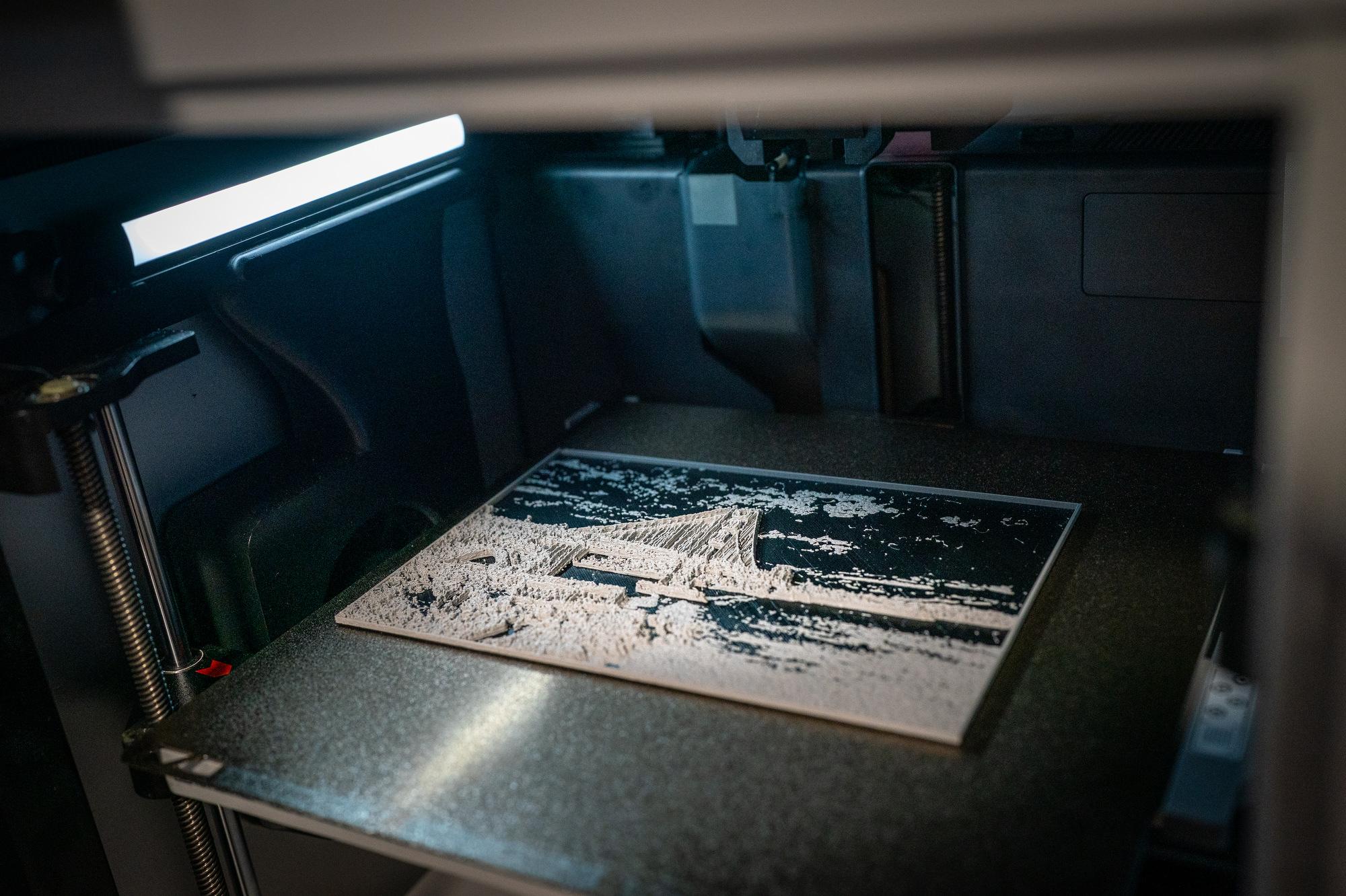

Then, they discovered 3-D printing. But that also had its challenges.

"It was a pretty long process trying to figure out how to make something without any texture to it print with texture," Carrie said. "A lot of (the test prints) were comically outrageous. Just a big pile of swirly mess."

"Yep," Ted said. "It's called spaghetti."

A hot room, a cold room, or a dirty printing surface can all affect the success of a 3-D print.

Plus, it's hard to teach a 3-D machine how to print light and shadow in a way that makes sense to the human hand.

"When you first throw a picture through the 3D printer, it comes out with the tactile equivalent of static," Ted said. "So you're not feeling all the things that you need to feel to experience the composition of the image."

But together, after much trial and error, Ted and Carrie honed their technique.

"We found a process where we can extract different layers of texture, form, light — a bunch of different things in a photo so that you can experience a mountain, a bridge, a sunset."

The images are displayed with a visual print, a 3-D print, a written description, a Braille description, and a QR code that links to an audio description.

"It tells you the mood, the time of day … it gives you the description of the photo, and then it walks you through what you're feeling in the tactile version so that you have full context of what it is that you're experiencing," Ted explained.

A future where all galleries, museums, and exhibitions are accessible

To further their work, Ted and Carrie secured funding through a RedLine Colorado Artist Grant, sponsored by the Andy Warhol Foundation. The money allowed them to purchase a 3-D printer, so they don't have to schlep back and forth to a library or makers' space every time they want to print.

They also received a travel grant from Flight for Sight (now the Blind Travel Foundation), which allowed them to capture iconic landscapes and vistas across the country.

"Big pie in the sky dream," Carrie said, "would be that someone with low vision or no vision could walk into any gallery and experience art by touch without making an appointment or having a special showing."

But that's a long way off. For now, Carrie said, step one is setting up a 501(c)(3) for their business, Tactile Photos.

"That's our current project, so we can subsidize the printing and be able to offer these, for free, to different museums and studios and things like that here in Colorado," she said.

Imagine seeing something for the first time

A few months ago, at a National Federation for the Blind conference in Florida, Ted and Carrie were reminded of the impact of their work.

At the conference, they met a blind woman who grew up in Boulder. Unlike Ted, she was never sighted.

One of the many landscapes in Ted and Carrie's collection is an image of Boulder's Flatirons at sunrise, with a grassy field in the foreground and a clear sky in the background.

So they invited the woman to feel the image.

"She never really understood why people talked about them all the time — because when you never have sight, you don't really understand how enormous the mountains are and how they look different when you're really close up to them, or if you're far away from them," Carrie said. "It's a very emotional thing when people feel these for the first time."

"It seems like every single time we show this work, there's just so much emotional outpouring," Ted added. "For me, it feels fantastic to be able to share that."