When your nickname is "The Queen of Pain," you probably have some good stories.

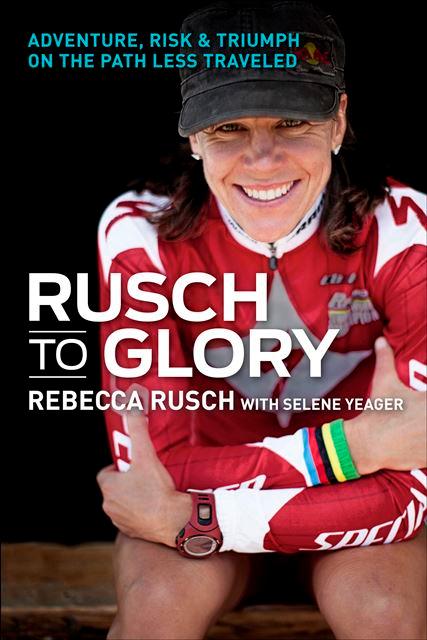

Rebecca Rusch, who's won Colorado's Leadville 100 mountain bike race four times, proves that's true in her new memoir, "Rusch to Glory." Fellow cyclist Selene Yeager co-wrote the book.

In an interview with Colorado Matters guest host Sadie Babits, Rusch said she got the nickname from her peers during her adventure survival racing days, which preceded her career in mountain biking. Rusch competed on multi-day races all around the world, including "Eco-Challenge," which aired on television from 1995 to 2002.

In the book she describes the pain she endured in those races, during which she quickly transitioned between trekking, rock climbing, biking, and swimming -- and slept just an hour or two a night on average.

No matter how well trained you are, the body and mind begin breaking down. The mental fatigue means more navigational errors. Because you cannot keep up with your calorie expenditure or recover from exhaustion, your body is in a state of deterioration, literally cannibalizing itself to survive...

From here until the finish line, you must tap your mental reserves to take over where the physical cannot. Every cell in your body is screaming at you to stop moving, and your mind must override those signals as you stumble on.

Rusch enjoyed traveling the world in a way tourists aren't able to, she said. And she enjoyed pushing her limits.

"When you strip away the physical comforts of a warm bed and a hot meal... I really found out what I was made of," she said. "And so, the suffering does go along with it, but the result in the end is this huge reward that I don't think I could get from just going on a 30 minute run around my house."

After Eco-Challenge ended, Rusch said, the sport started to decline in popularity. That combined with a fatal accident she witnessed during a race in 2004 led to Rusch's decision to find a new career.

Enter mountain biking. Rusch said she struggled with the technical aspects of cycling, but that didn't stop her from winning the first few races she competed in. She did it partly by carrying the bike, she says, over difficult sections.

Competing in Leadville is truly unique, Rusch said.

"It's one of the few places where pros, joe schmoes, first-time racers, elite racers, we're all on the same race course. We're doing the same thing," she said.

"And because it's out-and-back, you actually look in the eyes of all these people who are still heading out even if you're winning the race," she added. "It's the one place where it's really gathered in one big group of people."

Now in her mid-40s, Rusch says she will continue racing in the Leadville 100, and is looking for new adventures, like multi-day bike treks around the world.

Rusch originally got into sports in high school, when she went out for the cross country running team. Back then, she wasn't driven by a desire to compete. Instead, she struggled with body image issues.

"As a young girl going into high school, I didn't want to be overweight. And our neighbor who was on the cross country team basically just said, you know, 'Oh, if you're worried about body image join the cross country team. You'll never get fat and you get a free sweat suit,'" Rusch said.

While she joined the team with that motivation, though, the team introduced Rusch to some of her best friends, and sparked an interest in the benefits of hard work and teamwork.

"It really changed the trajectory of my life," she said.

Rusch has some advice for athletes who want to push themselves further in daily workouts. First, pick the right sport and sign up to compete.

"You have to have something that makes your hands sweat a little," she said. "If it doesn't elicit a little bit of excitement or adrenaline, then maybe it's not the right goal for you."

She said friends are excellent at motivating her.

"Sometimes I can't get my own butt out the door, and I need my friends to be like, 'Okay, we're meeting at noon.'"

Rusch has made a career pushing herself to her physical limits, but she does still experience pain -- and fear.

"Probably the biggest fear I had was launching this book," she said. "Putting myself out there in this way was terrifying, and it felt really strange. Looking back now, in the rearview mirror, I'm super glad I did it and the reception has been really positive, and so I'm glad that I conquered that fear."

Read an excerpt

Reprinted from Chapter 12 of "Rusch to Glory" with permission of VeloPress. Copyright (c) Rebecca Rusch and Selene Yeager, 2014. As you squeeze into the starting corral and find your place among more than 1,500 wide-eyed, shivering cyclists at the corner of Sixth and Harrison streets in downtown Leadville, Colorado, you are effectively standing on the rooftop of the nation. At 10,152 feet, it’s the highest incorporated city in the United States. The often snowcapped mountains you are nervously eyeing require more than 11,000 feet of climbing by day’s end, including a trip up to the infamous Columbine Mine, which almost takes your breath away at 12,424 feet. Rich in silver and other precious metals, Leadville was a boomtown in the late 1800s and early 1900s, when prospectors poured in by the tens of thousands. It suffered the same fate as other mining towns, however, with several periods of boom and bust before almost all of the mines shuttered, including the largest in 1983, leaving half the townspeople suddenly unemployed. The displaced moved on in search of greener pastures—all except former miner and marathoner Ken Chlouber. The year the mine closed—about the time I laced up my first pair of running shoes as a high school freshman on the Downers Grove North track team—Chlouber hatched a plan to put Leadville back on the map and revive his struggling community. He would create a 100- mile ultrarunning event that would push competitors to their limit as they tackled the big mountains at high altitude. Legend has it that when he told the local hospital administrator about his idea, the man responded, “You’re crazy! You’ll kill someone!” Ken’s reply: “Well, then we’ll be famous, won’t we?” He was right . . . about the putting Leadville on the map part, anyway. The running race became wildly popular. So popular that they added five more events to make it a series. Then, in 1994, they added the Leadville Trail 100 MTB race, now just reverently called “Leadville.” It parallels the running course, sharing a few sections in common. The course is generally referred to as a 50-mile out-and-back, but it actually runs over 103 miles; the difference between 100 and 103 miles looks miniscule on paper, but when you’re pedaling those final 3 very challenging miles back through town and up the section affectionately known as “The Boulevard,” they seem like an eternity. Back in 1994, when the race first started, mountain biking, let alone Leadville, wasn’t even on my radar, but the race quickly became the ultimate endurance challenge for mountain bikers who want to test their mettle. Finishers who cross the line within the event’s 12-hour time limit get a shiny silver belt buckle. Those who break the 9-hour mark are awarded the “La Plata Grande,” a gigantic gold-and-silver belt buckle that is so large, it’s actually hard to wear. Outside of the cycling community, it looks a little funny and draws odd glances. But among the endurance cycling crowd, it is worn with extreme pride as a badge of honor. Lots of riders really want those buckles. LEADVILLE’S SIXTH STREET is the Champs-Élysées of mountain biking. It’s the closest thing we mountain bikers have to the magnitude of celebratory mayhem that Tour de France racers bask in as they roll through the streets of Paris on the final day of the grand tour. And like the Tour de France, there are racers who plan their entire season around that singular event. In 2010, I joined the crazed masses and put all of my attention toward Leadville too. After the Lance-driven documentary Race Across the Sky, Leadville—already on many mountain bikers’ bucket list—became a must-do for serious endurance cyclists and was easily the biggest, most well-known mountain bike race on the planet. Adding to the growing hype, Chlouber sold the race series to the then title sponsor, Life Time Fitness, a Minnesota-based company that operates more than 100 fitness, family recreation, and spa centers across the United States. With a corporate powerhouse to back it, Leadville was poised to gain unprecedented exposure. On the practical side, for a professional athlete like me that meant an opportunity to be seen by many more potential sponsors. It also meant stiffer competition, since more athletes followed the same train of thought and showed up to take a shot at grabbing a piece of the pie. Because the 2010 Leadville would be my A race for the year, I approached it differently. Matthew made significant adjustments to my training to allow me to race fast for eight hours instead of the more metered-out 24 that I was used to. I realize that for most people eight hours sounds like a long race, but for me it is short, fast, and furious. I had to work on speed, learn how to go harder, and enter into a different realm of pain—short-lived and sharp. In preparation I packed in four multiday stage races, Trans Andes Challenge, Tour de la Patagonia, Red Centre MTB Enduro in Australia, and Trans-Sylvania Epic, even before summer rolled around. I even raced short cross-country races. Then I pulled the equivalent of a fitness cram session by stacking multiple 50- and 100-milers in the six weeks leading up to Leadville. It was an aggressive, ambitious schedule. Matthew worked me hard with extended sessions of elevated fatigue, and there were many bleak moments when I struggled to keep my confidence and sanity. Effective training must strip an athlete down almost to the breaking point, then pull back in order to build them back up. It’s a process that feels really demoralizing when you’re in the middle of it and can’t see the light at the end of the tunnel. I was about to succumb to the strain and pressure right before Leadville and I called Matthew in the middle of a meltdown. The conversation pretty much went like this: “I suck. What is wrong with me? I feel fat and slow and awful. I should consider a career change.” His enthusiastic reply: “Excellent. We’re right on track.” I was freaking out, but there was nothing I could do at that point but go with what I had and hope that he was right, that I actually had the talent and fitness it would take to win and that his training regime had been effective for me. All that was left to do now was rest, wait, and absorb the training. Unlike 2009, when I basically stopped, dropped, and rolled to the start line with barely a clue about which way I was going, in 2010 I committed to being in Leadville 10 days early so I could ride the course and acclimatize properly. I was there alone in town, riding and simply hanging out, breathing the thin air. Without the distractions of home, TV, and other work, I had plenty of time to think about the race, my nutrition, my bike setup, what to wear, the weather, and all the myriad variables that go into Leadville. Some days, frankly, there was too much time to think, and I’d nearly make myself crazy with minutia. But mostly it was a rare respite from my normally chaotic work, training, and travel schedule. By the time the big red Specialized truck rolled into town, I was like a racehorse kicking in the stall. Specialized had jumped on as the official bike sponsor of the race. Company owner Mike Sinyard was back to better his time on the course. Also on the team roster was newly crowned cross-country and short track national champion Todd Wells, and mountain bike legend Ned Overend, as well as a host of other Specialized employees and dealers. It was really great to see so many Specialized uniforms on the course. We were all part of the Leadville family, and now I had some of my Specialized family there with me too. Greg was my official crew for feeds, time splits, and moral support. He was an efficient one-man show and all that I needed out there. He’d brought his motorcycle and had scoped the aid stations, and we made a plan where we would meet on course. We even practiced with musette bags—cloth bags with a long handle that you can grab and sling across your shoulder, making it easy to dig out your nutrition on the fly. I had never used this tactic before, but after watching Race Across the Sky, I could see that the top guys were saving precious moments by keeping the feeds fast and rolling. I had also seen videos of riders getting tangled in their musette bags and crashing. Grabbing a swinging musette filled with water bottles at race pace required practice. I know I was being laughed at the day before the race as I rolled up and down the street practicing the handoff with Greg. Although I tried to find as many little tricks as possible to shave time, I also needed to rely on what I knew, and that was pacing. I was armed with support this time around, but my competition would be gunning for me. In particular, Amanda Carey had targeted this race as well, unsatisfied with her race the previous year and back with a vengeance. With new sponsor expectations, media interviews, and a target on my back, it was just about impossible not to get caught up in the hype. The exposure is a form of flattery and job security but also a distraction that can be overwhelming. I set my mind to focus on racing my race and the things I had control of instead of reacting to the other athletes. After the gun went off, we were soon climbing the first hill up to St. Kevin’s. Amanda stuck to me like glue. I tried to shake her a few times going up that hill with no success. It was the two of us and about five guys pushing together in a group until the next big climb at Hagerman Pass. At that point, I surged again, and one by one, Amanda and I dropped the guys. I did not want to pull her around the course, so I was trying to get away early, if possible. I created a small gap, but she clawed right back up before the descent down Powerline. I wanted a clear path on the dangerous descent, so I surged again to keep her from coming around. She didn’t pass me before the descent, but I also didn’t shake her. “I’m relieved that’s over,” I told her after we got down safely. Back to business. We played cat and mouse, chasing and pursuing, each of us looking for a chink in the other’s armor, through the Pipeline aid station and all the way to the Twin Lakes aid station. On the bike, I ate, drank, tried not to panic, and mentally prepared myself for the 3,200- foot Columbine ascent. At Mile 40, Amanda and I were still together, pushing each other to what was sure to be a record-breaking time. I didn’t know our pace or our splits. I was 100 percent focused on our two-person race and nothing else. In many ways Leadville is a mountain bike race with road racing tactics mixed in. This year, I was experiencing that firsthand by sitting in a group of riders for the first 40 miles and grabbing musette feeds through the aid stations. I found myself really enjoying the strategy and tactics. I was ready to hit the big climb hard to see if I could open a gap there. Greg and I had done a lightning-fast rolling feed, and I was able to pass Amanda while she was stopped with her crew. I punched hard at the bottom of Columbine and did not look back. Okay, I’m lying. I probably looked back within two minutes of heading uphill, but I couldn’t see her through the tree-lined switchbacks. I set my eyes forward and kept pushing, focusing on maintaining an efficient spin with my legs, just like I’d practiced on that hateful indoor bike all winter long. I felt if I could stay out of sight during this forested section, perhaps she’d let her guard down just a little bit. For 5 miles, the Columbine climb is thickly treed with many 180-degree turns and straightaways stacked up like a layer cake. As I made each turn, I would sneak a glance behind me. No one was catching me, and now I started passing some of the faster guys and moving up farther in the field. This felt like the decisive point of the race, so I decided to treat it as a time trial and just go for it. If I blew up on the climb, perhaps I would still have time to recover on the descent. If I didn’t blow up on the climb, I might be able to gain an insurmountable lead. My plan was working until I reached tree line. I started to cramp at the steepest part of Columbine, just as the crest was within reach. The air was thin and the terrain was so steep that I could barely keep the pedals turning over. I stayed on my bike, trying to force down electrolytes and fluids without falling over. I wanted to keep pushing hard to make it to the top so I could rest on the huge descent, but I remembered that the top of the climb was also just the halfway point of the race. I was walking that line between pushing myself to the limit and pushing myself too far past the point of no return. I knew it was risky. I was either headed for an awesome finish or a spectacular failure. At the turnaround on the top of the world, I looked at my watch for the first time. I was eight minutes ahead of a record-breaking pace. I had to look a second time to be sure I was seeing clearly and not hallucinating. In an instant, the numbers flew out of my brain and I got back to work. I began the descent and darted my eyes from the loose surface underneath me to the uphill traffic next to me. I spotted Amanda and calculated that I’d put about five or six minutes into her on the climb. That worked out to be a gain of about 45 seconds per mile. It was really good given the short distance, but the gap between us was much smaller than the previous year. I set that thought aside and returned my focus to the descent. Between the thousands of oxygen-deficient riders teetering as they pushed up the hill and the fatigue settling deep into my muscles, the descent was treacherous and far from relaxing. As I came into the Twin Lakes aid station, I saw Greg there, waiting in our usual spot, and I caught the excitement in his eyes. I had finally shaken Amanda. And I had opened a 10-minute lead. His demeanor is always calming for me. He’s never frantic. As I grabbed my musette bag he said, “Just do what you do best.” In that fleeting moment, it was precisely what I needed to hear. I would not settle for a 10-minute gap. I wanted this, and the fierce competitor in me was prepared to work harder than ever. The risk I took on Columbine had been worth it so far and it was time to protect the lead I’d gained. Leaving Twin Lakes, you’re abruptly greeted with silence and solitude, save for another rider here and there, for the 40 miles back to town. After the mass start with thousands of fans and riders, the pack riding to Columbine, the throng of humanity riding uphill as you’re bombing downhill, and the deafening din of the spectators at Twin Lakes, the contrast is enough to make you feel almost lonely. But for me, being in my own world, just riding as fast as I can without distractions is the type of riding I find most familiar. However that section of the race delivers another challenge: It’s the windiest part of the course. Naturally, today there was a headwind. I could pick out a rider in the distance. I set him as my target and crouched as low as I could on my bike for aerodynamics. I had to push harder than I wanted to for about 20 minutes to finally catch him—another strategic individual time trial. Once I caught him, we rode together for about 20 minutes. I desperately needed some shelter from the wind, which he provided. And while few words were exchanged, having another human being to suffer with was somewhat comforting too. The reprieve didn’t last long. As I hit the back side of Powerline at Mile 80, I plummeted deep into the pain cave. I had been flirting with cramps since Columbine and was digging really, really deep, just as the Leadville tagline tells us to do. Powerline is wickedly steep at the bottom, and as I tried to put power into the pedals I felt the cramps coming again. I didn’t want to end up seizing and writhing on the side of the trail, so I set my ego aside and put my adventure racing skills to work. I walked up Powerline, but I walked intentionally and took long strides in order to keep a decent pace and stretch out my legs. Fans yelled for me to get back on my bike. In my mind, I was thinking, You try riding this hill, but mostly I was too numb to waste the breath. My ultimate goal was the finish line, not this 1-mile section of the course. And my strategy was working. My cramps stayed at bay, and I was able to push fluids down as I walked. Once at the top, I snuck a look down the hill, but I couldn’t make out the riders at the base. I swung my leg back over the bike, took a big mouthful of air and readied myself for the homestretch. I couldn’t for the life of me figure out how much time I had left in the race or if I was going to break the course record at my current pace. I finally gave up on the math and fixated on the burdensome task of turning the pedals over faster and faster. Don’t let up, even for a second. No coasting; pedal harder. This was my mantra. I was alone at the top of the last big climb. I couldn’t see anyone in front of me or behind me. Where were all those people who started the race? I was utterly depleted and running on fumes. I needed water badly. Thankfully, Carter Summit neutral aid station was coming up. I wouldn’t see Greg here, but I knew they had some supplies and I was desperate. I had to unclip and step off my bike to fill my bottle, and as soon as I put my foot on the ground, my calf muscle fully seized and I fell over in the dirt with my bike on top of me. The aid station volunteers stared at me in disbelief as I frantically rubbed my cramp away and untangled myself from my bike. Between gasps for air, I begged for electrolytes. I was panicked that the calf cramp could turn into a full leg cramp and prevent me from pedaling the 10 miles home. The eager volunteers shuffled through their supplies and proudly offered me a saltshaker. Not exactly what I was looking for, but it couldn’t hurt. I cocked my head back and took a few big shakes straight into my mouth. I swished the salt around with some water, swallowed, and headed off. I probably should have tossed a bit over my shoulder for good luck too. The final descent down St. Kevin’s is the last really high-consequence obstacle on the course. This is the place where many bone-weary riders get complacent and end up flatting or crashing on the rocky trail. It felt great to stop pedaling for a bit, but all of your energy is spent hopping rocks, navigating ruts, and willing yourself not to touch the brakes. In Race Across the Sky Lance Armstrong flatted at the base of this descent. Whether it was lack of skill or lack of tools, he was unable to change the tire himself and was forced to ride the final few miles to the finish on his rim with an eye over his shoulder. When I finished this stretch with my tires still inflated and firm, I let out a celebratory shout into the woods. All that remained was the mind-numbing Boulevard section back into town. I stole another backward glance before turning onto the final grinder hill. No one in sight. I was so close, yet it felt so far away. The film crew moto was with me at this point, but I couldn’t manage a smile, comment, or even a glance at the camera. Head down, I was slumped over my handlebars, staring at the ground. My top tube was covered in snot. I was breathing like a horse and pedaling squares— every single stroke hurt like hell. It wasn’t pretty, but I wanted to beat that long-standing women’s course record. I stared at my odometer and kept glancing at my watch to check the race time. I knew it was within reach, if only this stupid Boulevard would end. As I crested the very last hill and finally turned onto the smooth pavement of Sixth Street, a group of girls started running next to me screaming and yelling, “It’s the first female!” It was a local Colorado high school cross-country team, and they were going crazy for me. I wanted to say something back, but the words wouldn’t come. I did, however, muster up a smile as my heart filled with joy. I thought about my high school running team and my introduction to sports so many years before. I hope they realized how their energy and enthusiasm pushed me over that last hill. I could finally see it, Sixth and Harrison, with the red carpet and the finish banner. But it stretched out before me like the ever-expanding hallway in The Shining. Was I hallucinating? Was it really getting farther away? The film guy on the motorcycle must have sensed my struggle and noticed my lethargic cadence because he said, “Come on, Rebecca, only six more blocks.” His words broke my trance. I put my head down, shifted into a bigger gear, and went. I had ridden this finishing stretch multiple times visualizing this moment. I could feel the crowd and the time ticking in my head. At last the red carpet was under my tires and the clock finally stopped. I had the win and the record, but I was so depleted I could not even raise my arms in victory. Crossing the line at 7:47:35, I took first in the women’s field and 22nd overall. I’d improved my time from the previous year by 27 minutes, with an average speed of 12.8 mph. I broke Laurie Brandt’s course record, which had stood for 10 years, by 11 minutes. I was 1 hour and 30 minutes behind Levi Leipheimer’s record-breaking men’s time. It was one of the best races of my life. Greg was the first to approach me and give me a hug as I slumped over my handlebars, too fatigued to fully process it all, yet soaking in the relief and joy of those precious moments right after a hard effort. I attribute the record and the win to great preparation, a little bit of luck, and a whole lot of suffering. In my first attempt at Leadville I went as hard as I could have, but I didn’t know the course and my training in the run-up to the race was focused on the 24-hour format. I felt like my focused cycling training was now actually making a difference, and it came together for me on the right day. But all the preparation in the world doesn’t take into account the preparation other athletes do, the mechanical problems that can happen, the crashes, the wind, the getting sick, and everything else that can send a race sideways. It was the most painful day I’ve ever had on a bike . . . but also one of the most rewarding. I’VE NEVER BEEN ONE to rest on my laurels. As a pro athlete, I wouldn’t have that luxury anyway. But I do like to have a day or two to appreciate an achievement and kick back after a season of arduous, all-encompassing training. There is no such luck in professional sports. It’s a culture steeped in demands that all ask essentially the same thing: “What’s next?” Moments after I crossed over the red carpet in 2010, I was already getting peppered with questions about my 2011 schedule and whether I would be back to defend my title and attempt the first-ever woman’s three-peat in Leadville. A friend even prodded me to keep coming back and winning so I could become “the female version of Dave Wiens.” Dumbfounded, I responded with a question of my own, “Can’t I just enjoy this win for a little while before having to focus on 2011?” The answer, loud and clear, was a big, fat no. In fact, I still had some big plans to see through in the next month, much less the next year. As a professional athlete, much of your security is pinned to the podium spots you currently have and your potential to garner more in the future. Sponsors like winners, and you are only as good as your most recent result. Performing well over and over and over again is what’s expected and rewarded. After just five years of bike racing, I had four national championships, three 24-hour world championships, and back-to-back wins and a course record at Leadville, but my bike sponsor didn’t recognize me as a true world champion because I hadn’t won a UCI-sanctioned race. At Matthew’s suggestion, I decided to go after a bona fide UCI world championship—the 2010 UCI Mountain Bike Masters World Championships in Brazil—and fill that hole on my resume once and for all. The Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI) is the world governing body for the sport of cycling. It issues cycling licenses, sanctions races, and oversees world championships. When you win a UCI-sanctioned world championship, you get a specially issued team uniform with the coveted UCI rainbow stripes on it, designating you as a world champ. These simple, colorful stripes are known worldwide, and once you earn them, you have the right to wear them on your sleeve for the rest of your life. They can never be taken away. Though the competition was fierce at the 24-hour solo worlds, those events were never sanctioned or officially recognized by the UCI. If I wanted to wear those stripes, I was going to have to step out of my comfort zone and do an exponentially shorter world championship event. Given the rules of physiology, my training regime would have to undergo some big changes in a short amount of time. |