Let’s go back to 1889, when art opened viewers to new worlds before moving pictures were even really a thing. That’s when Frederic Remington painted “A Dash for the Timber,” now considered one of his masterpieces. Back then, this chaotic scene was a departure in western American art.

When it first went on display at the National Academy of Design, surrounding works depicted bucolic landscapes and quiet scenes of the West, says Denver Art Museum curator Thomas Brent Smith.

“Then here’s Remington with this painting that is so brazen, so full of action,” he says. “He realized that he could get audience’s attention using action.”

It’s nothing new to see works by Remington, Albert Bierstadt and Charles Marion Russell at a museum with an entire department devoted to western American art. In a very Hollywood-esque move, there needed to be a twist. So when the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts reached out to the Denver Art Museum about putting together a show on the West, the institutions decided to try something different. The discussions kept coming back to movies.

“Film has such an impact on how we understand or misunderstand the West,” Smith says. “It has had the most impact, reached the most people of any of the visuals.”

The exhibition, which bears the title of “The Western,” traces the leap that these iconic characters, scenes and landscapes took from painted canvas to the silver screen. Next to Remington’s painting of cowboys on horseback, you’ll see a mad dash come to life in clips from six different movies like “The Wild Bunch” and “Tombstone.” This juxtaposition offers a glimpse of Remington’s influence, Smith says.

John Ford, the prolific film director behind “How The West Was Won” and “Fort Apache,” spoke openly about drawing inspiration from Remington for his popular westerns. In a gallery dedicated to Ford, his 1939 film “Stagecoach” plays beside Remington’s 1907 painting “Downing The Nigh Leader,” which depicts a stage coach frantically outrunning a group of American Indians.

“You see Ford not just taking the aesthetic, but in this case he also projects the narrative forward,” Smith says.

And yes, you can also count on seeing Hollywood cowboy John Wayne, who starred in many of Ford’s films. The exhibition dives deeper into representations of the cowboy and American Indians. Paintings, sculptures, books and movies track the evolution of these two iconic old west motifs.

“I think there’s something about a Western story, often times it doesn’t focus on individual’s stories, but rather the sort of shorthand character types,” Smith says.

The show also highlights Italian director Sergio Leone, popular for his spaghetti westerns like “The Good, The Bad and The Ugly.” From there it takes some unexpected turns, like western art’s influence on the counterculture era, which gave us films like 1969’s “Easy Rider.” It all culminates with a selection of contemporary works by artists like Gail Tremblay and Fritz Scholder.

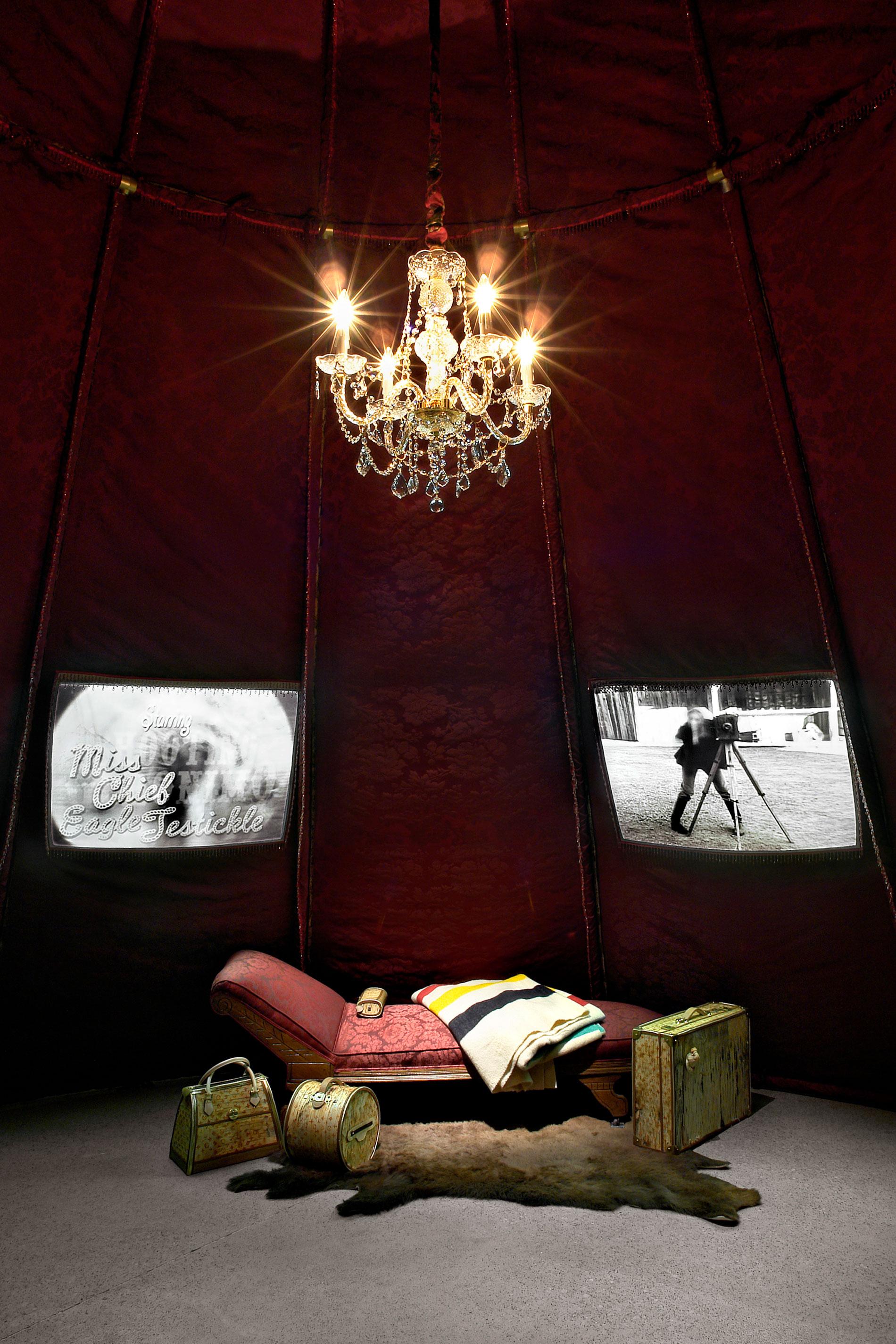

Canadian First Nations artist Kent Monkman’s installation “Boudoir de Berdashe“ resembles a teepee that’s not made of animal hide, but an elegant, red fabric. Instead of a log fire, a chandelier hangs from above. Two screens play short, silent films with a satirical take on depictions of American Indians.

Works like this take a western trope and turn it on its head and show how the classic genre continues to evolve, Smith says.

“Often we think of the western as a very simple story, and I hope this exhibition pushes idea that it was deeply complex,” he says.

“The Western” is on display at the Denver Art Museum through Sept. 10, 2017.