The term “border control” typically conjures immigration discussions on a national scale and images of walls and patrols on the U.S.-Mexico border.

But 85 years ago, Colorado closed its southern border and deployed a militia to stop other Americans in need from entering the state.

Denver Public Library historian Alex Hernandez uncovered the little-known history when he stumbled on some old newspapers at work.

“I like to go through [old newspaper clippings] sometimes and there’s this one for illegal immigrant labor and another for illegal migrant labor, two very similar things” Hernandez said. “I was wondering what the difference between the files were. One had a lot of material related to this border closure, and issues with borders being opened and closed is very timely, so I figured I would dive into this.”

Three weeks later, Hernandez had pieced together the puzzle.

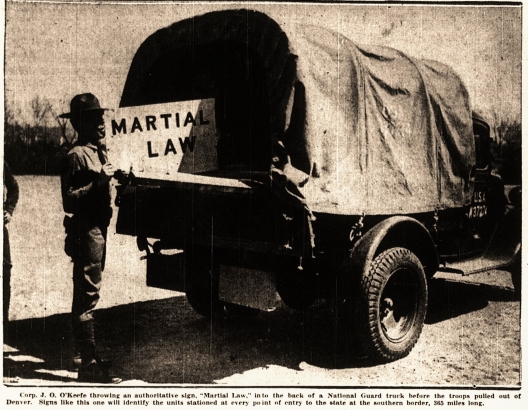

On April 18, 1936, Gov. Edwin “Big Ed” Johnson made an official declaration of martial law. He ordered the Colorado National Guard and state militia to patrol the state’s southern border. All cars and trains on major arteries were stopped and searched.

Hernandez said he sees parallels between ongoing immigration debates and the past.

“History is constantly repeating itself,” he said. “In this case, when any group of people get stressed or feel their resources are strained whether that’s real or imagined, their perceived tribe seems to shrink in size and more and more people become the other.”

“What we see now tends to be ethnic minorities, but as we saw in the Great Depression, it can easily be white Americans who happen to be from another state or from the wrong socio-economic class.”

As the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl ravaged the country, the national government encouraged people to move out West and to try dry-land farming using irrigation systems.

Much of the topsoil in the Great Plains had eroded and blown away because of poor soil management. People were rendered destitute as farms collapsed, and many were dying from “The Dust Flu,” which impacted a lot of children.

A mass migration out of those regions began as people searched not only for work, but also for clean air. Many were drawn to Colorado because of the state’s sugar beet industry that managed to stay unaffected by the worst dust storms.

But Johnson felt that those jobs were owed to Coloradans and Coloradans only. He even told people within the state to not support businesses who used outside labor, and encouraged Coloradans to observe and report anyone who appeared to be looking for work.

There were some exceptions. Anyone who appeared to be wealthy enough to come to Colorado for commerce or tourism reasons was allowed in. However, that designation was subjective and up to the state militia’s discretion.

People coming to find work were called ‘aliens’ and ‘undesirables.’ The states that were targeted in particular included Texas and Oklahoma, and some anti-Mexican sentiments also entered the rhetoric.

People who didn’t want to end up in Colorado, but needed to pass through to get to Wyoming and Montana, were also turned away.

Sugar beet producers relied on seasonal laborers and were having trouble recruiting people within the state to work.

The migration ban didn’t last long — only 10 days. New Mexico immediately condemned Johnson and threatened to boycott Colorado businesses.

New Mexico Sens. Dennis Chavez and Carl Hatch said it was unconstitutional. They cited article 4, section 2 of the Constitution: “The citizens of each state shall be entitled to all privileges and immunities of citizens in the several states.”

Editor's note: This story has been updated to reflect that 85 years have passed since this action.