They fought in wars, climbed mountains and survived a depression, recessions and at least six previous U.S. epidemics. They built families and businesses and inspired their communities. Combined, their time on Earth spanned more than four centuries.

All of their lives were ended by the coronavirus. They left behind mementos like a worn Denver Broncos jacket, a poem about Heaven and a 25-pound cat named Baby.

In the last year, Colorado has lost nearly 6,000 people to COVID-19. Nearly half died in nursing homes. More than 75 percent of them were older than 70.

The death of each left a void for family and friends, neighbors and roommates.

Here are some of their stories.

Frank Lloyd Kramer: "Made me want to be even more generous with people"

— Claire Cleveland

For Frank Lloyd Kramer’s 65th birthday, he and his daughter, Liz Myslik, hiked Mount Kilimanjaro.

“It was a long hike, it's seven days, and we slept in tents every single night. And this was paradise for him,” Myslik said. “Every day we hiked all day and talked and he shared memories and stories, and we laughed and we struggled.”

The night before they were supposed to summit, they ate Kramer's favorite food — popcorn — and it turned on him. Digestion is slowed at high elevations and he couldn’t make it to the top.

“He had such a horrible, upset stomach, and I was in agony because I didn't want to go without him,” Myslik said. “I was crying, and I said, ‘but I can't go without you.’ And he said, ‘yes, you can.’ He said, ‘I'm already the happiest man in the world because it's been the journey that has been the gift for me, not the destination.’”

That was how Kramer lived his life. And as Myslik looks back on that trip and her memories with him, that’s what she thinks about, “the way that he treated others and the way that he gave and expected nothing in return that taught me what it means to be a good person and the kind of person that I aspire to be.”

Back at the beginning of the pandemic, in March, Kramer caught the coronavirus. In April, he was admitted to St. Joseph Hospital in Denver. A few days later, he was transferred to the ICU and placed on a ventilator. Frank Lloyd Kramer died on April 27, 2020. He was 77 years-old.

His daughter got to be with him in the hospital, while his wife, Lynn Sauve, video conferenced him from her car in the parking lot.

“We were able to be with Frankie and support him during the last half hour of his life and to help him and be with him during his transition,” Sauve said. “It was actually a very, very beautiful and loving ending.”

Kramer was many things — an avid outdoorsman and traveler, a Vietnam War Veteran, a volunteer with the CASA organization that assigns volunteers to court cases of children and a venture capitalist — but his dearest passion was for writing poetry. He focused on children’s poetry, but he also wrote poems about his life and dozens of letters to Myslik.

He met Lynn, the love of his life, when her coworker stood her up.

“It was a Thursday night in October of 1996 and I was at the four-story restaurant,” Sauve said. “He started to look at me and then he came over and said, ‘don't I know you from somewhere?’ And I thought, oh, no, not on a Thursday night. He’s hitting me up.”

Kramer approached parenting with humor, once removing Myslik’s door when she refused to clean her room, and his poetry was funny and witty. One of his wife’s favorite memories is when Kramer read a poem called “Eat a Car” to his grandson’s preschool class.

“He didn't like to say, ‘Oh, hi, sit on a chair next to me and read a book,’” said Brady Myslik. “He was like, ‘let's go hide from your parents.’ And I always thought that was so funny and like weird because like no one else did that.”

Kramer shared his love of writing and his zest for life with everyone he could. A longtime friend of his who illustrated some of his poetry books for children said he encouraged her not to rob the world of her gift of painting, but rather to share it. She remembers a lunch with Kramer at Racine’s restaurant (now closed) where she was complaining about money and he told her to write a check on a napkin to herself. Amount: The sky’s the limit. For: Anything your heart desires.

“Frank made me want to be even more generous with people — my time, my energy, the things that I own, food, clothing, whatever. Frank just exuded generosity,” said Vickie Krudwig. “Having that check was just always a reminder that everything I needed would be there.”

As the anniversary of his death nears, Sauve looked through their computer and found a poem he wrote in 2011 that she had never seen before called “Heaven Found.” She shares it here:

Sit for hours with birds and flowers, mountain streams and morning dew

Lay for days beneath the haze of evening skies dimming blue

Nestle into nature's womb where ecstasy and bliss abound

Skip the trip to the earthly tomb for here at last is heaven found

Luis Villagomez: "I always thought he was gonna come back"

— Elena Rivera

Teresa Villagomez will always remember the way her husband, Luis, loved the La Garita Mountains, a range within Colorado’s southwestern San Juan mountains.

"He would have been there day and night if he could have," she said.

The mountains became a tradition for this family from Center in the San Luis Valley. If there was one special place, sister-in-law Maria Villagomez said, it would be in the state’s rugged higher elevations.

"All the brothers would get together. They'd wake up early in the morning, sometimes they'd make burritos," she said. "They'd go up there to cut wood, sit and eat, then load up the trailers, come back home, eat again."

Five years ago, Luis started to have liver problems. He was in and out of the hospital, waiting for a liver transplant when he contracted the coronavirus last May. He died on May 28, 2020, at the age of 61.

Beyond the mountains, family was one of the most important things in his life. Luis met Teresa in 1982. They later married and adopted two children. Maria and Teresa's families would get together often for holidays and birthdays.

"He'd grill outside for us or fry food on the disco," said Maria Villagomez. "He liked grilling meat and vegetables. And of course, food is always the main thing that brings families together. So we did a lot of that while our kids were growing up."

Luis also helped raise his siblings, many of whom he helped bring over from Mexico. All of the basics were covered; how to cook, how to make tortillas and how to work.

"He had them in [his home] until they were able to go out into the real world. He was the oldest. He took it upon himself, 'I was a migrant, now it's time for me to settle down and start bringing over some of my family members, and teach them what they need to be taught so they can survive.'"

Even as he got sick, he still made time to fish and spend time with his family — though it became less about the place and more about time and people.

"Towards the end, it's whatever his brother liked, if there was a new lake that his brother wanted to share with him, he'd go there and he'd enjoy it," said Maria Villagomez. "It wasn't about if you were gonna get carps, or if you were going to get rainbow fish or anything like that, it didn't matter if he came home with his hands empty. What mattered is that he got out with and he was with family. And that within itself was special enough to him."

Luis volunteered with their church, Center Assembly cleaning and going in the morning to build a fire in the woodstove. The congregation would have tamale nights as fundraisers and Luis loved making tamales alongside other women from the community.

Last May, Luis woke Teresa up in the early morning to tell her he wasn't feeling well. She called an ambulance. She remembers they didn't bring a stretcher for him, he just walked out of the house.

"He always wore his jacket. He has a Broncos jacket, always wearing it, and he forgot it," said Teresa Villagomez. "And I'm glad he did 'cause I would have never gotten it back. And it's hanging there and that's my time with him. I go and I hug the jacket."

Teresa also had COVID-19 at the time, so she was unable to go to the hospital with him.

"I always thought he was gonna come back. I did. And it just hurts me a lot not to be there with him at that time," she said.

The funeral was held over Zoom, where the family gathered together to say goodbye to Luis. Maria Villagomez said COVID-19 snuck up on their family, and grieving looks differently right now.

"I don't think until it's actually over, we will get to be together a little bit more as family members, and then we'll get to have some closure," she said. "So we look forward to the day we will be able to sit down and share those memories, have that time for each other."

'Tombstone' Ted Ruskin: "Death didn't hold a whole lot of terror for him"

— Natalia Navarro

The people who loved Ted Ruskin called him a renaissance man.

Well known for his silly jokes and activism, he gave freely of both his time and money toward causes he cared about from animals to music to memorials for the dead.

Theodore Paul Ruskin died from COVID-19 at age 76 on April 7, 2020. He is buried at Mt. Nebo Cemetery in Aurora, next to his partner’s grave.

A rabbi from the congregation he was a part of, Chabad Jewish Center of South Metro Denver, officiated a graveside service a few days later. Mourners watched the service over Periscope and cars lined the road outside the cemetery.

He was a cantor at a Denver synagogue for several years and an active member of temple philanthropy groups for decades.

“Judaism does put a value on what they call Tikkun Olam, repairing the world,” said Ruskin’s cousin, Libby Gershansky. “He took that value very seriously — making the world a better place, to the extent that you can. A better place than you found it. And I think that value was reflected in his life.”

Born in Brooklyn, New York on July 15, 1943, Ruskin would later move to Colorado in the 1970s where he worked as a teacher in a federal prison in Englewood. After retiring from teaching in the mid-1980s, he began designing tombstones — giving himself the nom de guerre of “Tombstone Ted.” He was the driving force behind the renovation and yearly cleanup of several Jewish cemeteries in the Denver metro that had gone into deep disrepair.

Ruskin also helped establish Babi Yar Park, which serves as a memorial for Jews who died in a Ukrainian massacre during the holocaust.

Though his work may seem morbid to some, Ruskin was far from somber or brooding.

“He was a lot of fun,” said long-time friend Paul Thomas. “He had a good sense of humor.”

Even as he went into the hospital on March 28, Ruskin was still cracking jokes.

“It was the damnedest thing,” Thomas said. “The nurse told me that he would make jokes on his way to intensive care. Death didn't hold a whole lot of terror for him.”

This wasn't the first time Ruskin faced death. The love of his life and partner of more than a decade, Gary Bobb, died of AIDS in 1994.

“They were together for a very long time and I know Ted loved Gary very much,” Gereshansky said. “If marriage were possible at the time that they were together, I'm sure they would have gotten married. I mean, they considered themselves married.”

Ruskin and Bobb met in the 1970s at a group for gay Jewish people. They shared a life and a love of classical music.

Both were caught up in a major American epidemic and friends saw their lives ended too early, before effective treatments were developed.

“Now, Gary probably would have been able to be helped, in the same way that Ted got COVID, but he got it so early that they didn't have all the different therapeutics that they have now,” Gershansky said.

For the last 40 years of his life, Ruskin slowly lost his vision to a rare, genetic and degenerative eye disease called Retinitis pigmentosa, which damages the back wall of the eye.

Thomas indulged Ruskin’s love of the opera and took him to Santa Fe to see three to five operas every year for 26 years. Toward the end, when he could only see shadows, he went to the opera simply to hear the music.

His favorite was Mozart’s Don Giovanni.

A lover of animals, Ruskin spent the last years of his life with a 25-pound cat named Baby. After his death, Baby was adopted by a loving friend.

Ruskin had a beautiful singing voice and good taste. He was creative and funny. He was generous to a fault and a loyal friend. He valued family and deep conversation.

“Ted was marvelous,” said Sara Wilcoxson, a volunteer with The Center on Colfax, Denver’s LGBTQ resource center, who visited Ruskin toward the end of his life.

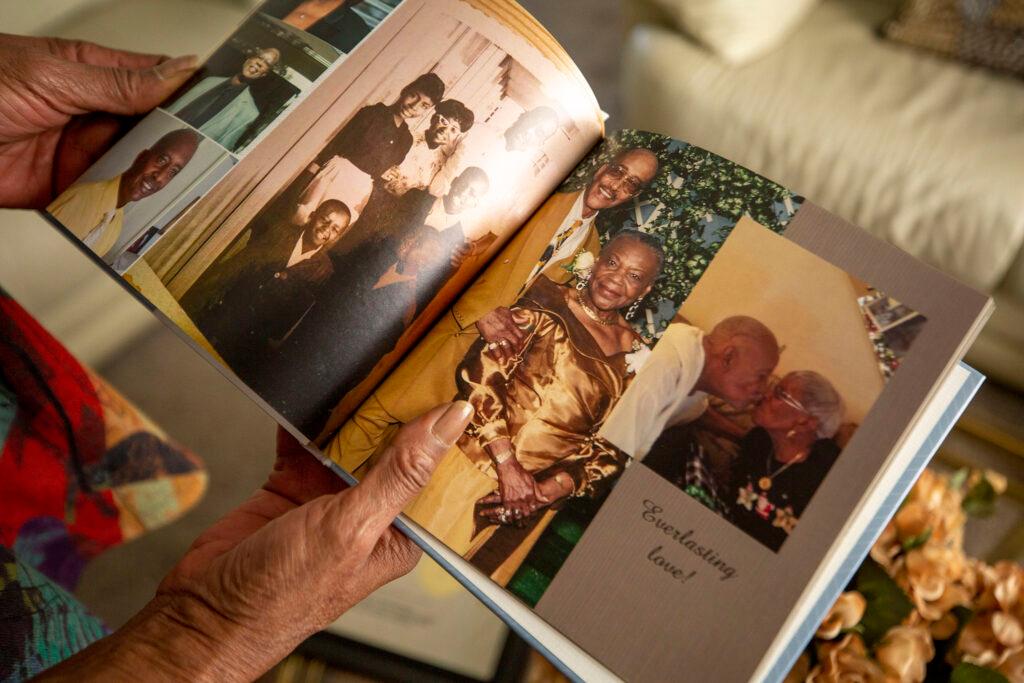

Jim and Dottie Russ: "Even after 60 some years, they still kissed a lot"

— Andrea Dukakis

Jim and Dottie Russ met in high school, married before either was 21, raised a family and left a mark in both Pittsburgh and Denver.

Then came COVID-19. The couple who were inseparable for 70 years were both gone fewer than 70 hours apart.

They died at Denver’s Holly Heights nursing home, where one was rarely seen without the other, and, when they were apart, the staff was put on notice to reunite them quickly.

“If daddy was missing too long, mommy would go to ask them, well, where's my husband. You seen my husband?” said their daughter Jeannie Davis.

The two were among about 2,500 people living in Colorado’s elder care facilities who died from the virus since the first known case of COVID-19 in Colorado surfaced a year ago. The vulnerability of older adults to the virus combined with a congregate living setting where the virus could spread turned out to be a fatal combination.

The Russes went to high school together in Pittsburgh and were just 19 and 20 years old when they were married. They had four children, daughter Jeannie, followed by three boys.

Jim was the breadwinner, working first in a shoe store, then arranging mortgages for homebuyers in Pittsburgh’s Black community where he was responsible for getting countless people into their first homes, and pushing back on the city’s color lines in the process

While Jim made the money, when he got home, Dottie was the boss.

“She ruled the roost with him,” Davis recalled. “Very few [people] would have guessed [because] he was 6’3” and she's only 5’2.”

Davis left Pittsburgh 45 years ago to move to Denver for work but her parents remained in Pittsburgh until their health started declining a few years ago and they came to Colorado to live with her.

Shortly after they arrived in Denver, Jim Russ received a proclamation in 2017 from the city of Pittsburgh for his help with the Black community in his hometown. The Russ’ are Black and Jim Russ, who was in real estate, saw an opportunity to help others buy houses with loans from the Federal Housing Administration, said Jeannie Davis.

“Because it was difficult for minorities to acquire property and ownership back in that day.”

Jim and Dottie Russ also were honored posthumously with a plaque for their contributions to Pittsburgh.

Despite her parents’ traditional roles, they divided a lot of the work at home.

“She did all the cooking. He did all the grocery shopping,” Davis explained. “He shopped for her clothes because she could never make up her mind what she wanted and he wasn't going to be in that store for three days. [He’d say} ‘We need to get what you want and get out of here, Dot.’”

Davis' father liked to dote on her mother, bringing her flowers even if it wasn’t for a special occasion. And she said they weren’t afraid to show their love for each other.

“They kissed a lot. Even after 60 some years, they still kissed a lot,” Davis recounts smiling. “Not throaty, but you know, the peck on the cheek and all of that.”

Davis said she was brought up to value family. She remembers when she moved her parents to Denver that they feared she was putting her life on hold to care for them.

“My response to that was simply, ‘What are you talking about? You raised me, you taught me how to walk, how to talk. You taught me how to be independent, how to lead and not follow. I’m here for the long haul.’”

Eventually, her parents needed more medical care than Davis could give them at home, so she moved them to Holly Heights nursing home which was close-by and easy to visit. She said the staff there became family.

But on March 10, the advent of COVID-19 meant the doors to the facility were locked and she couldn’t visit.

Instead, she and her parents learned how to talk by video chat, which Davis said was surprisingly fun though she missed getting to see her parents regularly and hug them.

In early April, the nursing home announced an outbreak among residents and dozens of residents and staff got sick.

The two seemed fine until April 9. They went to breakfast and after, Dottie went to play Bingo while Jim went back to their room to watch westerns.

“Then, right around [noon], the [nurse] went to get them for lunch and they were totally lethargic,” recounts their daughter. “It was like, I'm told that they were hit by the same arrow. At the same time.”

Davis got special permission to visit in person one more time. She donned PPE and went to their room to see them but they could hardly talk and seemed to go in and out of consciousness.

Dottie died on April 16. Then, a couple days later, Jim died. After each of their deaths, Jeannie Davis thinks she heard from them.

“The day after mommy passed away, I woke up that morning and there was a rainbow in my bedroom,” Davis said. “The day after my dad passed away, there was another rainbow in my bedroom.”

She said she had lived in her house for 29 years and had never seen a rainbow. Davis said she felt they were telling her, “We’re here. It’s safe. We’re OK. We’re still together.”

Olga Archuleta: "She’ll be a role model for the rest of my life"

— Stina Sieg

Olga Archuleta encouraged everyone to be themselves.

That’s how her daughter, Ona Ridgway, remembers her. Her mom liked to fish and go to church (mainly to sing). She loved her children and animals and her late husband.

Archuleta was 91 or 92 when she died of COVID-19 on Dec. 2. Ridgway smiled as she explained that sometimes her mom said she was born in 1928 and sometimes said she was a year younger.

“So we just kind of laugh about it,” she said.

Born in Pueblo and raised in Trinidad, Archuleta married right out of high school and moved to Detroit. After the birth of her first son and while she was pregnant with her second, that relationship fell apart.

Her mom picked herself up and fell in love with Richard Archuleta, “Archie” everyone called him.

“He doted over her,” Ridgway said, fondly. “He loved her so, so much.”

It’s a marriage that would last more than 60 years. They left Michigan and moved to Pueblo, where they raised his son and her two boys — and had three more kids. Ridgway was the baby, born when her mom was about 40. She remembers her mother being “very nurturing, very protective.”

She also jokes that she was pretty radical.

“I remember as a teenager, she would talk to me about birth control,” Ridgway said, laughing. “She was just very open-minded for that generation”

When Ridgway’s sister, Chope, came out as transgender, Ridgway said her mom didn’t want to believe it at first. But then their parents consulted a priest, who told them: “It doesn’t matter what anyone else thinks, this is your child. And people will talk, and people will say things, but they’ll soon forget, as well. So love your child, the way God loves his children,” she said.

And that, Ridgway said, was a turning point for her parents. Ridgway also has a transgender daughter, who came out to her at 17.

“How I have chosen to parent this child, is how I feel that my mother would have chosen to parent my sibling at a younger age,” she said.

She feels her mother instilled in her a need to care for others. Ridgway is a nurse, and two of her siblings also went into health care. Her mom had wanted to become a nurse herself once, before life unfurled in a totally different direction.

Ridgway is happy that her mother was able to live close by for the last part of her life. Archuleta moved to Mesa County in 2012, initially with her husband, who died a few years later.

When Archuleta got sick with the virus right around Thanksgiving, La Villa Grande Care Center in Grand Junction let her daughter visit, a policy for residents nearing the end of their life. Even in full personal protective gear, Ridgway was surprised she was able to be by her mom's side.

“I’m grateful that I got to hug her and touch her and tell her in person that I love her,” she said.

Two days later, in bed with oxygen tubes in her nose, Archuleta wanted to send her daughter a message. She got her grandson, Ridgway’s son, who actually works at the facility, to record her with this phone.

The message was short, just three words: “I love you.”

Ridgway visited her mom two more times, but she faded quickly. Archuleta died early in the morning a few days later.

“She’ll be a role model for the rest of my life,” Ridgway said, her voice faltering, “hopefully a role model for my children.”

And her mother lives on, she explained, in all of them.

“You know, I’m just glad that I got to be her daughter.”

Editor’s Note: March 5 marks one year since Colorado announced its first cases of COVID-19. CPR News is reflecting back by checking in with some Coloradans whose stories we've shared during the pandemic. That includes coronavirus survivors, business owners, and faith leaders.