Activists pushing to restore environmental protections for a small creek in southern Colorado say they are disappointed by the state’s plan to take more than two years to review wastewater dumping by a nearby steel mill.

The group, which includes students from the University of Colorado Boulder’s environmental law clinic, environmental law attorneys and Pueblo residents, sent a letter to the state’s Water Quality Control Division in May demanding it review the water quality permit for the Salt Creek.

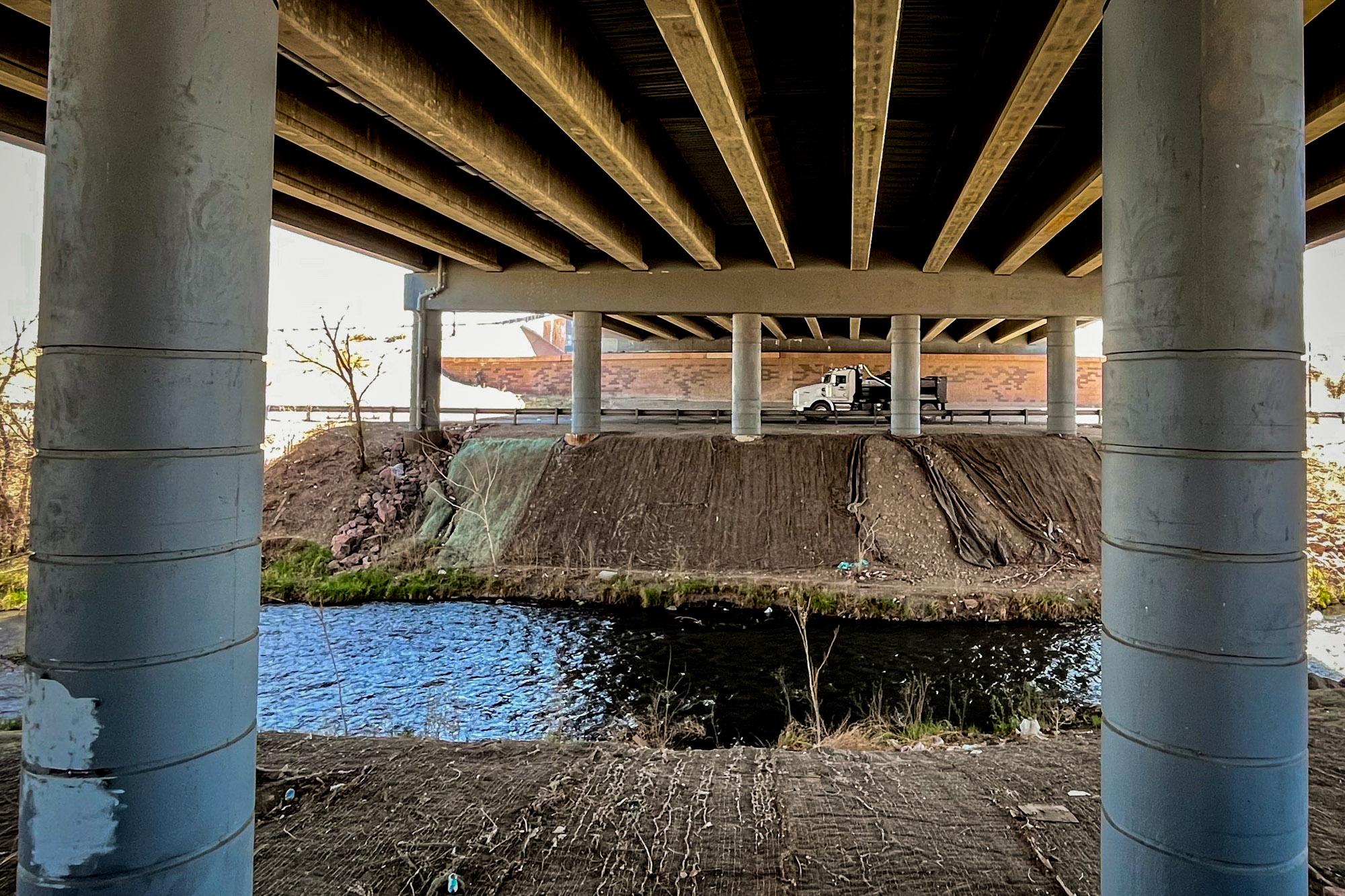

The Evraz Rocky Mountain Steel mill uses the creek, which runs through a small neighborhood of the same name, under an arrangement made more than 40 years ago that removed the creek’s designation as a state waterway. As a result, the mill doesn’t fully treat the water until it is discharged into the Arkansas River further downstream.

In a July 8 letter to the group, Water Quality Control Division Director Nicole Rowan said the agency would “carefully review the Evraz discharge permit” after updating water quality standards for the underlying basin in June 2023. It would then reach out to the Salt Creek neighborhood to get feedback on existing wastewater dumping before updating the permit at the end of 2024.

Velma Campbell, a Pueblo physician and volunteer with the local chapter of environmental nonprofit Mothers Out Front, said she was disappointed by how much time the state would take to inspect the creek’s water quality.

“They’ve had years — decades — to work on this permit,” Campbell said. “The permit itself has been outstanding for too long without renewal.”

The state stripped Salt Creek’s designation as a state waterway in 1979 after the mill’s owner at the time, Colorado Fuel and Iron, challenged stricter regulations for wastewater dumping. In 2018, the state and Evraz entered a formal agreement to “maintain the status quo regarding Salt Creek” and not set any numeric standards for the creek.

In their demand letter, the environmental groups argued the state had not renewed the steel mill’s wastewater permit in more than 10 years, or two five-year terms as is legally required. Campbell and other activists now say the state should cancel the agreement with Evraz that prevents the renegotiation of Salt Creek’s pollution limits.

“We’re specifically frustrated that the Water Quality Control Division isn’t taking an action at this time to invalidate that [agreement],” said Ellen Kutzer, a senior attorney with environmental nonprofit Western Resource Advocates. “From our perspective, this is something they can do now.”

The timeline outlined in the agency’s response to the environmental groups' demand does not change the standard review process for water discharge permits, water quality division spokesperson Erin Garcia said.

“The department is committed to working closely with the community; providing materials in a timely manner in a variety of languages; hosting meetings at times that work for community members; and engaging with local community groups to reach a larger audience,” Garcia said in an email.

The division followed a similar process when it began to review a water quality permit for the Suncor oil refinery in Commerce City last year. Campbell, the Pueblo physician, wants the state to communicate with the Salt Creek residents throughout the review process.

“The Salt Creek situation and how it’s been handled over time is a very good example of an environmental justice issue, in which the community has not been kept well informed about what’s going on,” she said.

Salt Creek has fewer than 1,000 residents and is almost entirely Hispanic, according to five-year estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau. Its residents over the decades have rallied against poor water quality, dirt roads and lack of public transportation. The creek used to run black with oils and contaminants from the steel mill, according to a local newspaper article from 1971.

An Evraz spokesperson did not respond to a request for comment.