Mark Felding has attended Temple Emanuel on Pueblo’s Northside for 18 years, going weekly to the family-style synagogue that serves about 35 families and seats 200.

But when a genetic health condition left the 54-year-old susceptible to pulmonary embolisms a few years ago, he had to stop working as a paralegal and go on disability. He uses oxygen from a tank, and often uses a wheelchair to help him move around comfortably.

That’s a problem for his ability to attend 122-year-old reform Temple Emanuel.

“I cannot use my wheelchair there, because there’s no ramp…there are numerous steps,” Felding said. “You’d literally have to push it up through the foliage somehow, and it just wouldn’t work.”

But fixing that problem is complicated by the age of the temple, its unique design, and its inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places.

It’s all solvable, but it will take lots of money, and the landmark south Colorado temple has now embarked on a fundraising campaign to help their disabled congregants.

Michael F. Atlas-Acuña, 72, president of the temple’s board of directors, has taken on the challenge of helping Felding, about 14 other regulars, and also guests.

“The reality is that the majority of the people that would need it would be coming during our High holidays, during Yom Kippur, Rosh Hashana, bat mitzvahs, weddings, life cycle events,” he said.

That’s not something that was factored in when the temple was built 122 years ago, he said with a laugh. “You know, in 1900, they’re not thinking about ramps!”

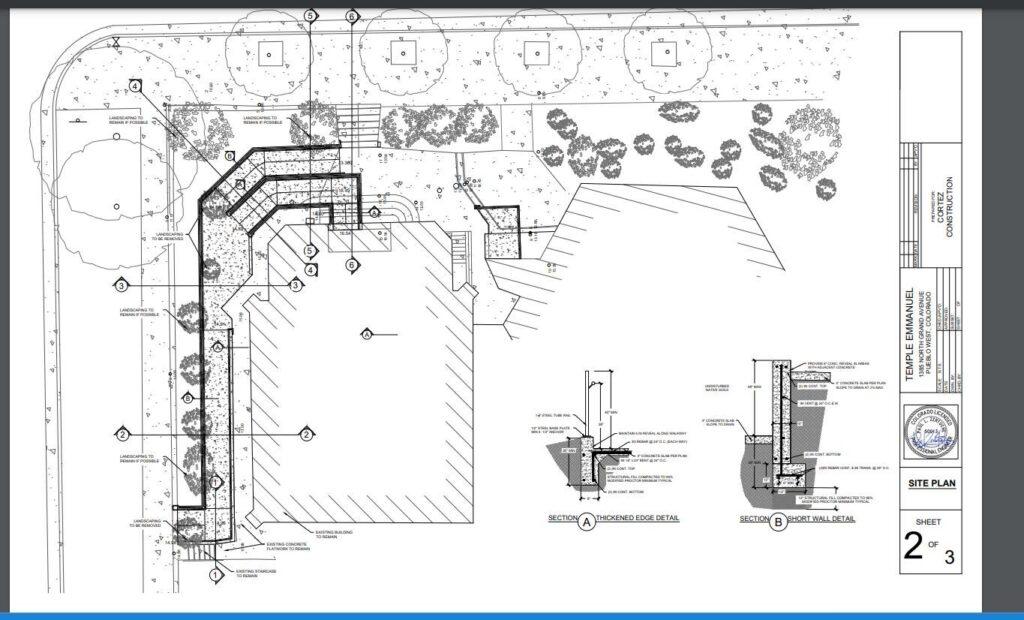

In April as he was earnestly trying to solve the problem, he realized it was complicated by two factors. The building is on the registry of historic buildings, and therefore, he wants to keep the facade looking the same. The Victorian styling would be compromised by something really visible, so his goal was to come up with a ramp that could be obscured by landscaping and made of concrete and metal, without materials that would need maintenance. Also, the ramp couldn’t be too steep in order to comply with Americans with Disabilities Act regulations. With the many stairs leading inside, that made it tricky.

So he reached out to a few design engineers. The first ones couldn’t come up with a plan that met all of the temple’s different needs. Then he came across Paul Zertuche, 48, a design engineer at the Pueblo-based Pablo Engineering, where he’s the sole employee.

Zertuche found he had a puzzle on his hands. He already knew about the temple and had respect for the members, so he decided to donate his time and waive his fee, which would have been several thousand dollars.

“They have very little room,” Zertuche quickly discovered, and he had a lot of factors to consider. “You’re limited on your steepness by ADA rules … They have regulations on how steep you can have them.“

Keeping in mind materials and appearance, he spent a month taking measurements and trying the different ideas until he came up with a design that would meet all the building’s needs by accessing an entrance on the north side with a ramp about 20 feet long. The only problem: the estimated price tag was about $160,000.

Atlas-Acuña was not deterred – he was accustomed to turning temple-based challenges into blessings. In 2019, a white supremacist planned to attack Temple Emanuel with pipe bombs and dynamite. The FBI was tipped off when the then 27-year-old unknowingly communicated his plans over Facebook to an undercover FBI agent. He is now serving a 19-year sentence.

It made national news, and when a journalist inquired about the absence of cameras for security, the public found out and started chipping in.

“I never asked for money, but the money started coming in and we ended up collecting $11,000,” Atlas-Acuña said with glee. “That guy that tried to blow us up, he ended up giving us a gift!” Now, he said, the temple has a sophisticated camera system he can access from his phone.

Since then, Atlas-Acuña has retired from a non-profit organization in Pueblo serving those with developmental disabilities, where he worked in various roles for more than 40 years. While he continues to run a window-washing business part-time, he’s looking for a way to turn this problem into something positive, like he did with the bomb scare, by trying to shore up funding from wherever he can get it.

Doing it will require some ingenuity, but temple members have plenty of that. They have spent years working around the lack of a ramp.

“If someone was trying to get into services and couldn’t walk steps, a group of people would go down and lift the wheelchair up the steps into the congregation so that they could join us,” said Rabbi emerita Birdie Becker, who served from about 2000 until 2019 and still comes for special occasions. “I mean, people in the congregation helped each other.”

But they couldn’t always help Felding, who uses a hybrid semi-powered wheelchair, large enough for his 6’1” frame. The chair is too heavy and cumbersome to be carried in, even with a few members helping out. So Felding, who lives alone, sometimes must miss Friday shabbat meals, winding up stuck at home reading the Torah by himself. “I think of these people as my family, as all my friends, and I miss seeing them when I’m not able to attend in person,” he said.

Already, there’s some money on hand. The building needed some structural upgrades – repairs to everything from bricks to paint to stained glass – and the temple did some fundraising, gathering about $80,000 for the repairs, which congregants made with about $10,000 to spare. Additional fundraising from synagogue members brought the total up to about $40,000 – only a quarter of the amount needed. With inflation, Atlas-Acuña is concerned that the cost could jump to $200,000 before he’s ready.

So next up is a fundraiser, one with a Temple Emanuel-style twist.

“On December 11th, we’re having a program with Klezmer music,” at 3 p.m. in the temple, Atlas-Acuña said, describing that musical style as traditional to the Ashkenazi Jews of Central and Eastern Europe, with the temple’s style focusing on accordion, piano, violin and conga drums. “We spice it up,” he mentioned in an e-mail.

He will play congas and other instruments as part of a trio. The event will also feature an appearance by an actor playing the ghost of Abraham Goldsmith, a Jewish pioneer who came to Pueblo in 1864.

Charging no admission at the fundraiser is a strategic decision for Atlas-Acuña.

“We ask for donations, and what we have found is that people are more generous when you ask for donations as opposed to asking for an admission fee,” Atlas-Acuña said. “So that’s how we’re handling it.” When asked if he’d be going to the fundraiser, Felding said, “Health permitting, I will be there.

The temple has also applied for grant funding from the New Mexico and Colorado Jewish Federations, with the help of Felding, who volunteered his knowledge of writing grant applications.

And now as they wait to see if they receive it, Atlas-Acuña sees something good coming from the music and theater fundraiser.

”After the bombing, our Facebook page blew up with a bunch of people who wanted to befriend us, and one of our friends from Texas said to us, ‘You are the little shul that could,'” Atlas-Acuña recalled.

If the temple is able to raise enough money, the design engineer Zertuche would then hand the plans off to a sub-contractor who would fabricate his ideas into a ramp that would allow Felding and other regulars, as well as guests, to come inside to worship and socialize.

“We want the ramp to be available to everybody,” Atlas-Acuña said. “It’s a public place, like any public place, we want it to be so that anybody can get into the building.”