Since the late 1990s Colorado has tried to expand access to high-speed broadband. It’s been done in starts and stops, and sometimes not at all.

Silverton, in San Juan County, is a prime example.

“A) we're not a large customer base. B) it's really hard to get here,” said Deanne Gallegos, executive director of the Silverton Area Chamber of Commerce, who’s been involved in trying to get the town and county connected for years.

Perched in the San Juan mountains, there isn’t a huge year-round population, just under 800 in the county as a whole. But a million tourists pass through and for businesses and economic development high-speed internet is key.

“The constant conversation for how do we grow our future, how do we grow our population seemed to always center around reliable internet service and hopefully someday having access to high speed internet service,” Gallegos explained.

Now Colorado is getting a huge amount of federal money, more than $826 million in Broadband Equity Access and Deployment (BEAD) funding that was part of the 2021 infrastructure law to help expand broadband internet across the state and the country.

It’s been a goal of countless lawmakers at the local, state and federal level for more than two decades, yet there are still thousands of households that lack access, as Governor Jared Polis noted last month. “Right now there's about 190,000 Colorado homes and businesses that have very limited access, low access, or no access at all,” Polis said in July.

Past attempts to connect all corners fell short

In 2000, then Republican Gov. Bill Owens touted $37 million for U.S. West — which then became Qwest, which got acquired by Centurylink, which is now Lumen — to connect all county seats within 10 years. It was nicknamed “the beanpole project.”

Ten years later, Silverton still didn’t have high-speed access. The fiber cables were about 16 miles short of the town when funding dried up.

In 2010, when Democrat Bill Ritter was governor, the state received $100 million from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act to connect almost 200 school districts. (That project was called Eagle net). So in 2014, helicopters placed fiber lines along electrical lines to try and connect to Silverton. but even that fell short.

“That got laid all the way just outside of town,” Gallegos recalled with a chuckle. “And now we as a community are responsible for figuring out how do we tether to that amazing opportunity that's just right outside of our town.”

Sen. John Hickenlooper, the state’s former governor, said geography has been a challenge. “Colorado's full of box canyons and you go from the plains and then suddenly you're in the hill country, then you're in mountains...So we end up having to run more fiber longer distances than maybe some other states would.”

It’s a literal embodiment of what many call “the last mile problem.”

For so long we have struggled to convince providers to build that last mile,” said Democratic Rep. Joe Neguse, especially in hard to reach places. Despite past promises that failed to deliver, he sees the $826 million from the infrastructure law as a game changer, “because now the federal government, by virtue of the investments we are making, will ensure that that last mile is connected.”

It took almost a quarter of a century, but Silverton was able to get another provider besides Centurylink, now known as Lumen, in and there is some high-speed internet available, but it’s still not everywhere. For example, the Visitor’s Center still relies on the old dial-up system, which is currently out. And Gallegos said Centurylink wouldn’t be able to send a technician to fix it until September.

“It kind of all almost forces you to start exploring the other options in our community,” she said.

A spokesperson for Lumen said the company is committed to expanding broadband availability.

“We’ve made significant investments in our network to bring broadband access to every corner of our service territory where it is economically feasible,” said a statement from the company, noting rural areas can be difficult to service due to building and maintains the network. “We strongly support closing the digital divide and will continue to work with policymakers to ensure that this support is targeted to the areas that need it most.”

Money is just one obstacle to spreading broadband across the state

A plethora of three- and four-letter state and federal agencies have spent millions of dollars expanding high-speed internet across the state: DOLA, the BDB, the FCC, NTIA and USDA to name a few. And since the pandemic, the number has grown larger. The state has received $1.2 billion to beef up high-speed internet access.

The big question now is how to best use those funds to get all of the state connected. As past attempts have shown, money has been just one obstacle to spreading broadband across the state. Another has been figuring who to work with; Early attempts focused on big internet providers to do the work.

“We kept subsidizing the largest telecommunications companies in America,” explained Democratic Sen. Michael Bennet, “and said to them, to the tune of $50 billion, ‘Please go out there and build broadband for the American people.’ And they never did, especially in rural America.”

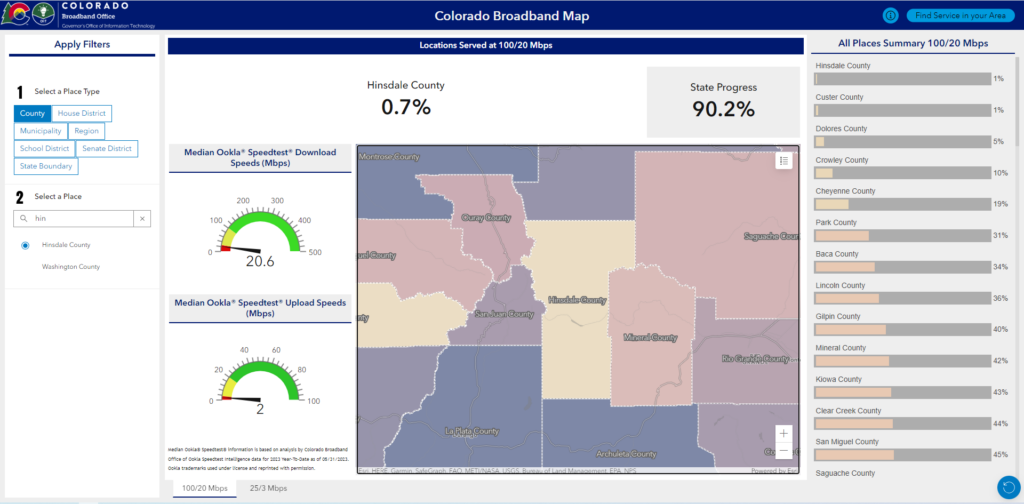

Over in Hinsdale County, another sparsely populated remote county, about one percent of homes and businesses have 100/20 Mbps, while just under 60 percent have 25/3 Mbps, per the Colorado Broadband Office’s map. (The first number is the download speed and the second is for uploads).

Commissioner Greg Levine, who manages the broadband portfolio, said big companies like CenturyLink didn’t give communities what they needed. Instead, the communities got what they got.

“We were like peasants, you know, just begging for scraps,” he said. “And why no providers were willing was that we're just not a market share. It's not a profitable market. It doesn't attract big companies.”

And there could be barriers to luring smaller companies to the market. For example, Centurylink didn’t give other providers much access to the lines they used taxpayer funds to put down.

The way Silverton’s Gallegos described it, Centurylink created a 20-lane broadband highway, but only two of those lanes were open to other providers. Levine worked with other small communities and regional organizations to get another provider interested in bringing service. But he added, there also needed to be some kind of financial incentive.

“I hate to say it, subsidizing them, giving them a whole lot of money to come in and give us a 20-year contract for services,” he said.

Local governments get involved, despite early attempts to keep them out

Another hurdle was a state law. In 2005, Colorado passed SB-152, which prevented local governments from entering the broadband market, unless voters said otherwise.

“We very much viewed it as being friendly to telecom companies,” said Nate Walowitz, regional broadband director for the Northwest Colorado Council of Governments.

He said the law was a legal impediment to communities fixing broadband problems that incumbent providers weren’t addressing. In the end, more than 100 communities got voter approval to get around the bill and this year the legislature finally did away with the election requirement.

For Walowitz, it led to the creation of Project Thor, a 481 mile internet network built by the Northwest COG.

“We had to go it alone and build a regional fiber loop across our region and connect back to Denver so that we could buy broadband bandwidth at Denver prices, which weren't being provided by the incumbents in our communities,” he explained.

The group partnered with the Colorado Department of Transportation to lay fiber along I-70. The focus for the group is the middle mile. They work with internet service provider partners who get the last mile done.

Several local governments and regions have dipped their toes into these broadband waters

Bennet said the ability of local leaders to get things done was something he saw early on. He pointed to the success of regional groups like the Delta Montrose Electrical Association.

“They had figured out how to do it and how to supply broadband in ways that almost no community across America had done at very high speeds for their constituents,” he said.

Different regions and communities have handled it differently. Brandy Reitter, who heads Colorado’s Broadband Office, said there is no one-size-fits-all solution.

“You have some local governments that will embark on their own community network, but more often than not, we see a public-private partnership, especially in the areas that are really hard to serve, because they're really hard to scale. And for some local governments they can’t afford to do that,” she explained.

And that’s where the recent flood of federal dollars comes in. Reitter described it as a “once in a generation” opportunity. She’s excited about what this funding could do for the state. But she’s also trying to manage expectations about how soon people should expect to be able to unplug their modems.

“When you look at it, it takes approximately two years to complete a fiber project. And that's if all the permitting goes well,” she said.

The large amount of federal money may be the final piece of the puzzle, but Hinsdale County Commissioner Levine acknowledged unlocking it may still be challenging for small local governments, especially to meet the reporting requirements that come with it.

Still, Levine anticipates that’s going to be the focus for a lot of local leaders now — how to go after this windfall of broadband funds.

“I’m very grateful that all this money's flowing into our state,” he said, “And I just need to learn better how to access it ‘cause I often say it is like a cake behind glass and it's there, but I need to break that glass. I need to lift it up and get to that cake.”

Editor's note: The story was updated Aug. 23 with comment from Lumen.