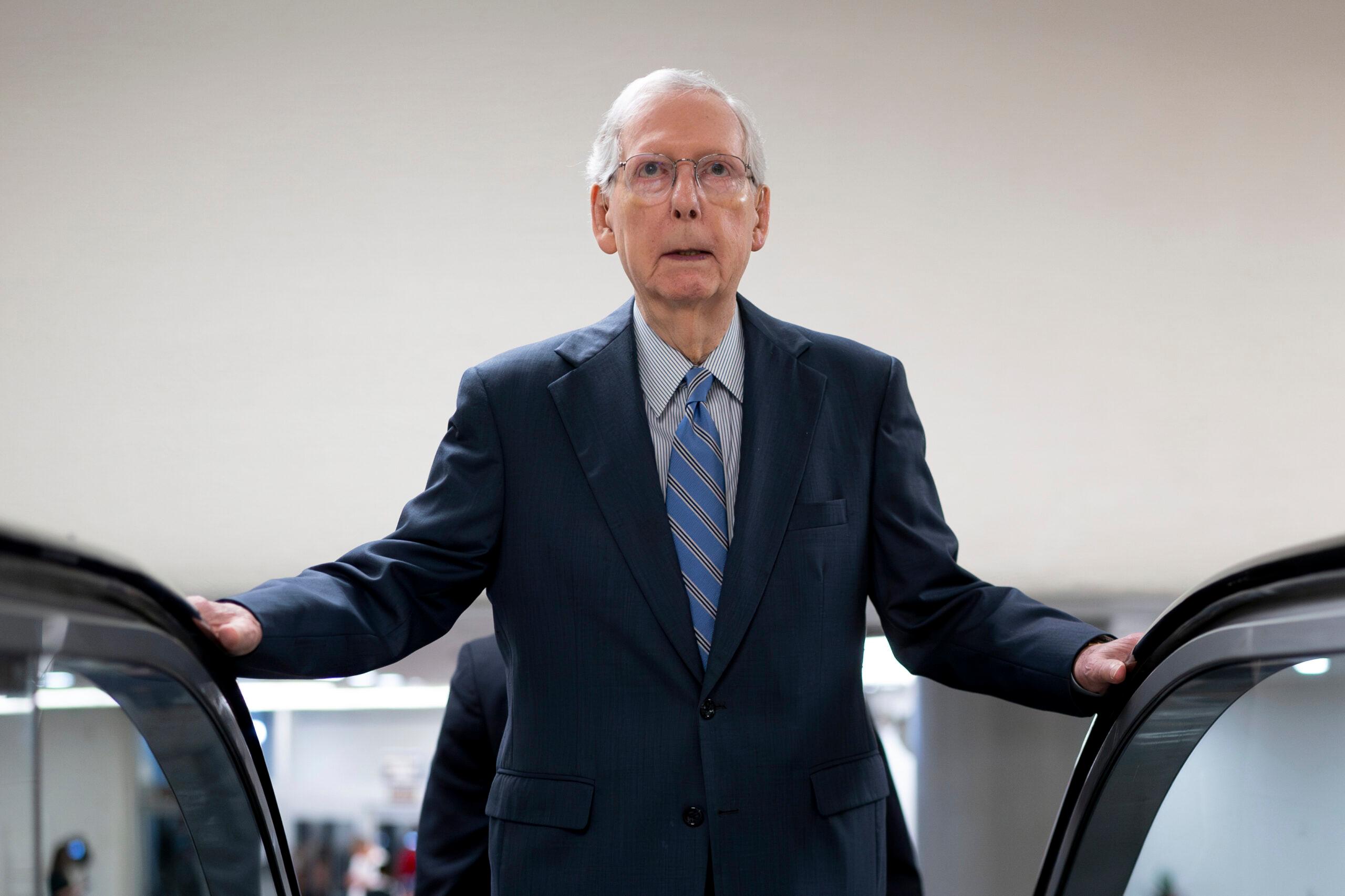

The founding fathers set a minimum age for when people are allowed to run for federal office, but when it comes to the issue of a maximum age limit, they were mum.

It’s an issue that has come up as questions have swirled around the health of Sens. Mitch McConnell, 81, and Dianne Feinstien, 90. In the 118th Congress, the median age of Senators is 65, while in the House it’s almost 58 years old.

A maximum age limit for some types of work is not unheard of. There are mandatory retirement ages for airline pilots, the military, even for state court judges, (Colorado’s mandatory judicial retirement age is 72.)

Still, when it comes to whether any age is too old to hold public office, Colorado’s congressional delegation seems to have found some common ground: They don’t think there should be a mandatory age limit.

Democratic Rep. Jason Crow, 44, thinks it’s a question best left to the voters.

“I don't like the idea of putting an age limit on something like an elected position because there are people who have served for a very long time that are in their senior years who are remarkable members of Congress and extremely high performing. And there are younger folks who I question, frankly their lucidity and their stability,” he said.

Letting voters decide whether a politician is too old to serve was a common refrain.

Dean of the Colorado delegation, Rep. Diana DeGette, 66, looks at politicians like 83-year-old Nancy Pelosi, who recently announced she will run again for office, as an example of what would be lost with a mandatory retirement age. Pelosi “is still 150 percent there, she's still helping with strategy. She's still active, she's still effective.”

Like Crow, DeGette noted there are people years younger who aren’t as effective, and it should be up to voters to choose who they want to represent them.

Democratic Sen. Michael Bennet, 58, said, “there are people that have been here for a really long time, whose wisdom the American people benefit from. And there are people that have been here for a really long time that I'm not sure who they're benefiting.”

He concluded, “we probably are better off just letting the American people make the decision” and for him, one element of that is reforming the campaign finance system to make political participation more fair.

Instituting a one-size-fits-all solution via an age limit, added GOP Rep. Doug Lamborn, 69, “isn’t a good way to run a country.”

Republican Rep. Ken Buck, 64, said he’s given this issue some thought and doesn’t believe an age limit is appropriate. The problem, he laid out, is that there are some 80-year-olds who are energetic and sharp “and to say they can’t serve because they’re a certain age is ridiculous.”

But he wonders if there couldn’t be some other way to ensure the people serving are up to the challenge, like how the FBI and the military have physical fitness requirements.

“I don’t know what the answer is,” Buck said. “It’s a very complicated answer, but we leave that up to voters, that’s the key. Voters are able to judge, is someone healthy enough to serve in office?”

Freshman Rep. Yadira Caraveo, 42, also thinks it’s a question each lawmaker has to ask of themselves as they age. “(What) I would hope is that people can just be cognizant of when it's time to move on.”

The pediatrician likened the considerations to the medical profession, where there is no mandatory retirement age, but practitioners have an ethical obligation to leave when it’s time. “I think that doctors are very good at knowing, ‘I make life and death decisions, and I should know when I've slowed down to a point where maybe it's not a great idea for my patients anymore.’ I would hope that it's the same thing here. That people would be cognizant of it's time to pass the torch on to the next generation.”

Fellow freshman, Democratic Rep. Brittany Pettersen, 42, thinks term limits, rather than age limits, might be an approach. But she’d like to see people allowed to serve longer than the eight years allowed in each chamber of the Colorado State Legislature, which she thinks gives lobbyists more power. “There’s a time at which it’s time to step aside and make way for the next generation.” Pettersen noted the man she replaced, former Rep. Ed Perlmutter, did just that.

Perlmutter, 70, said he thinks an maximum age limit would be unconstitutional, and like others he thinks voters are the ultimate judges of someone’s fitness for office. But he added politicians also have to decide for themselves, like he did. He said he listened to his own “internal clock,” and when it told him enough is enough, he decided to step down in 2022.

It helped, he said, that there was a good bench in Colorado. “You’ve got to let the bench rise. You can’t say to somebody, ‘Oh, you’re doing great, but it’s not your turn yet.’”

He added retired lawmakers could always serve as informal advisors for those still serving. As he said with a chuckle, “there is life outside of Congress,” including interesting and rewarding work.

The oldest member of the Colorado delegation, Democratic Sen. John Hickenlooper, 71, agreed retirement is less about age, and more about supporting new blood in Congress.

“I definitely think there should be ways to encourage more turnover and maybe that's a two term or three term limit for senators. Something that allows us to let the process reinvigorate itself,” he said.