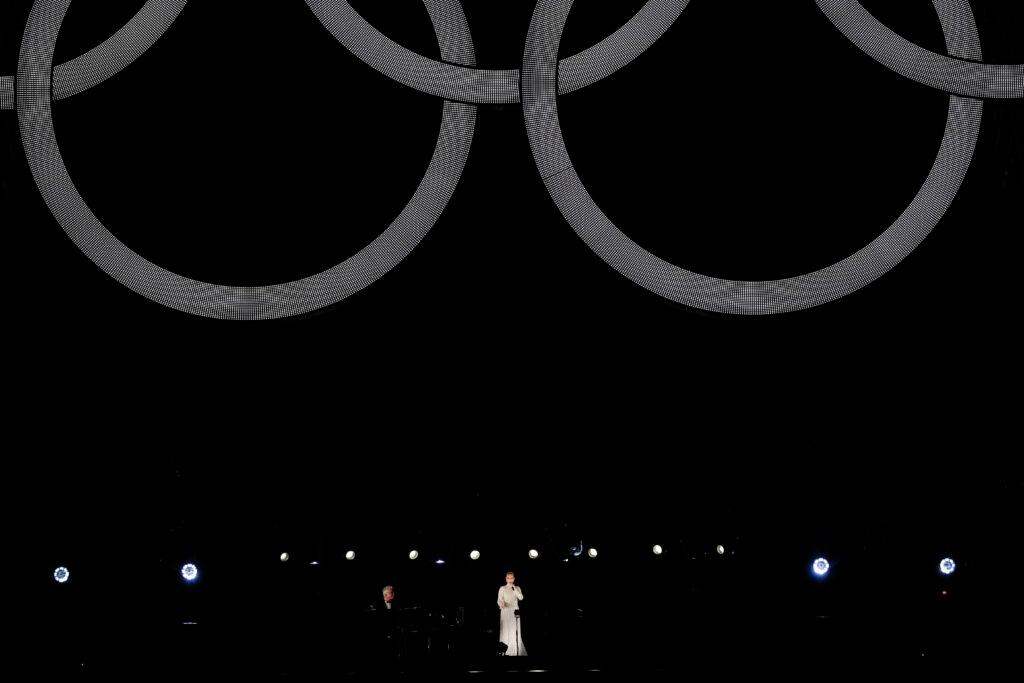

To help open the Paris Olympics, five-time Grammy winner Céline Dion delivered an electrifying rendition of Édith Piaf’s, “Hymne à l'amour.” The performance is all the more gripping in light of Dion’s battle with stiff person syndrome (SPS). That battle is documented in the new film, “I Am: Céline Dion,” which shows the singer, at times, immobilized and unable to utter more than a cry for help.

In hopes of helping others with this autoimmune disease, the Celine Dion Foundation has given $2 million to the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus. The money endows a chair in autoimmune neurology.

Dr. Amanda Piquet, the inaugural chair, spoke with Colorado Matters host Ryan Warner about the nature of this disease, which disproportionately affects women. She says it is not as rare as first believed.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity

Ryan Warner: Help us understand what people with stiff person syndrome experience.

Dr. Amanda Piquet: Stiff person syndrome is a progressive autoimmune neurologic disorder. Patients have muscle spasms and/or muscle stiffness. That stiffness can cause problems with walking, movements, including eye movements, as well as speech.

Warner: Eye movements?

Dr. Piquet: Yes. Stiff person spectrum disorder can include cerebellar problems. That's the balance center of your brain, which coordinates many different types of movements, including eye movements.

Warner: And in Céline Dion's case, it had a profound effect on her ability to sing.

Dr. Piquet: Correct. We can see that due to muscle stiffness and muscle spasms. When you think about it, it's very common to get stiffness in the trunk of the body in stiff person syndrome. So when I say ‘trunk,’ I'm talking about belly, chest, back. And if you have muscle spasms and stiffness in the chest, you can imagine it's much harder to expand that rib cage when you take a deep breath, which is clearly essential for singing.

Warner: I think it's really important that you talked about this being spectral.

Dr. Piquet: And the spectrum has evolved. It was first identified in 1956 as stiff man syndrome because it was identified in four men at the Mayo Clinic. Since then, we have learned a lot more. It is more common in women. About 60 to 70% of cases occur in women. And those muscle spasms are unique. They are often triggered by emotions, and that can be a positive or negative emotion. We can see triggers of sound, light, and anxiety. Sometimes we see with this disease something called agoraphobia, where crowds, being in a crowded space, can trigger some of these things.

Warner: I want to unpack a few of the words that you use to describe stiff person syndrome. You said it was ‘progressive,’ it was ‘autoimmune’ and ‘neurologic.’ ‘Progressive’ indicates that it gets worse over time. Yet we saw such a stunning performance from Céline Dion in contrast to what is on display in that documentary.

Dr. Piquet: Absolutely. And progressive can look different in different individuals. Studies have shown that about a third of patients– despite immune therapy– have progression. That's a decline in their walking, a decline in their neurologic function. However, I do also want to emphasize that we continuously work to find better treatments for this disease. There are patients that do well and we manage this disease. It's not a cure. We manage this disease just like diabetes, with immune therapies and treating symptoms. But it does require, just like diabetes, to go in and see your doctor on a certain interval. You're continuously tweaking those therapies to get the best function that you can get.

Warner: And then this notion that it's autoimmune. That means that it's the body attacking itself?

Dr. Piquet: Yes. You can think of autoimmune disease as a dysfunctional immune system. We often say, “Hey, the immune system's working too well, and it's fighting against itself,” but really it's a dysfunction of that immune system. And because it's dysfunctional, you can create antibodies.

Warner: So those antibodies are present in everyone who has stiff person syndrome?

Dr. Piquet: That's a great question. Not necessarily. GAD65 antibodies are the most common antibody we see with this disease. We can also see other antibodies and there are a subset of patients that are antibody-negative – probably about 20%. However, that still needs to be studied a bit further.

Warner: Gosh, it sounds so confounding!

Dr. Piquet: It is not an easy diagnosis to make. Patients go on diagnostic odysseys and can take years to get to a diagnosis because it is a challenge. It's difficult.

Warner: Did you watch the performance in Paris?

Dr. Piquet: I did. It was incredible to see. It was emotional. I am just so impressed with Céline. And I have to say, I am so impressed with all of my patients with SPS. I am just continuously surprised with what patients can endure.

Warner: A few numbers … I think Céline Dion says throughout the documentary that it's a one-in-a-million disease. Is that about right?

Dr. Piquet: That is the terminology we often coin with this disease, “one in a million.” That is not based on formal, well-done epidemiology studies. That is a bit of a guess. I have to say that it is probably more common than we recognize. Misdiagnosis is part of that. We have done a study at the University of Colorado healthcare system – so looking over the course of 10 years and then looking at how many SPS patients that we see. Looking at it that way, we are looking at one to two per 100,000.

Warner: Oh goodness. Far more common than that kind of catchphrase would indicate!

Dr. Piquet: Absolutely. A very drastic difference in terms of numbers. And I think that is for multiple reasons, misdiagnosis, like I said, particularly cases that are on that spectrum that have been missed in the past.

Warner: I wonder if some of this is about healthcare disparities, the notion that women tend not to be believed about what they're experiencing, or dismissed. Do you think that that has any part in this?

Dr. Piquet: Yeah, unfortunately, I think that does play a role. And it's not unique to SPS, but we certainly see that with more common diseases like multiple sclerosis, where patients have nonspecific symptoms. This can include anxiety, this can include fatigue, muscle spasms that come and go that are maybe unwitnessed in the clinic. It's kind of like that analogy, your car's making a funny noise and you take it to the mechanic and then you don't see anything. And I think it's very easy with these nonspecific symptoms to get dismissed. Unfortunately, I believe women are a little more prone to being dismissed as “this is just you being anxious” and told this is in their head.

Warner: One more number: Céline Dion has given $2 million to CU. Do you know how that's being used? What are the most prominent avenues of research?

Dr. Piquet: I have been honored with this incredible gift from the Céline Dion Foundation. It will be utilized as an endowed chair in autoimmune neurology. So I'm the inaugural holder of that. We are using this to bring in patients from out of state, to help them with SPS, to get to a diagnosis faster, get them on treatments. And then the second component is to advance our research. We are going to learn from all of these patients, and that information will go into our autoimmune neurologic disease registry, which is foundational to our research. We're going to learn more about stiff person syndrome, including studies of what is the underlying driver of this disease, and what that means in terms of getting treatments to patients. We are incredibly excited to be involved with a clinical trial that is projected to open at the end of the September/early October this year for a new therapy in SPS.

Warner: Is that an immunotherapy?

Dr. Piquet: It is. We are partnering with our industry colleagues at Kyverna. It is a type of therapy that's often utilized in cancer. However, there are new studies looking at this for autoimmune disease– most recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine. They looked at this particular therapy for lupus and it targets the immune system. And so it is a cell-based therapy. Basically, you're taking immune cells from the patient, modifying them, giving them back to the patient, and targeting a part of the immune system that will take it out of the picture– that we believe to be part of the driver of stiff-person syndrome, as well as other autoimmune diseases.

Warner: Awareness of a particular disease can skyrocket when a famous or a rich person is diagnosed with it. And I wonder if you feel torn or ambivalent – because there are any number of “orphan diseases” that may not yet have a champion?

Dr. Piquet: Yeah. I mean, obviously, this is a difficult neurologic disease that I would wish on nobody. It's tough, right? I don't want to see anyone suffer. But at the same time, when a public figure gets this disease, it really does bring new treatments and new opportunities. There are a lot of orphan diseases out there, like you said, that do not have that champion. And it's a shame. I see a lot of those diseases in autoimmune neurology. But like I had said before, as we get better therapies in stiff-person, hopefully, that does touch those other orphan diseases in the autoimmune space.

Warner: Do young people get stiff person syndrome?

Dr. Piquet: Typically, the average demographic is a woman, like I said, and the average age is around 50. However, there is a publication out from the Mayo Clinic that suggests about 5% of cases are in the pediatric or young adult population. I think we just need to look at that a little bit more with our epidemiology studies. And I'm sure as we learn more about the spectrum, perhaps there are cases in the pediatric world that we miss.

Warner: Do you imagine Colorado becoming a global center for this or has that already happened?

Dr. Piquet: We are on our way to that goal. My vision for the autoimmune neurology program here at the University of Colorado is to become a destination clinic for these autoimmune neurologic conditions, specifically now on stiff-person syndrome. That incredible gift from the Céline Dion Foundation is a step in moving in that direction. We have that global awareness, as well as the funding and the infrastructure to allow consultations across the country and hopefully across the globe.

Warner: What keeps you going amidst all this mystery, amidst all these questions?

Dr. Piquet: I am just so incredibly inspired by my patients and their fight against autoimmunity. I do have a family history of autoimmune disease in the family, and I'm just ... I don't know … it inspires me. That's why I fight.