At the center of one of Colorado Springs' busiest intersections, a statue of city founder General William J. Palmer saddles a horse, a nod to the city’s origins and a recurring topic of debate.

The bronze monument, placed in 1929, stands where Platte and Nevada Avenues meet. It's not just a landmark. For many, it’s a symbol of the city’s evolving conversation about history, safety, and identity.

Concerns over the statue’s impact on traffic have simmered for years, said City Traffic Engineer Todd Frisbie. A city study completed last year showed a higher-than-expected crash rate involving vehicles attempting left turns across traffic at the intersection.

The study posed two possible solutions: limit some left turns, which was implemented in 2023, or convert the intersection into a roundabout.

The city estimated that the roundabout would cost about $5.5 million, said Frisbie.

So for now, Frisbie said his department is evaluating whether limiting left turns improves crash rates.

But the debate surrounding the Palmer statue isn't just about traffic engineering

It’s about how the city remembers — and reckons with — its past.

The statue was placed intentionally after Palmer’s death, said Matt Mayberry, director of Cultural Services for the city.

“It was placed there by a vote of the electors who wanted it there at that intersection, looking southwest toward the mountains and toward the [Antlers] Hotel, which was one of his properties,” Mayberry said.

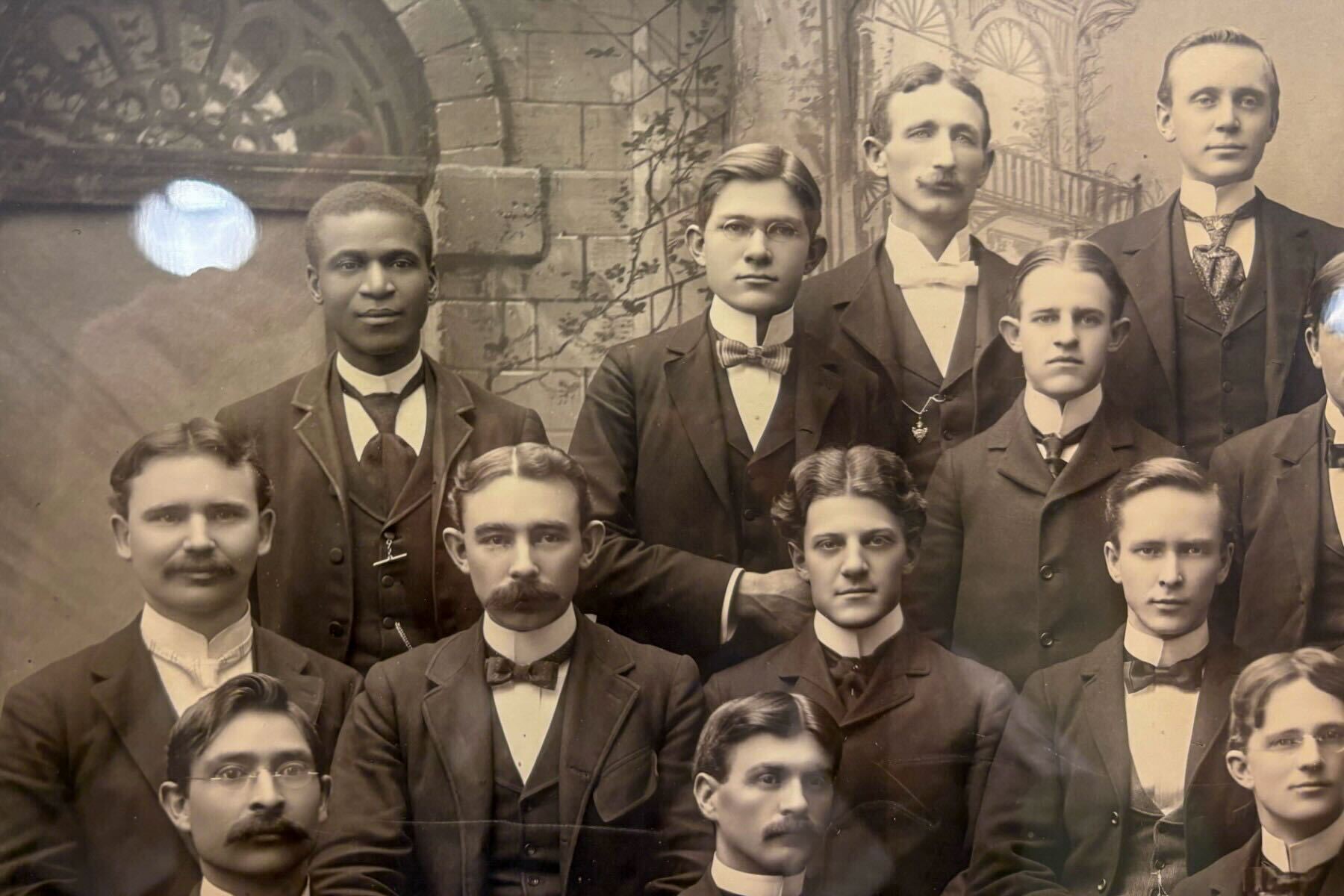

Palmer is widely credited with founding Colorado Springs and shaping its early vision.

“There aren't a lot of cities where you can point to one individual who really created the vision for the community, established the town,” Mayberry said.

Still, that framing has drawn scrutiny from residents and historians alike, particularly as public conversations evolve around who is honored in public spaces. When asked who lived in the region before Palmer, Mayberry acknowledged: “Certainly there were people here long before Palmer came here, notably the Ute, but many others.”

The statue itself also carries a lesser-known artistic legacy. It was sculpted by Nathan Potter, an artist with a notable lineage.

“Nathan Potter, who created that, is the son of the artist that created the lions outside of the New York Public Library.” While his father’s marble lions have become iconic, Nathan Potter’s bronze sculpture of General Palmer holds its own legacy as Colorado Springs’ first piece of public art, according to Mayberry.

The debate about the statue resurfaces regularly, often sparked by online discussions or renewed concerns over safety.

“It is our oldest active ever renewing controversy,” Mayberry said. “About every decade this comes up… kind of like clockwork.”

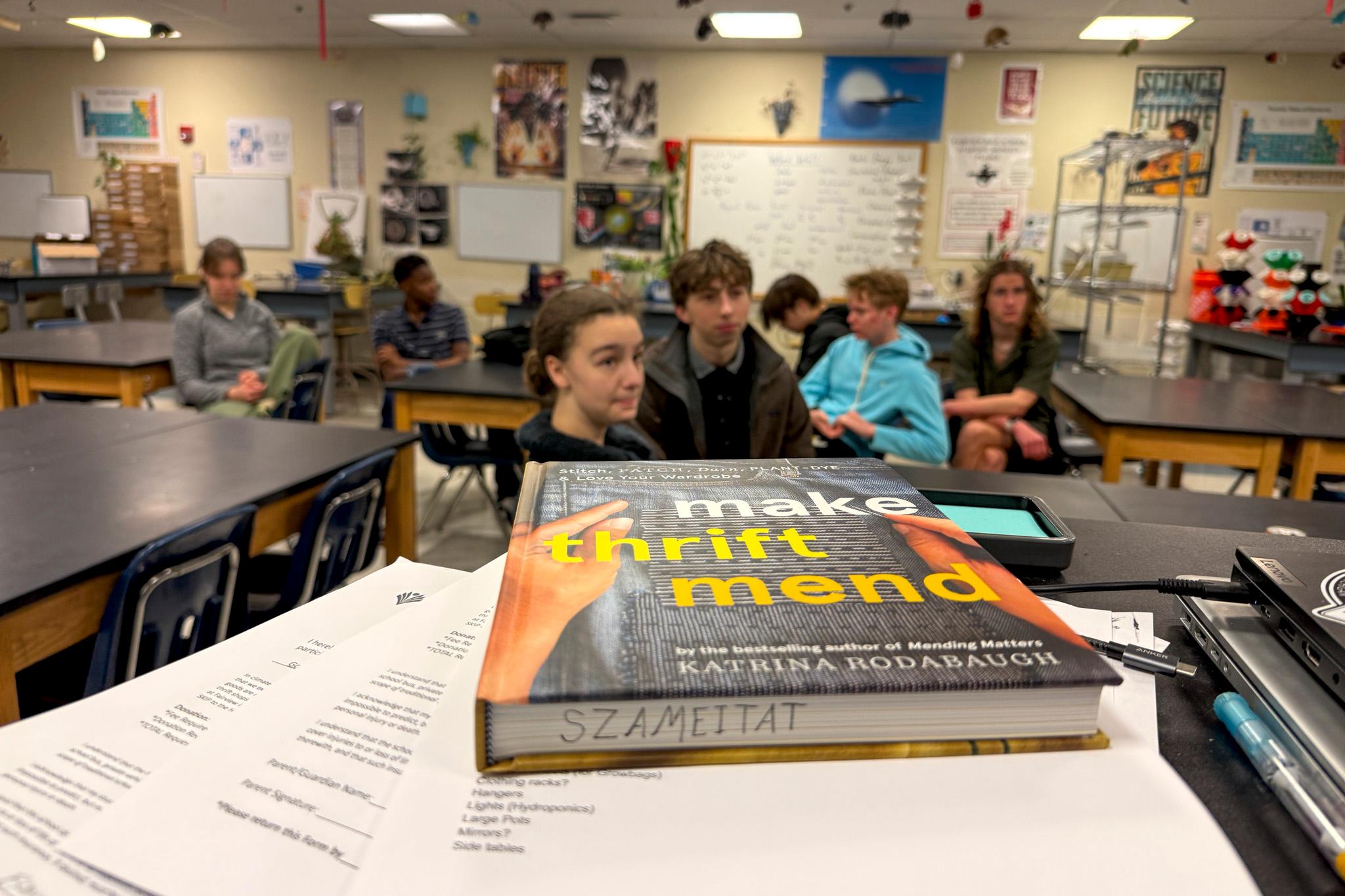

The Palmer statue, like other monuments, has become a canvas for local culture and mischief. Students from rival high schools have painted messages on the horse over the years, which the city discourages.

One myth Mayberry did bust: The horse Palmer rides is not named Diablo.

“I don't have any evidence that the horse was ever named,” he said. “It's become part of the myth that exists here in Colorado Springs.”