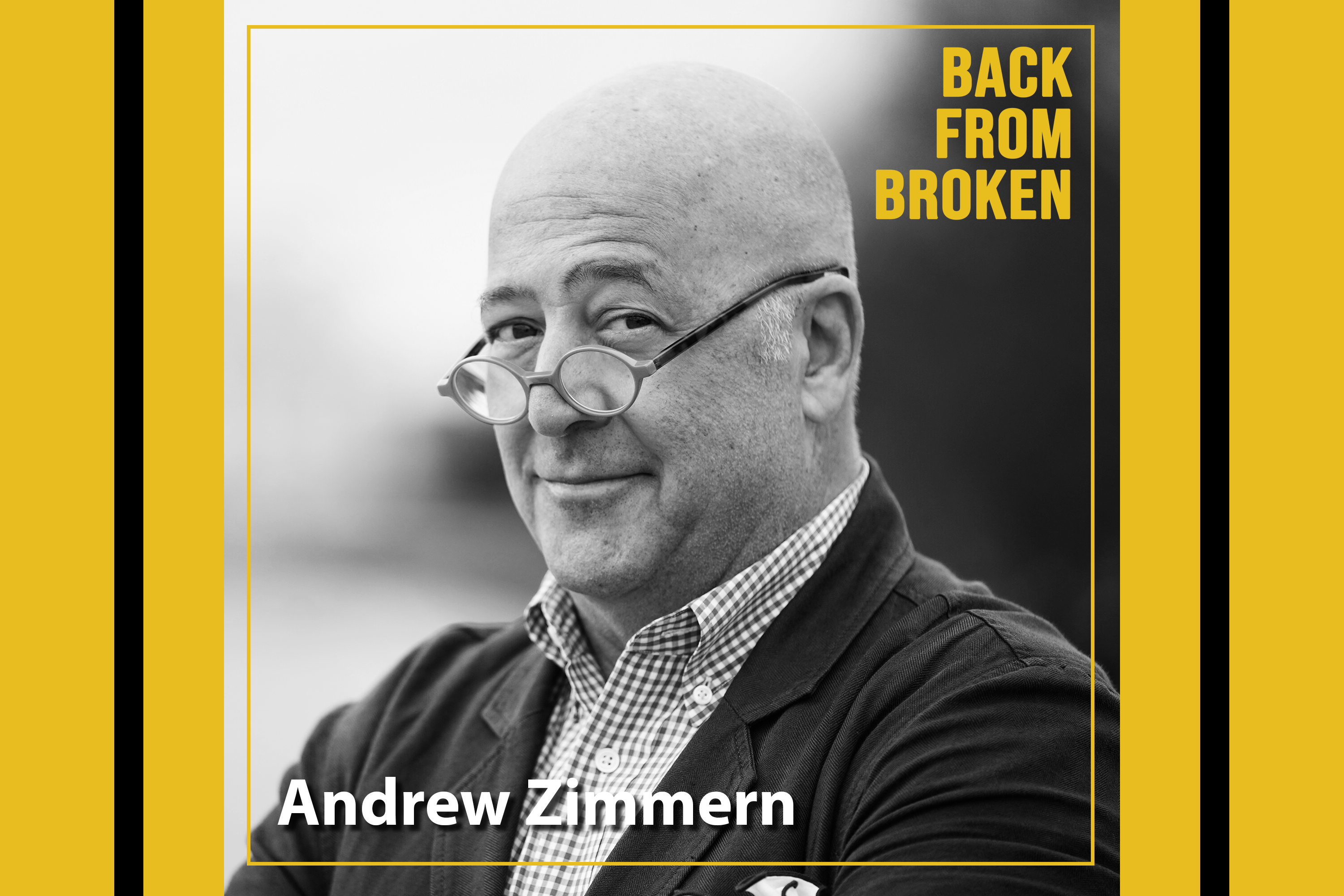

Before he became host of the shows "Bizarre Foods" and "What’s Eating America," Andrew Zimmern struggled for years with alcoholism. He was broke and desperate before he got help. Now, he's a found a way forward and he uses his work in restaurants to help others struggling with addiction.

Back from Broken is a show about how we are all broken sometimes, and how we need help from time to time. If you’re struggling, you can find a list of resources at BackFromBroken.org.

Host: Vic Vela

Lead producer: Rebekah Romberg

Editor: Dennis Funk

Producers: Luis Antonio Perez, Jo Erickson

Music: Daniel Mescher, Brad Turner

Executive Producers: Brad Turner, Rachel Estabrook

Thanks also to Hart van Denburg, Jodi Gersh, Clara Shelton, Matt Herz, Martin Skavish, Kim Nguyen, Francie Swidler.

On Twitter: @VicVela1

Transcript

Vic Vela:

Hey, it's Vic, with a quick note: This episode contains strong language and talk of suicide. Please be advised. In three, two, one…

Andrew Zimmern:

When I was like 10, I was with my mother on a vacation, down to the Caribbean, and they did one of those desserts where they pour two ounces of 151 on top of some ice cream and pineapples and light it on fire. So there was a ton of alcohol in this thing, and I remember mixing it with my ice cream and drinking it like a float. And that was the first time that I ever really remember getting drunk-drunk.

Vic Vela:

Andrew Zimmern's first encounters with alcohol were innocent enough. Before he was a celebrity chef and TV host eating stuff like fermented shark and other-worldly vegetables, he was a kid who snuck drinks here and there, often in front of older family members who thought it was more funny than serious.

Andrew Zimmern:

There were holidays where, you know, I got a glass of ginger ale and my cousins were punking me, and it was really champagne. I took a big sip and as a little kid spun around and told stories and felt the personality change from the alcohol.

Vic Vela:

For Andrew, alcohol was just a part of everyday life in a lot of ways.

Andrew Zimmern:

You know, I used to sip my dad's drinks when I made them for him, because I just loved the taste of the scotch and soda that I made for him. And I would always put the ice in the scotch in there and fill it with soda to the top of the glass so that I was forced to sip it before carrying it in so I wouldn't spill it. And that was my excuse in case I got caught, but I was addicted to the sneakiness and the lying before I was addicted to how the booze made me feel.

Vic Vela:

That early exposure to alcohol and lying and the thrill it gave Andrew was the beginning of a decades-long addiction that got worse and worse.

I'm Vic Vela. I'm a journalist, a storyteller and a recovering drug addict. And this is season two of "Back from Broken," stories about the highest highs, the darkest moments and what it takes to make a comeback.

It's a tough time right now with everything going on in the world. And then we each have our own personal struggles on top of that, but I'm really excited to welcome you back for season two of the show. And this time around, we're going to broaden the types of stories we're telling. You'll hear about PTSD and veterans issues, postpartum mental illness, the trauma of what's called gay conversion therapy, and of course, stories of addiction and recovery.

And we're starting with Andrew Zimmern who has almost 30 years of sobriety under his belt and went through hell to get there. The guy's got a lot of wisdom to share about long-term recovery. And since we are in a pandemic, we talked over our computers and I'll be honest, sometimes it sounds like it. I was at home in Denver. Andrew was in Minneapolis.

Andrew, are you there?

Andrew Zimmern:

Hello?

Vic Vela:

Hey Andrew, how's it going?

Andrew Zimmern:

Good. How are you?

Vic Vela:

I'm well, thank you so much for...

Anyway. Let me just remind everyone of why people love Andrew Zimmern.

Andrew Zimmern [audio from TV show]:

We're preparing a lawar, a traditional feast to feed about 160 people. First, the pig is blessed by a local priest and carried outside to be dispatched. The blood that's spilled will be incorporated into several of the dishes that are being prepared...

Vic Vela:

My sponsor is a big fan of yours. So before we get super serious, what's the last weird thing you ate?

Andrew Zimmern:

Last weird thing that I ate... probably this summer with my kid. We found some little crustaceans and I just pop those in my mouth just to amuse him. He still finds that interesting.

Vic Vela:

Many people know Andrew Zimmern from his show "Bizarre Foods" on the Travel Channel, where he travels around the world, eating crickets, bugs and all kinds of little critters as a way to introduce Americans to new foods and cultures. Long before his TV show, Andrew built a career as a restauranteur with a passion for food and a natural talent for cooking. And it all started in New York City, where he grew up as an only child in the 1960s and 70s. His childhood was split between his mother's and his father's homes after his parents divorced, when he was five years old.

Andrew Zimmern:

My dad had found the love of his life, which had happened to be another man, and went to live down in the West Village with my stepfather, Andre. My father had very openly told my mother about his sexuality. He really wanted a son. They were best friends and loved each other very much. And so they had a different type of marital arrangement than most other people until my father met Andre and wanted to move on with his life.

Vic Vela:

So Andrew spent most of his time with his mom, but would go to his dad's on weekends. And in the summertime, he went to camp out of state. The summer Andrew turned 13, he flew back home from camp like normal. He got off the plane expecting to see his mom. Instead, his father and his uncle were there.

Andrew Zimmern:

So I immediately knew something was up. And the two of them tried to explain to me what had happened to my mother. She had a problem during a surgery. Oxygen flow was cut off to her brain during the anesthetization process. And she was never the same. She spent years in hospitals, mental health clinics trying get right. Instead of dying, where there could be an opportunity to complete a grieving process, the mother that I knew the first 13 years of my life—she was gone and she was replaced by someone else. She had a complete personality change, hair color changed.

Vic Vela:

Well, coming back from, you know, here, you're enjoying your summer and when you go home, mom's never the same. I mean, how did that rock you?

Andrew Zimmern:

It was the most traumatic day of my life, without a doubt. We went up to the hospital room and I walked in. I saw her in an oxygen tent. And by the way, this is 1974, so we're talking about an old fashioned oxygen tent, very scary, very steam punk looking. I mean, it was just, I'll never forget it. And I just broke down hysterically.

The doctor, my uncle and my father basically told me put up your chest, stick your chin up. You've had your cry. We're going to move on. We're going to do the best we can. So we walked from the hospital, which was just eight or nine blocks away from our home in New York. And during that walk, my father reinforced all of those—and told me he would be returning downtown to his apartment with Andre. There would be a nurse and a caretaker in my home that my father had left my mother after the divorce. And I sort of became the ultimate latchkey kid.

My father continues to this day to be my hero. I have him on a pedestal. It took me 25 years into sobriety to get to the point where I could admit that that day when my father dropped me off at the apartment that he abandoned me.

Vic Vela:

Andrew, you're talking about a very difficult time in your life. You were drinking even before this happened with your mom. Did this exacerbate it? What did your drinking and drugging look like at this time?

Andrew Zimmern:

So I think it was a week or 10 days after I came home from summer camp. I made the decision to take the $200 in cash that was buried in a little envelope underneath the silverware drawer, kind of like the emergency cash in the house. And I bought a quarter pound of weed from a drug dealer that my friends and I knew in Central Park, kept some for myself, sold the rest to my buddies, put the $200 back in the envelope and was so proud of myself. I had completed my first drug deal. I'm 13 years old and I'm drinking and smoking pot. By the time I got to college, I was already a daily cocaine user, daily pill user, daily drinker, daily marijuana smoker, and had already tried heroin my senior year in high school. So by the time I got to college, I had to go see a drug counselor who took a look at me and said, "You're a chronic alcoholic and drug addict, and you're only 18 years old."

Vic Vela:

Was that the first person who ever said that to you?

Andrew Zimmern:

First one, and of course I told him to go f--- himself. Only because at that age, I'm invincible, I'm Superman.

By the end of that semester, I was asked to take second semester freshman year off by the school. I went to Europe and cooked for six months. You know, I did what I wanted to do when I wanted to do it. I mean, king baby to the max, but there was no admission that there was a problem.

As an addict and alcoholic, we go from the place where we don't know we have a problem to the next place where we know we have a problem, but we're going to lie to someone when confronted about it. And then we go to that third place where we tell someone, screw you. I don't care. In other words, we don't deny it. We almost embrace it because we know that's who we are. And that's where addicts and alcoholics go to die is at that point.

Vic Vela:

Andrew stayed at that place for a long time before he realized he truly had a problem.

Andrew Zimmern:

I didn't get sober until I was 30. So there were 12 more years of just going down, down, down, down, down, down, down. And it was horrific.

Vic Vela:

Those 12 years are filled with some of Andrew's most painful memories. Early on, he says he was living a double life. During work hours, he built his career as a successful chef, but when he was off the clock, his alcohol and drug use escalated. For a while, he was a poster child for a functioning addict, someone who is addicted to drugs, but somehow manages to show up to work and things like that. But eventually all of Andrew's money went to feeding his addiction, and he says he just couldn't keep up the façade anymore.

Andrew Zimmern:

When I finally got caught by life, when everything sort of sped up and met me at the point that I was at, when things got real, and there was no one else to talk to, no one else would lend me a dollar, no one else would let me sleep on the couch, no one else, no one else, no one else. I was sleeping in an abandoned building with a bottle gang down on Sullivan Street, an ugly, wind-blown, abandoned part of the city. I lived there somewhere around 10, 11 months. My needs weren't great. I needed what limited food I could muster, whatever limited monies I needed for alcohol. And I didn't shower. I would steal bottles of Comet cleanser to sprinkle it around the dirty pile of clothes that I slept on every night. So the rats and roaches wouldn't cross over me when I passed out. It was bad. And at that point I was doing spot jobs, stealing from my mother, hiding from my friends. No one would talk to me. I was essentially off on my own at that point with no relationships.

I would park myself outside of nightclubs. And I would watch to see if a guy in a really expensive suit left on his own, stumbling. And that became my mark. And then I would follow that person, push them down on the ground, reach into their pants, grab their wallet and run. So that was kind of an easy thing to do.

Vic Vela:

How often would you do that?

Andrew Zimmern:

Ah, once a month.

Vic Vela:

Okay. So what was that pain like? Andrew, the first time I stole what—when I started stealing to feed my addiction, I was so numb and I knew that as soon as I got my drugs, it would make everything go away, any bad things go away. It wasn't until I woke up the next morning, when I would say, "Oh my God, I stole from someone yesterday."

Andrew Zimmern:

Yeah. Yep. And that's when I would reach for whatever I had left by my bed when I passed out and take a couple of swigs so that I couldn't feel those feelings of guilt and shame.

And no matter how much I talk about it, it feels now like it was a whole other person. I just can't imagine doing that today. It's beyond my comprehension. And yet I did it. And the reason that I did was that I believed with every ounce of my being, I did not have a choice. There was no choice. I had to do it.

Vic Vela:

How Andrew made a different choice after a quick break.

After decades of drinking and using heavy drugs, Andrew finally hit rock bottom. He was barely scraping by, had few friends left. And his health was really getting bad. Feeling like he had nothing left to live for, he made a plan to end it all. It started with breaking into his godparents home in a swanky spot in the city. Andrew knew the doorman, so getting inside was easy. He stole jewelry and sold it for some extra spending money. Then he went to a hotel in a very different part of town called the San Pedro.

Andrew Zimmern:

No one checks into a hotel like that. You don't register at a hotel like that. You walk up, there's someone behind plexiglass, and you make a deal to get a room. I went upstairs. There was a phone in the room. So I did what I always do, which is just take the phone cord out of the wall. And then I walked across the street. There was a liquor store. Bought two cases of Popov vodka. And so I brought it over to the hotel. I just started drinking around the clock. I mean, chugging drinking around the clock. My goal was—I knew that I was very sick physically and I was convinced that it would be really easy to drink myself to death.

I don't know whether it was day three or four. I came to, and I wasn't dead. And for the first time since I was eight or nine years old, I did not feel the ACE bandage of pressure around my chest that I woke up with every morning of my life.

Vic Vela:

Wow.

Andrew Zimmern:

I cannot explain it. I don't know why. Even when I talk about it, when I mention it, I can feel that tension across my chest. It's like eight winds of an ACE bandage around your chest. You just feel tight. That anxiety and fear that morning was not there.

I plugged the phone back in the wall. I called my friend Clark, who I felt was the one that would not only—he was really responsible and I knew he would answer the phone call. And I knew that I'd be able to talk to him. He was stunned to hear from me. My friends thought I was dead, disappeared, gone off to Timbuktu, whatever. And he said, "Where are you?" And I told him, and I said, "Can you come get me? I need help." It was the first time I'd ever asked for help. I mean, I can't remember though, I mean, maybe since I was a kid. Wow. And he said, sure, like 20 minutes later, he was there. And he checked me out of there and took me back to his apartment. And my deal was, I wouldn't drink while I was there.

Anyway, he dropped me at his house, got me showered up. Then he went back to work to grab his stuff before coming home. We were going to have dinner together. I cased the apartment right away. I found the jar of change. I took his whole jar of change. It was like 20 bucks. So I drank all of the booze in there, the first 24 hours. I bought more booze with all the change. The reason he allowed me to do it—I didn't realize it at the time. I thought I had outsmarted him. He was already on the phone with the people at a treatment center in Minnesota, and with five or six other friends saying, "I found him, he's at the house." And the third day he's like, "Pamela wants to see you." Now I had worked for my friend Pamela's father. At one point, he owned a bunch of restaurants in New York. And I'm like, "What about?" He goes, "I don't know. I think a job." So I walked into a restaurant to meet her thinking, Oh, this is great. Clark's behind me. I'm going to get a job. This is all working out just according to plan. I walked in and there were, you know, 20 people I knew. I knew an intervention when I saw one.

Vic Vela:

The trap was set.

Andrew Zimmern:

I walked in, saw everybody. And I just looked at them. I said, "What time is my plane?" And yeah, they laughed.

Vic Vela:

So Andrew went to rehab. His friends got him into an inpatient facility in Minnesota. He met with a counselor every day, worked the 12 steps, went to meetings and listened to guest speakers. And for the most part, he really soaked it in. A clean bed and three consistent meals a day was definitely a step up from the life he had been living in New York, but recovery is not easy. And there came a time when Andrew started to get really frustrated with how he was progressing. You see, 12-step programs put a lot of focus on connection with a higher power, something bigger than yourself. Andrew noticed that other people at rehab seemed to be getting it. They were having those spiritual moments, but Andrew felt hopeless, because it just didn't click for him yet. Until one day when he was eating lunch with his friends, Cardi and Chuck, two older men in recovery, who Andrew often went to for advice.

Andrew Zimmern:

Cardi said something to me that changed my life. In every room they have the 12 steps written and he said, "Why do you think you have to have this white light spiritual experience? Why do you think you have to have a faint, light, spiritual experience? Why do you think it has to come to you?" And I just looked at him. I said, "What do you mean?" And Cardi was one of the smartest people I've ever met. And he said, "Well, you know, if you look at the 12th step." He said, "It's written in the past tense. There's a promise buried in there. And it says 'having had a spiritual experience as the result of these steps.'" And he said, "What that tells me is that there is a blocking and tackling. There is a one-foot-in-front-of-the-other, go through these steps and then you will have the spiritual experience." And I just, I literally—not figuratively—literally my jaw was in my lap. I mean, it was like the cobwebs faded. It was like the iceberg melting. It wasn't fireworks, but it was like, it was a holy moment. And it changed the direction of my life.

I went back to the unit and became the guy that did everything that I was told to do.

Vic Vela:

And after decades of drinking and drugs, Andrew was now starting a new life. He finished rehab and moved to a halfway house where something happened that Andrew carried with him through his recovery.

Andrew Zimmern:

About a month after I got to the halfway house, Chuck, who is the other guy who was at that lunch table with Cardi who—you know, I kind of worshiped Chuck and Cardi, they just had this thing figured out—Chuck had gone on to long-term care at the treatment center I was in. So he came down to the halfway house after me. And he really drilled home for me this idea that it was an all or nothing program, that either I was going to do it this rigorously and 100% and not lie, like don't tell the staff that you don't smoke in your room when you have an ashtray hidden under your pillow kind of thing, like the little things matter, like it's easier if you just go in 100% and, you know, he told me a bunch of other things, just really, really helpful stuff.

One night at the halfway house, Chuck snuck out, got drunk and drove the wrong way up a down ramp on the highway and died in the car crash.

Vic Vela:

Oh no, Andrew.

Andrew Zimmern:

And I wonder all the time why I get to be here. I have a disease inside of me that will definitely kill me the moment I stop being as vigilant as I am.

Vic Vela:

That's exactly right.

Andrew Zimmern:

It's why it's so awkward when you get a thank you from someone, for volunteering for something, because just like so many other things in recovery, first and foremost, I'm doing it for me because I have a disease that will kill me. Then secondarily, the beautiful part of this is that it ends up helping other people. And then you end up doing it, after many years, you're not sure what the motivation is. Is it because I like doing things for other people? Is it because selfishly I like the way it makes me feel? I don't really care at this point. It's how I, that's how I run my life. I'm trying to act my way into right thinking. And I keep growing the number of tools in my toolkit to make sure that I don't drink again. And if I do that, if I can just not drink again, I always have a chance.

Vic Vela:

Yeah. A friend called me who's struggling. And it was a long day at work. I was exhausted and I saw the phone ring. I'm like, "Oh, I just can't handle a heavy conversation about struggling right now." But I picked up and we talked and then throughout the conversation, he said, "I'm so sorry to be a burden. I'm sorry." And I told, I would tell him every time, "You are not being a burden. Think of it like you're helping me, because me helping you is how I stay sober, me helping you is how I stay in my recovery." And then pretty soon after an hour-long conversation, everything I was feeling before, the negative thoughts about not wanting to talk, it's been a long day. Boom, it's gone. And I felt so much better.

Andrew Zimmern:

The way the universe works in my favor is that you just told me that story, and I don't believe in coincidences. I am not perfect. I make mistakes every single day. Some days I pick up the phone and some days I push the call to the next day because of my own selfishness. Right? And some days—I think this is really important for people to understand—some days, my second or third best effort is the best that I can do.

I had a guy I sponsored many, many years ago, and I really liked him, he was a good guy. Funny, smart. Every two years, I would hear about what was going on with Todd. He was sober for a while. Then he drifted away. And I got a call one day. It was his son. He had graduated college. He was 24, 25 years old. He told me that his father had died. And it was like a gut punch. I talked to his son for about a half an hour, and that night I went back into one of my old computers. And I found an email from Todd from the year before, "Hey, just reaching out. You know, if you can give me a call or connect with me, whatever, love to talk." And I never returned the email. This is not something that I'm proud of talking about. But that day I'm sure I said to myself, Oh, I'll, you know, I'll deal with that tomorrow. I'll get back with Todd. And I never did. And Todd died a year later and his son had to call me and tell me. Now I had to tell Todd's kid that his dad had reached out to me the year beforehand. And I did nothing. I told him the story. And he said, "You did everything you could to help my dad, and my dad talked about you like the only guy that ever really tried." And you know, at this point he's crying, I'm crying. I said, "But I didn't return that last..." He said, "You know something? There were lots of other people my dad probably reached out to and someone reached out, my dad still rejected that." He said, "You could have reached out to him"—and this is a 25 year old kid who just has, you know, maybe he's gone to a couple Al-Anon meetings, right? I mean, who's sitting there saving my ass, as I'm spiraling into a shame hole. And the fact of the matter is: Yeah. I didn't have my best effort available that day. And at the same time, it's not how the universe works. I'm still working just as hard now on my recovery, I hope, as I did when I first started, and it is still no matter how long you have, no matter what happens to you, it is still progress, not perfection. Still progress, not perfection.

Because the minute we get into that perfection mode, we're setting ourselves up for a real big disappointment.

Vic Vela:

We need to, we need to give ourselves a break. We need to have compassion for ourselves. And I think that's so important. I think so many people, Andrew, what you just said there about "It's okay if we're not perfect." So many people in recovery, I think, will get that message. And I certainly do.

Let me ask you, nowadays, does your love for food provide any sort of meditation quality for you? Like is there a recovery component involved when you're cooking or talking about food?

Andrew Zimmern:

Beyond—that's the understatement of the century. Working with food has become my yoga. When I took over a restaurant at seven months sober, I made sure I was the first one in the door. Every day. I butchered all the fish. I made the soup for the day and those were my yogas at the time. No one else was in the building at that point. It was a very, very calming, meditative way to start the day. And forget about the connection to food, the meditative aspect of working with food, just the act of cooking by yourself and the focus that's required on it. You can't think about your problems or your resentments or your angers and frustrations, your jealousies, your fears. The brain is incapable of thinking about those things while you're butchering a piece of fish, because the brain protects your hands from cutting themselves, right?

And even today, Sundays are my day to cook at home. My next anniversary is in January. So we're coming up on my 29th anniversary and I'm head, ass and overcoat into recovery in the sense that, you know, I'm very active in a 12-step group. I do a lot of service work. I continue to work and rework and work and rework my recovery. I go away every year for workshops in different places to keep building on my emotional recovery. So I'm very active and I still need to decompress every night by cooking something when I come home from work. I still need to devote time on the weekends just to kind of process out my week. And I mean, for me, I do it with food. Other people do it with sports or working out or art.

Vic Vela:

Well, I can relate to a lot of that. Yeah. I can relate to a lot of that because first of all, I throw the baseball around all the time. And then as a news anchor, I'm on the air first thing in the morning. And I'm trying to write copy five minutes before I go on the air. There ain't no time for the negative thoughts to go through.

Andrew Zimmern:

That's right.

But what I really have to offer these days is for anyone in longer-term recovery, you know, 10 years+, don't stop doing what you're doing. There are so many that step away from whatever their program is. And then they wonder why, 10 years later, they pick up a drink or a drug and they're right back where they started from. And I can tell you: stay close to recovery, put recovery first and foremost into your life on a daily basis.

Vic Vela:

After 22 seasons of eating bizarre foods, Andrew Zimmern continues to host shows about food and culture. He's now the host of "What's Eating America" on MSNBC, and he continues to be an active part of the Minneapolis recovery community.